The historian John Hamer wrote a post at By Common Consent about the early Latter-day Saint Apostle Thomas B. Marsh back on July 1, 2009 . The post is titled "The Milk & Strippings Story, Thomas B. Marsh, and Brigham Young." Today’s Sunday School lesson focused, in part, on the Thomas B. Marsh cream fable (I like Hamer’s use of "fable").

Here is a selection from John’s BCC post:

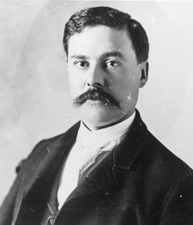

Thomas B. Marsh and his wife Elizabeth were baptized on September 3, 1830, and were therefore among the earliest members of the church. (Dan Vogel calculates that they were the 55th and 56th members, preceding all the future apostles save for William Smith and the Pratt brothers).[1] Marsh became an important early church leader and when the Council of the Twelve was organized in 1835, he was called to be one of the original members. Because he was the oldest original apostle, he became the quorum’s first president. And yet today, among Mormons, Thomas B. Marsh (if he is remembered at all) is remembered only in a story where his wife was jealous over the division of some “milk and strippings,” the fallout of which led the couple into apostasy.

History is somewhat different than the fable. Marsh was loyal to Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon in the crises of 1837, which saw the collapse of the church in Kirtland, and Marsh led efforts to expel potential troublemakers (Oliver Cowdery and the Whitmers) from their leadership roles in the church in Missouri. However, just a few months later, during the events of the 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, Marsh did voluntarily leave the faith, (along with fellow apostle Orson Hyde who soon returned). As Marsh explained in his October 24, 1838,affidavit, he left because he was alarmed that his fellow coreligionists had formed mobs, expelled all the non-Mormons from Daviess County, stolen their property, and burned their homes and towns to the ground.

Although the Mormons at the time were steeped in Gideon’s mythic defeat of the Midianites (Judges 7-8), where God required only 300 men to defeat 120,000, the danger in escalating the violence — in fighting mobs with mobs and in answering pillaging with pillaging — was extreme. The Mormons were as hopelessly outnumbered as Gideon. As much as the Saints eventually suffered after their defeat, even worse results were quite possible. The massacre at Haun’s Mill might just as easily have been replicated en masse at Far West, and the trial of Joseph Smith and other leaders may well have been a court martial and summary execution, (however illegal).

Whether or not one agrees with Marsh’s conviction that the acts committed by the Saints in northwestern Missouri were immoral and impious [2], I think we can at least agree that this seed of his apostasy from the faith was no small thing. Rather, it was a big thing. Thus, while the moral the Thomas B. Marsh fable, i.e., that faith can be shattered over something inconsequential, is true enough, it would probably make sense to tell a different, more appropriate fable to illustrate that moral.

John goes on to discuss some of the theological complications of how we use the story of Thomas B. Marsh. Find the entire post here. The way Brigham Young "welcomes" Marsh back to the Church…well…caused me to shake my head.

People live complicated and nuanced lives. Thomas B. Marsh clearly did. Since reading John’s post four years ago, I have been more cautious when hearing narratives which paint others in a negative light. There is always more to the story. I would hope that others do the same to me.