In his magisterial 2007 tome A Secular Age, Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor might’ve spoken too soon. Taylor told a multi-causal story of a world increasingly drained of religious sentiment, closely connected to the emergence of a “buffered self” impervious to the metaphysical forces of the earlier “enchanted” world. But thirteen years on, the world looks rather different than Taylor perhaps predicted. An ascendant populism, frequently associated with expressions of overt faith and embrace of premodern tradition, has spread across the West. Public discourse—particularly online—now reflects fierce conflicts over issues of existential meaning and purpose.

In his magisterial 2007 tome A Secular Age, Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor might’ve spoken too soon. Taylor told a multi-causal story of a world increasingly drained of religious sentiment, closely connected to the emergence of a “buffered self” impervious to the metaphysical forces of the earlier “enchanted” world. But thirteen years on, the world looks rather different than Taylor perhaps predicted. An ascendant populism, frequently associated with expressions of overt faith and embrace of premodern tradition, has spread across the West. Public discourse—particularly online—now reflects fierce conflicts over issues of existential meaning and purpose.

Steven Smith’s 2018 volume Pagans and Christians In the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the Potomac set out to explain this turn. Centrally, Smith pointed to the developing eclipse of Christianity’s “transcendent sacred” by the pre-Christian “immanent sacred.” The more “pagan” idea of the immanent sacred, Smith argued, reflects human beings’ primal impulse to locate divinity or absolute value within the world itself, rather than in some source beyond it. For the ancient Romans, intense moments of this-worldly sensation—whether in gladiatorial games honoring Mars, intoxicating Bacchanals, or the orgasmic rites of Venus—were genuine encounters with the principles of deity. And according to Smith, that tendency has resurged in recent years. The intensity of contemporary arguments over sexual morality, among other issues, reflects an increasing willingness to treat the apex of personal experience within the world as the locus of absolute moral concern.

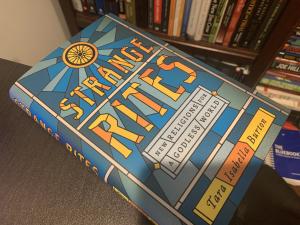

But beyond the courtroom, Smith had little to say about how this immanent sacred might appear under its cultic—that is, its more structured or ritualistic—aspects. And that is where Tara Isabella Burton’s new book Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World comes in.

Strange Rites explores and analyzes seven different movements in contemporary modern American life, all of which function—at some level—as new faith systems after the decline of mainline Protestantism. The current age, for Burton, is decidedly not secular. Rather, it has simply witnessed the collapse of institutional spirituality and the ascendance of an “intuitional religion” that allows the adherent to pick and choose the elements of their bespoke worldview.

Burton begins her argument by discussing four niche communities that fulfill a role akin to religion in the lives of their members: fandom culture, wellness culture, Wicca and neopaganism, and kink culture. Online fanfiction and Tumblr communities have democratized the interpretation and transformation of original texts that, in some sense, are treated as “sacred” because they are constitutive of the communities themselves. So too, a SoulCycle gym in suburban Virginia, a Herbalife presentation in Florida, and a BDSM club in Greenwich Village all share certain “religious” features in common— ritualistic structure, an experience of unity, and an (admittedly inchoate) concept of redemption or salvation.

But as fascinating as these observations are, they are but precursors to the book’s centerpiece: Burton’s extended treatment, in the latter half of Strange Rites, of the genuinely dominant post-Christian faith traditions in America. Two leading contenders for the crown include what Burton describes as the “Californian ideology” and the “social justice movement”—a better term than most to describe the currently prominent form of identity-oriented progressivism.

By “Californian ideology,” Burton means the combination of personal asceticism and secular millenarianism that appears to be prominent among the leadership of Silicon Valley—Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and others. This ideology asserts that science, not divinity, ultimately offers answers to the deep anxieties of the human experience. And to that end, its wealthy proponents have attempted to solve the problem of mortality through cryopreservation—deep-freezing one’s corpse in anticipation of the eventual possibility of biological resurrection—and mechanisms for uploading the contents of the human mind to computer systems. Philosophically speaking, the Californian Ideology draws on a mélange of Stoicism, Zen Buddhism, and Eliezer Yudkowsky’s large-R Rationality—an approach to metacognition intended to eradicate the prejudices and biases endemic to conscious thought.

The Californian Ideology undeniably carries with it a set of implicit political commitments, which manifest in reality as a sort of left-libertarianism. Freedom from regulation and higher authority is a necessary precondition, of course, for the endless techno-Darwinian cycles of disruption and transformation so foundational to Silicon Valley’s business model.

To be sure, this acquisitive, dog-eat-dog worldview is not without its spiritual rivals—most notably, the emerging social justice movement so visible on the internet. Burton is certainly not the first to comment on the “religious” dimensions of the modern social justice movement—as seemingly far back as 2017, New York columnist Andrew Sullivan wondered “Is Intersectionality a Religion?” The familiar rhythm of online call-outs and apologies has an overtly confessional structure to it, and activists increasingly deploy an ever-evolving vocabulary, filled with words like neutrois and demiboy and aromantic, that rivals any scholastic theology in terms of sheer arcane complexity.

Burton takes the movement’s religious structure quite seriously, arguing that the system offers substantially more explanatory power than many of its critics allow. For the activist committed to radical social transformation, every feature of civilization reflects some choice made by the holders of institutional authority, a choice that inevitably excludes those denied their say. Conventional historical narratives are always masks behind which power plays unfold. Once those plays are exposed and rejected, and all false binaries and oppositions are cast aside, true peace can finally emerge. The unity and far-reaching scope of this paradigm, Burton suggests, help account for its appeal.

Yet whether this movement can remain cohesive over time is, of course, an open question—particularly given what Burton identifies as the tension between the social justice movement’s soteriology (that is, its story of salvation) and its anthropology. For the activist, “salvation” is typically conceived as emancipation of the inner self to flourish, and destroying oppressive structures is a necessary part of attaining that ultimate end. None of us is free until all of us are free, as the saying goes. But, Burton argues, this optimism is hard to square with the movement’s anthropology—an anthropology that holds that the self is purely socially constructed, a pure product of its history and environment that can never move beyond the patterns (usually, tendencies toward oppression) that it has internalized. As Judith Butler might phrase it, the self is nothing more than the acts it performs.

How might one reconcile these competing doctrines? The answer is, at present, unclear. Internal tensions aside, though, it is likely some form of this movement—given how deeply it has embedded itself in American institutions— will persist for some time. And it is equally likely that the social justice movement will clash with the Californian ideology.

For more careful observers of modernity’s intellectual trajectory, this showdown was long in the making. In 1994, Alasdair MacIntyre published Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry: Encyclopaedia, Genealogy, Tradition—the third volume of his “Virtue Trilogy,” and an extended taxonomy and analysis of three competing contemporary modes of intellectual investigation. By encyclopaedia, MacIntyre meant the Enlightenment-rooted effort to construct a form of universal secular knowledge through unfettered application of the scientific method. The goal of inquiry, on this view, is simply the classification of the data of human experience into encyclopedic systems of structured information, essentially unmediated by individual preconceptions or biases.

The genealogy approach resists the assumptions of this “encyclopedic” model, instead focusing on how the construction and presentation of information inevitably entail value judgments. The process of inquiry involves attempts to destabilize or deconstruct, via critical theory, the engrained metaphysical presuppositions upon which all systems of structured knowledge rest. MacIntyre associates this approach with the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze, and their successors.

Finally, tradition is MacIntyre’s answer to the failings of encyclopaedia and genealogy. A healthy approach to tradition, for MacIntyre, requires the acknowledgement that human inquiry is always inevitably shaped by factors and dynamics inherited from others. There is no possible view from nowhere, as the “encyclopedic” approach asserts. But unlike genealogy, tradition entails ongoing commitment to the possibility of accessible—albeit tradition-mediated—truth beyond the self. This commitment is, essentially, faith in the reality of genuine transcendence.

The Californian Ideology and the social justice movement map almost seamlessly onto MacIntyre’s concepts of encyclopaedia and genealogy. The Californian Ideology seeks to identify and apply neutral rational principles, in accordance with the scientific method, in pursuit of objective facts; the social justice movement critiques the possibility of “neutral rationality” in the first place and unmasks such pretenses as covers for oppression. And as for tradition? That is the domain of the transcendent sacred, which latter-day seekers of immanent divinity have long since abandoned. What Smith labels “paganism” is, for many, the only game in town.

But, Burton notes, there is a fourth philosophical contestant in the mix now. And this contestant is one that even MacIntyre never foresaw.

In recent years, the darker places of the internet have brought forth a worldview that is simultaneously novel and ancient. Exemplified by the bestselling ebook Bronze Age Mindset, penned by a pseudonymous author known only as “Bronze Age Pervert,” this throwback philosophy glorifies physical strength, sexual domination, and the endless struggle for survival. Modernity, on this view, has grown decadent and failed because it has forgotten the vital principles of the pre-Christian order. Naturally, such a worldview centers the concepts of kin, tribe, and race—making it a perfect philosophy for the racist alt-right.

Other examples of this belief system, Burton points out, are legion. There are the Reddit communities where “incels” (involuntarily celibate people) fume at the sexually successful “Chads” and “Staceys” of the world. There is Jordan Peterson, reaching millions of young men with his curious blend of Jungian psychology and biological determinism. There are the meme factories of 4chan and 8chan, churning out vast amounts of race-baiting propaganda in support of Donald Trump’s presidential bid. And while many of these would be horrified at being grouped together under one conceptual umbrella, Burton identifies a common philosophical foundation among them: the overwhelming need to get in touch with the primordial impulses and concerns of the premodern past.

This is what Burton calls atavism, a secular faith “at once nostalgic and nihilistic.” Viewed in the context of MacIntyre’s threefold scheme of encyclopaedia, genealogy, and tradition, atavism directly attacks the presupposition underlying MacIntyre’s trifecta: that inquiry as such is an activity in which humans properly ought to engage. Both genealogy and atavism are heirs of Nietzsche, but where the former promises an emancipatory nihilism—absolute liberation from external constraint as a form of self-extinction—the latter offers only a nihilism of violence and disruption. For the atavist, the answer to the question what is best in life was compellingly answered by Conan the Barbarian: to drive your enemies before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women.

Thus, the battle lines of contemporary religious conflict are drawn. The next several years will reflect a three-way war between worshipers of the immanent sacred as encyclopaedia, genealogy, and atavism contend for the future. Which will prevail? That is the closing question Burton leaves the reader to contemplate.

But equally important, it seems to me, is a question Burton does not pose: can any of these new faiths actually rule?

Steven Smith explained in Pagans and Christians In the City that the tenets of classical paganism were closely bound up with the need to enforce civic order: being a good Roman meant faithfully honoring the emperor, the gods of culture, and the gods of nature. Deviation from this norm risked catastrophic cultural breakdown. To turn to Charles Taylor again, the premodern individual self was essentially porous to the divine, a participant in the rites and rhythms necessary to maintain the functioning of the world. This, in turn, underpinned the Roman persecution of early Christians—those who refused to burn incense to Caesar were, at bottom, destabilizing society.

A central motif in Burton’s book is the essentially self-oriented character of today’s post-Christian faiths—the intuitional religions. The California Ideology, at its worst, resembles an Ayn Rand fever dream. The social justice movement epistemically privileges subjective experience over external criteria of verifiability. And the fully actualized atavist eschews civilized society altogether in favor of his self-assertion as Übermensch. But that self-centered orientation was absent from the pre-Christian social order. Classical pagan society was oriented toward an intelligible concept of the common good, albeit a limited one: perform these rites, or the world fails. And as David Bentley Hart and Robert Louis Wilken would no doubt be happy to point out, it was Christianity—not paganism—that first ushered into the West the concept of individual human dignity.

The loss of a unifying concept of the common good, which was essential for classical paganism to “work,” is effectively the loss of that which made Greece and Rome so attractive to begin with. The combination of a philosophy centered on the self with a purely immanent sense of sacrality—that is, a denial of transcendent value—leads inexorably toward an eternally Hobbesian state of conflict, an unending war of all against all. How, after all, could any conflict be successfully resolved, save by destruction of the Other? None of the new faiths are capable of advancing a principle of the common good with the capacity to demand universal assent.

Perhaps I am wrong about that, though. History will tell.

In any case, Strange Rites is one of the best books I’ve come across all year. Burton is a journalist by profession, and Strange Rites is an uncommonly well-written book. Despite the complexity of its subject matter, the volume never gets bogged down in turgid social theory or excessive expert quotations—Burton, wielding a theology doctorate from Oxford, is the expert. There’s also a pleasantly gonzo edge to many of Burton’s anecdotes and observations: it’s clear she has not just academic, but experiential, familiarity with her subject matter.

Suffice it to say that Strange Rites should be mandatory reading for anyone seeking to understand the state of belief in America. There’s nothing else like it out there.