As a rule, I spend more than enough time on this site challenging expressions of political theology that, in some way or another, strike me as missing the mark.

As a rule, I spend more than enough time on this site challenging expressions of political theology that, in some way or another, strike me as missing the mark.

That’s because, in surveying the contemporary field of political thought, I find myself theologically and intellectually dissatisfied with the range of “ideological” options on offer. Liberalism, such as it is, paradoxically forfeits the happiness that comes from living within bounded limits, in the pursuit of an always-deferred exultation in the elimination of all constraints. Marxist traditions all too often treat the improvement of material circumstances as a comprehensive social panacea, capable of eradicating depression, suffering, and criminality in a single blow. Integralism and its variants presumptuously assume an exhaustive knowledge of God’s commands, one that denies all possibility of “uncertainty this side of heaven” and attaches an unchallengeable divine mandate to the will of a single papal sovereign. All of these systems, when absolutized, seem to suffer from profound internal vulnerabilities.

What if the answer, then, is “none of the above”?

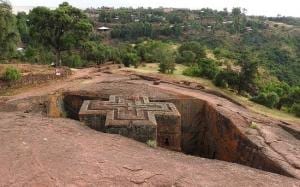

Over the last few months, I’ve been exploring the work of Ethiopian Lutheran theologian Gudina Tumsa, who was martyred by Marxist revolutionaries in 1979. Gudina’s work is fascinating for many reasons—for one thing, Gudina opposed moves by European churches to supplant mission work with secular relief funds, and outright rejected Western squeamishness about “colonialism.” (That is certainly not a story you’re likely to hear in many places.)

To my mind, though, perhaps the most helpful element of Gudina’s theology is his emphasis on the ongoing life of the church as the church during a time of political upheaval. For Gudina, since “Christ is the living Lord who was raised from death by God the Father,” and “[a] living person cannot be identified with any impersonal system,” a Christian “can work in any system, and the living Lord Christ commands us to go out and proclaim his presence, the good news.” That is straightforward enough, even if the destiny of any particular political order is not. And while there are obviously certain moral limits on the extent to which a Christian can participate in the work of a given regime, Gudina recognizes that opportunities for Christians will likely always be available at some level.

There is an element in Gudina’s work, it seems to me, that pushes beyond some of today’s intellectual impasses. The implicit assumption of much Western political theory (and, relatedly, political theology) is the theoretical possibility of regime continuity—a belief that one can design and structure institutions that, once properly configured and calibrated, can largely operate on their own indefinitely. (Even Marxism, for all its talk of revolution, posits a finally enduring communist society as the scientific culmination of history). Yet for Gudina, faced with transformative change and an uncertain future, the preservation of regime continuity was not really the point of political theology at all. The questions of political theology must instead always be posed at the level of the individual Christian.

What this suggests is that there is no single, valid-for-all-time Christian answer to the question of the “best form of government.” That question can only be answered by reference to any number of contingent circumstances. In a monarchy, is the king wise? In a democracy, are the people virtuous? Ex ante, removed from any particular circumstance, these questions are entirely unanswerable. (Even St. Thomas Aquinas admitted a degree of ambiguity on this point.) But Gudina goes beyond Aquinas (and the integralists who claim to follow him) in working out an expression of Christian faithfulness in the midst of dramatic regime change. If God’s kingdom is administered by way of two swords—temporal and spiritual—is it possible to live rightly when the former sword is blunted or broken? Gudina certainly believed so.

These cursory observations, of course, are the very farthest thing from a comprehensively worked out political theory. But they are also very far from the endless jeremiads against modernity that seem to occupy rather too much room in conservative heads. If the recent Polish example is any indication, the sociocultural clock is not turning back anytime soon. The first-order question is not a matter of one ideology against another, but rather how to live faithfully and well in a profoundly dis-integrated society.