Tara Isabella Burton, a novelist and social critic whom I always take time out of my day to read, has a fascinating essay up at Gawker about one of the strangest and most compelling novels I’ve read in the last few years: Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Tartt is best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning epic The Goldfinch—a sprawling meditation on beauty and meaning in the modern world, in the guise of an artworld thriller—but I’ve always thought that her earlier novel is substantially stronger. The Goldfinch is lush and languid; by contrast The Secret History is chilly and biting, and I find myself recalling it surprisingly often.

Tara Isabella Burton, a novelist and social critic whom I always take time out of my day to read, has a fascinating essay up at Gawker about one of the strangest and most compelling novels I’ve read in the last few years: Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Tartt is best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning epic The Goldfinch—a sprawling meditation on beauty and meaning in the modern world, in the guise of an artworld thriller—but I’ve always thought that her earlier novel is substantially stronger. The Goldfinch is lush and languid; by contrast The Secret History is chilly and biting, and I find myself recalling it surprisingly often.

I first read the novel on a business trip to Charlotte, North Carolina, tearing through pages at the hotel bar after long days defending depositions, and finally coming to its wrenching denouement on a rain-spattered redeye flight. And in many ways I think that was the perfect setting in which to read it: it takes being fully embedded within the banality of modernity in order to properly feel The Secret History’s pull.

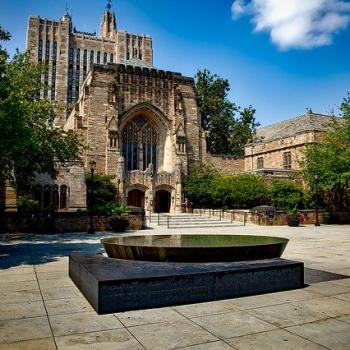

The Secret History is a “school story” set at Hampden College in rural New England, where a group of brilliant young classics students fall under the spell of a charismatic professor. Their studies of the premodern past have a transformative effect on them: over time, they grow more and more alienated from conventional moral norms and more aligned with the ancient world, culminating in their embrace of strange and bloody Dionysian rites in the surrounding woods.

Burton confesses that Tartt’s novel has always left her cold. “Tartt’s characters are, rather, moral aliens: less sociopaths than exemplars of a worldview that treats human life as simultaneously tragic and meaningless.” True. And so is Burton’s observation that within The Secret History’s starkly immanent frame, “[t]here is nothing on the other side of what we yearn for, no moral or metaphysical reality that lies beyond our grasp.” Transcendence does not exist; what is given to us within phenomenal reality is all we have.

All of this is a very fair characterization of the text. And yet the very things Burton finds off-putting are the elements that, to my mind, make The Secret History so arresting. As I see it, Tartt’s novel is a haunting—and clarifying—look at what it would look like to transpose an essentially pre-Christian moral vision into the contemporary age.

There is a persistent temptation that confronts many philosophical conservatives, who love the past and cherish traditions at risk of being forgotten, to go “back behind” what David Bentley Hart has called “the Christian interruption” in an effort to reclaim the brutal beauties of a mythic and pagan age. We only have that age available to us as mediated through the writings of great minds, but it still exerts a powerful pull nevertheless. How should that tendency inform how we think about education?

I’m reminded here of Frederick Wilhelmsen’s extended critique of “Great Books” curricula, when those curricula are divorced from a particular theological tradition and a commitment to pursuing truth over “meaning.” Wilhemsen argues persuasively that one cannot assume, a priori, that the study of classics will have a beneficial effect: expecting a student “to read all those books, to give reports on their content, but generally to refrain from personal judgment” simply defers the character formation that comes with making a truth-claim one’s own. Or in other words: what really matters is how one lives after reading great books, not the number of them one happens to have read. And Tartt’s novel is a searing illustration of the point.

But even more striking, to my mind, is a point Wilhelmsen does not develop: in many cases, the structure of this pedagogical approach is implicitly one of descent and deterioration from a Greco-Roman golden age. First came the Greeks, with the dialectic of being and becoming at the heart of Eleatic thought, with the natural hierarchies of Plato and Aristotle, with the sacred geometries of Pythagoreas and the ecstasies of the Eleusinian mysteries. Then came Christianity, which carried with it the transcendental monotheism of Judaic thought, and after that the Enlightenment. And so on down through to Nietzsche and the rise of the will to power. In a sense, this curricular approach plays out as a vindication of Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity. If the modern world has forgotten the wisdom it once possessed, then that initial forgetfulness had to occur at some point; by positioning the classical Hellenic tradition at the apex of Western thought, the paradigm suggests the primordial “wrong turn” that gave rise to modern decadence must, at the last, prove to have been the Christian turn. Indeed, as no less a conservative-aligned luminary than Leo Strauss wrote, “a genuine philosopher can never become a genuine convert to Judaism or to any other revealed religion.” (Persecution and the Art of Writing, 104–05)

And yet abandoning revelation tout court carries with it a high price. As Jewish philosopher Yehuda Halevi contended, Strauss argues, sacrificial love can find no warrant where moral judgment is untethered from divine revelation:

[N]atural morality is, strictly speaking, no morality at all: it is hardly distinguishable from the morality essential to the preservation of a gang of robbers. . . . [O]nly revelation can transform natural man into “the guardian of his city,” or, to use the language of the Bible, the guardian of his brother. (Persecution and the Art of Writing, 140)

“Natural morality,” stripped of that sacrificial love that finds its roots in revelation, is precisely what The Secret History holds up, in all its alien-ness. As Burton puts it, the novel “displays with lapidary specificity what the wisdom of Silenus looks like, played out over time.” She finds this narratively dissatisfying.

But speaking as someone whose philosophical and political sensibilities are rather more traditionalist, it’s impossible for me to read The Secret History without feeling the sting of its cautionary vision: whatever it is that we cherish in the past, we must ask ourselves whether our longings inevitably lead down this pagan road. And that is a persistently sobering thought.