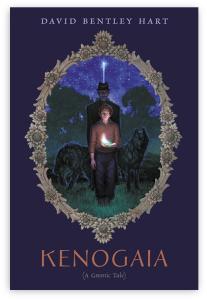

Eastern Orthodox scholar David Bentley Hart is undoubtedly best known for his comprehensively metaphysical theology and his distinctive writing style. But I don’t expect that his recent novel Kenogaia—arriving as it does from a niche publisher, without an expensive promotional campaign—will get a lot of mainstream attention. And that’s a great shame, because it’s one of Hart’s finest works (not to mention a cracking good fantasy novel).

Eastern Orthodox scholar David Bentley Hart is undoubtedly best known for his comprehensively metaphysical theology and his distinctive writing style. But I don’t expect that his recent novel Kenogaia—arriving as it does from a niche publisher, without an expensive promotional campaign—will get a lot of mainstream attention. And that’s a great shame, because it’s one of Hart’s finest works (not to mention a cracking good fantasy novel).

On its face, Kenogaia begins like almost any other YA-influenced dystopian novel. Young Michael Ambrosius, forced to live under the authoritarian regime that has kidnapped his father, witnesses the mysterious woodlands appearance of an otherworldly boy named “Oriens.” But it quickly becomes clear that Hart has the power to dramatically elevate the genre within which he’s working: once the story really kicks into gear, readers get a level of worldbuilding that puts Brandon Sanderson to shame.

Specifically, the world-picture that animates Kenogaia is what Oswald Spengler would describe as a “cavern”: a thoroughly Ptolemaic universe taking the form of concentric cosmic spheres, with stars charting fixed courses over the heads of all those dwelling within the “innermost” sphere. But what, if anything, lies outsidethe cavern, altogether beyond all the interlocking spheres of creation? That is the question of transcendence and divine light, and it is the question that drives Kenogaia.

Under threat from werewolves, shadow demons, and sorcerers, Michael and Oriens— together with their friend Laura—must undertake a dangerous journey to the capital city. There they hope to free Oriens’s sister, whose dream-energy ostensibly powers the entire structure of the cosmic spheres and keeps their inhabitants from reaching their true home beyond the stars. But the rulers of the spheres, of course, have no interest in letting this happen.

Structurally speaking, Kenogaia’s story of captivity, forgetfulness, and return to the divine draws inspiration from the Gnostic Hymn of the Pearl, an extract from the Acts of Thomas. (And indeed, Kenogaia is subtitled “A Gnostic Tale.”) And here, some clarification is likely in order.

Today, the adjective “Gnostic” is often used as a pejorative, referring to a very specific impulse: the desire to fly away from the bondage of the phenomenal world toward an otherworldly heaven. But as Hart would wish us to note, similar themes are echoed in canonical Christian texts. As Romans 8:21–22 tells us, “the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now” and human souls long to “be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God.” (KJV) Hart would likely go further than I would in characterizing the created order as principally a site of bondage, rather than as something good and yet fundamentally damaged, but the overarching point stands: what is usually called “Gnosticism” today posed such a challenge to the early Church because in many ways it shared a common conceptual vocabulary. In light of this, Kenogaia’s labeling as “A Gnostic Tale” shouldn’t be an unqualified red flag: the vision it portrays is not so much anti-Christian as pre-Christian, incomplete in the sense that a mythology can be theologically incomplete and yet still point toward a fuller truth.

Indeed, it’s this sense of incompleteness that makes Kenogaia so haunting, and its ending so elegiac. Oriens’s cosmic father and mother, a dyad of King and Queen, dwell in an inaccessible mountain palace, unavailable even to those souls emancipated from the clockwork spheres. Seemingly foreclosed forever, on this cosmology, is any prospect of knowing God “face to face.” (1 Cor. 13:12) For on a traditional Gnostic metaphysics, the highest principle can never come in contact with creation—and it took the Nicene Christian breakthrough to finally resolve this impasse. As it stands, though, a shadow of tragedy looms over Kenogaia, lending the work an unearthly beauty all its own.

In the end, I suppose that if I had to draw an analogy, I’d probably describe this novel as something like “Chronicles of Narnia meets A Series of Unfortunate Events, with a dash of BioShock.” I can’t recommend it highly enough, and I can’t wait to read it aloud to my son once he’s old enough to understand it. Books that fire the imagination like this one are in short supply.