Happy Ascension Thursday! Here in Boston we observe the feast at its proper time, allowing for a novena of days before Pentecost. Today it is most true what Saint Paul says, “In [God] we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28), for Jesus has recapitulated the whole of humanity within the starry reaches of love.

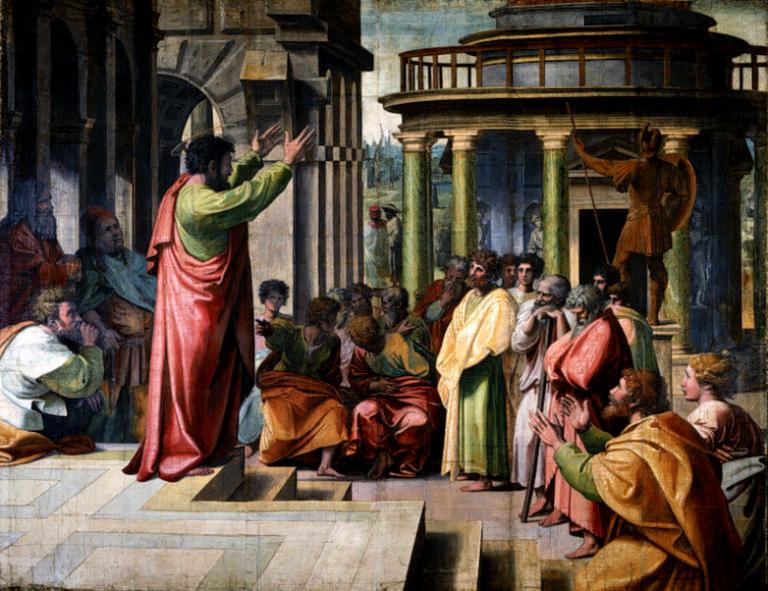

We wish to see all the nations stream towards the heights, all people in deepest communion with each other, so I want to reflect on yesterday’s first Mass reading, which presents Paul’s speech on the Areopagus in Athens, a plea for the recognition of the solidarity of all peoples under a good and gracious God, Who has revealed Himself in the vindication of Jesus.

Paul burns with the desire that every man and nation rise. What keeps us down is the lie that we are the measure of reality. When not docile to receiving revelation, we are imprisoned in idiosyncratic fantasy worlds. Common life, communion, can only exist under, and within, God.

Syncretism and idolatry provoke Paul (Acts 17:16): Athens was “full of idols.” (Idolatry will also be his first topic in addressing the other great city, at the beginning of his letter to the Romans.)

It is an epochal moment: Jewish-Christian messianic monotheism confronts the “wise” of the syncretistic capital of Greek culture (itself the ecumenical culture of the Roman Empire—compare Romans 1:16 on “Greeks”). There are materialist philosophers (Stoics and Epicureans) and polytheists both cynical and fervent in the audience, on this hill where according to Aeschylus the Furies were folded into the regime of law under Athena.

What line of reasoning does Paul pursue to captivate the Gentile or pagan or “Greek” mind? He comes across an altar “to the unknown god” and uses that as his opening: he will tell them about what they “worship without knowing.”

The goal is to convert whatever perdures of “reverence” in paganism into its truth, and to give hope to the cynical. And that requires making clear that God is the Source of every good thing and we are always beneficiaries. Paul wants to enkindle gratitude in the hearts of these men. Gratitude is piety’s path into the true religion, and we won’t recognize that we owe everything to God unless we simultaneously recognize His utter transcendence and His personal providential care.

God creates and, by direct causal contact, sustains each thing’s motion, directing all things towards a good end: “The God Who made the world and all the things in it, Who is Lord of heaven and earth, does not inhabit temples made by human hands, nor is He served by human hands, as though He needed anything, because He Himself gives to all life and breath and all” (Acts 17:24-25).

Therefore, God is not only the source of the analogical order of being, but in His personal providence, He is the master of history: “From one, He made every nation of men to inhabit the face of the whole earth, having set predetermined seasons [kairous] and the fixed boundaries of their habitations, so that they might grope for Him and might find Him, though indeed He is not far from each one of us” (vv. 26-27).

On the one hand, Paul redeems, by radicalizing, the truth of Stoic cosmopolitanism, grounding it in our shared human nature (consubstantial solidarity), in turn grounding that in the providential disposition of the Father to realize a unity of Trinitarian expansiveness. On this basis, by His sacrifice, Jesus can tear down the wall of separation between peoples (whether Jew/Gentile or Greek/barbarian), for the expansion from one and two into many (original solitude to original unity) was always intended for a universal reunion.

On the other hand, Paul does not dissolve the contours of the particular. Indeed, the universalism of the Kingdom of God can only be attained through the particularism of the nations: unity requires difference. Paul does not purchase cosmopolitanism at the cost of patriotism. National characteristics are themselves somehow instruments serving humanity’s desire to see God and God’s desire to be known by man.

Indeed, even the concrete lifecycle of a civilization, the limits and mortality of a culture (its rising, progress, and decline) is itself somehow instrumental to the human quest for God: “having set predetermined seasons and the fixed boundaries of their habitations, so that they might grope for Him….” I think this has to do with the fact that the infinite luminosity of God can only be approached through particular refractions, and only under the pressure towards earnestness that finitude and mortality can afford.

How a people is sited in space and within the currents of world history draws out different human potencies, opening new avenues into the reality of God. The point of national existence is to celebrate God according to the unique cultural vantage and strengths a certain people possesses. Needless to say, the first step is to stop with the child sacrifice. Whether America’s kairos is now passing, we do not know, but wherever we are as a nation in our cursus, the point of culture is at all times to seek the truth about God in dead earnest.

Then Paul references a decisive insight made by a couple of poets (including Aratus, also from Tarsus) to bring his oration to a climax: “For we too are [God’s] offspring.”

An idol is whatever we fashion on our own initiative, without the divine impulse: a philosophical system, a style of worship, an ultimate concern. But such a project is metaphysically incoherent: we derive from God; we must always follow His lead: “Therefore, being God’s offspring, we ought not think that the divine is like gold, or silver, or stone, an image formed by the art and inner-spiritedness of man” (v. 29).

Is man the measure? Or is God? If God is, we must listen, attentive to the truth, beauty, goodness that’s THERE, open to receiving revelation. Or we’re only talking to ourselves. To know that we are secondary, is to have faith, to stand at attention.

Paul concludes by revealing that humanity has entered a new phase: God has broken into history in Jesus. Do the peoples seek truth and justice? The eschatological day is here, time to judge between shadow and light. The Resurrection means the “times of unknowing [agnoias]” have been superseded. We need not, and should not, any longer settle for “worshipping unknowingly [agnoountes] an unknown [agnosto] God.”

Easter makes us all young again—the Ascension even more so. Every culture on earth may begin anew. Humanity has been set in vasty spaces. We are Simeon at acme, seeing a newly risen Jesus as “a light to reveal You [Father] to the nations, and the glory of Your people Israel.”

[This was originally posted a couple of years ago on my personal blog, in a modified form, under the title, “Jewgreek is greekjew,” a reference to Ulysses, in which James Joyce grapples with these questions.]