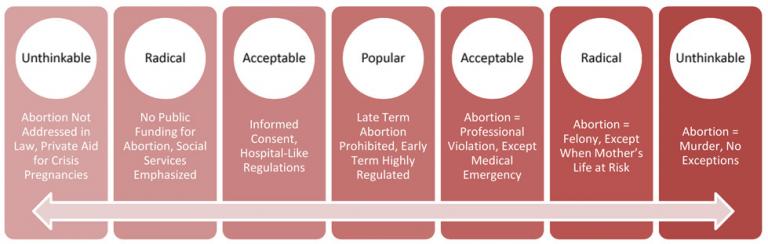

Let’s apply the Overton Window theory to the policy aims of the pro-life movement. The following spectrum provides a rough spectrum of policy aims for politically-engaged Americans who identify as pro-life, as it has seemed settled since the focus on ending “partial birth” and late term abortions became popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

This spectrum is highly influenced by the art of the possible, with the center being defined by the most abortion regulation that is possible within the confines of Roe, Casey, and Gonzales v. Carhart. It should be noted that Ohio already has some of the most restrictive (enforceable) abortion laws in the country, squarely in the “popular” spot, so some might think “mission accomplished,” at least as long as Roe remains the law of the land. The new “heartbeat bill” is an attempt to move Ohio law another step to the right—but still well within the range of acceptable for pro-life voters—and push past the bounds of Roe.

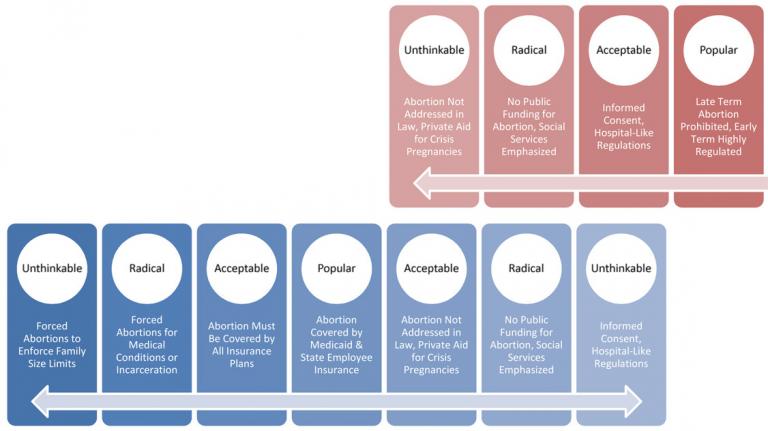

But the mainstream pro-life Overton Window only defines the “possible” where pro-life voters dominate the electorate, as they do in Ohio and some “Bible Belt” states. In states where social conservatism is not dominant, or even a distinct minority view, pro-life activists have to contend with the Overton Window of the Left, which pulls in the opposite direction. The following diagram shows how slim and tenuous the overlap of policy goals might be at the national level or in more liberal states. What is acceptable for the Left is unthinkable for the Right, and vice versa. The once-mainstream consensus—no public funding for abortions, but maintaining its legality while giving vulnerable mothers more social services to help them choose life—has become the “radical” position for both sides, as evidenced by the near-extinction of elected Democrats and Republicans who will promote such a mix of policies.

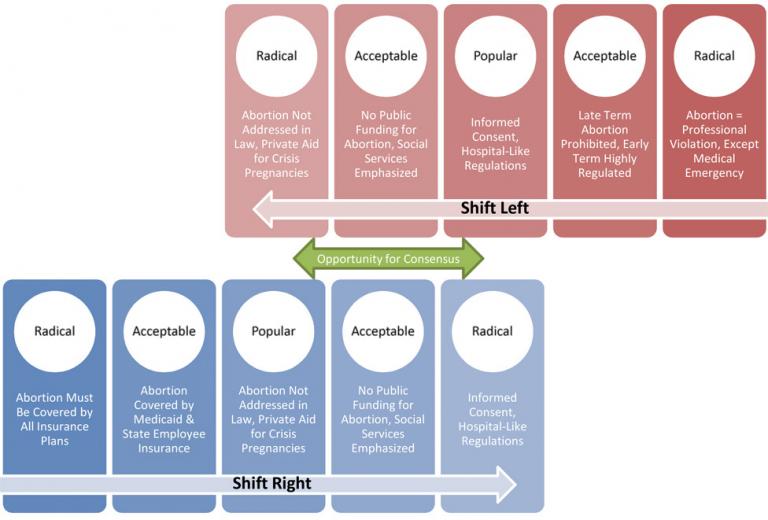

This state of affairs has contributed mightily to the toxic animosity that characterizes American politics today. With little to no space for agreement or compromise, every election is seen as an existential threat that could pull abortion policy into the realm of the unthinkable. If the goal is to establish a stable political consensus that limits and reduces abortion on demand, the rational move would be to try to shift the Overton Windows of both parties a step toward the center. As the following diagram illustrates, just a modest shift of each side toward the center would create a space for acceptable consensus and stable abortion-reducing laws. (And perhaps if the two sides did not see each other as existential threats, over time the consensus could be gradually shifted further to the right by converting hearts and minds.)

Remember, however, that politicians don’t shift the Overton Window. They occupy the acceptable space within it that has already been established by non-elected forces influencing the public. And what advocacy groups are pushing public opinion toward the center on abortion policy?

{crickets}

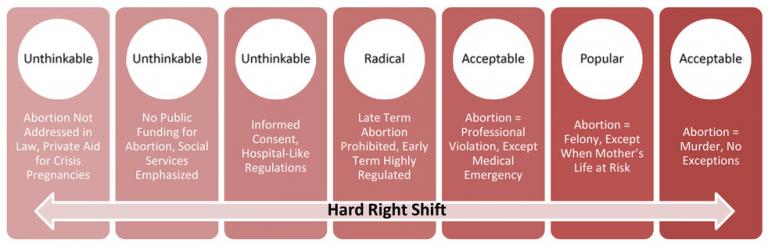

Rather, the fact that 18 members of the Ohio legislature have publicly affixed their names to possibly the most extreme, women-endangering and -punishing abortion restrictions imaginable is strong evidence that the Overton Window has already taken a hard shift to the right for an influential segment of the pro-life movement. What was unthinkable just a few years ago is now acceptable. What was acceptable among pro-life voters a few years ago is now being pushed into the realm of the unthinkable—that is, unthinkable that a person could call themselves “pro-life” and “merely” support Texas-style regulation of abortion clinics. And what was popular is now considered as radical, with the pro-life bona fides of people who “only” want to criminalize late-term abortions being sharply questioned.

This isn’t just a theoretical application of the Overton Window theory. I personally experienced this over the past two years when I got involved in the leadership of a third party that purported to be pro-life and pro-social justice. I thought, as did many party members who were involved in revising the party platform, that we would try to shift the window of acceptable policies toward the center, restricting abortion to the extent allowed by the Supreme Court, while at the same time pushing for more social services to reduce abortion demand, and explicitly rejecting the punishment of post-abortive mothers or endangerment of women’s lives. I was shocked to encounter a lot of vehement opposition to what I had always thought mainstream pro-life aims. I saw party members who explicitly called for criminal punishment of mothers, and I was repeatedly attacked as “pro-abortion” or “anti-Catholic” for taking the position that any legislation without an exception for endangerment to the life of the mother is categorically unacceptable. While there were a number of other issues at play, the faction who saw mothers’ criminal prosecution and deaths as acceptable collateral damage for the achievement of “pure” anti-abortion policy won control of the party in June 2018, at which point most of the members seeking more centrist policies quit because their views were patently unwelcome.

This radicalization of the pro-life movement’s range of acceptable policy aims is death to their actual achievement. The Irish referendum earlier this year, rejecting precisely what seems to be the new center of the American pro-life movement, demonstrates the voting public’s firm backlash against policies that can be blamed for maternal deaths and criminally penalize women, even if only in theory. And in the United States, we also need to keep the Supreme Court’s likely reactions as our foremost concern.