– George Bernard Shaw

Contents of this Article

- Introduction

- History of icons

- Divergence in Art and Practice

- Iconoclasm in the 8th and 9th Century

- The Emergence of the Modern Era

- Lutherans and icons

- Reform Churches and Icons

- Anglicans and Icons

- The Radical Reformaton and icons

- Icons in the “Modern” Catholic church

- Icons in the “Modern” Eastern church

- Bearing the image of God in a Post-Modern World

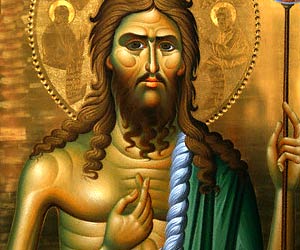

Christian worship from its earliest days reflected this tension in the way it worshiped. Physical matter was intentionally made a part of the liturgy. There was the use of bread and wine in the Eucharist, the greeting of one another with a kiss, the practice of baptising converts in water, and the use of painted icons in prayer. All of these things reflected a conviction that God’s creation was good, and Jesus’ death encompassed the whole person.

As time went on the artistic methods and subjects became more uniform throughout the church and the use of icons become widespread. Some important distinctions did arise. The church at this time began diverging artistically into three general camps: the Roman, the Byzantine, and the Coptic.

The use of icons within the Byzantine empire had gained such a level of usage by the Seventh Century that in 695 the emperor Justinian II began minting coins with the face of Jesus on one side. This move flew in the face of the Muslim empire which banned the use of images. Up to this point the Muslim world, or Ummah, had shared currency with the Byzantine Empire. After these coins were minted the Muslim Cailph, Abd al–malik, went to war with the Byzantine Empire.

The Second Council of Nicaea (787), which is believed to have the Seventh Ecumenical Council by most of the Christian world was called at this time. This council was convened to deal with the icon controversy that was dividing the church in the east. At this time Saint John of Damascus wrote in support of the use of icons. His position was ultimately the position taken by the council and can be summarised in his words from On Holy Images:

“Of old, God the incorporeal and uncircumscribed was never depicted. Now, however, when God is seen clothed in flesh, and conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter, who became matter for my sake, and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out my salvation through matter. I will not cease from honouring that matter which works my salvation. I venerate it, though not as God.”8

The modern age is an era in history that by most accounts is said to have begun around 1500 and still persists in some ways to the present day. The religious character of this era within the Christian world is greatly formed by the Protestant reformation in the West, The fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the discovery of the Americas in 1492. Out of this centers of religious power, and sources of authority were pushed into new territories.

The use of icons at this time was widespread, but varied. As we look at the use of icons around the world we must make a distinction between icons as seen in the life of the Eastern Church and icons in the west. The icons in the East had a theological and ritualistic role that was not part of the experience of the church in the West. This did not mean the church as a whole did not have a similar theology on Icons, but rather it had different forms of expression of the theology that was cemented in the Second Council of Nicea.

The differences in practice stemmed from a differences in worlds. The East and the West had developed under different political powers, using different languages, and being concerned with different goals. This divergence ultimately led to a schism between the two churches in 1054. As the forces of Modernism and Reformation challenged the authority of political powers, the role of language in worship, and the concerns of Christians in the west the way people looked at the use of Icons also changed.

As new paradigms emerged the way people began to look at the question, “why do (or don’t) you use icons in worship?” began to change. The Reformation birthed four major steams into the church: The Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, and Radical in our next few sections we will examine how these churches answered that question, and why.

The Reformation began when a German monk named Martin Luther began to publicly question the sale of indulgences within the Catholic Church. The finer theological points of what indulgences are and why Luther disagreed with them are beyond the scope of this paper. What is important is that his dissension set a series of events into play that eventually led to Luther’s excommunication from the Catholic church. Some of the German princes, inspired by Luther, or perhaps simply seeking opportunity, also separated from Rome and began looking to Luther as a guide to how the church was to move forward. This group came to be known as Lutherans, and quickly established itself as a major force within northern Europe.

At the heart of Lutheranism was a doctrine called Sola Fide or “faith alone.” After years of lecturing on Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians Luther had come to the conclusion that salvation is a gift from God that is not dependent on any deed but simply on allowing the Holy Spirit to work faith in a believer.9 This gift was made possible by Jesus’ death and Resurrection. This conviction was the nucleus out of which the rest of Lutheran Doctrine emerged.

Lutheranism has never had a strong position on icons. The most important thing was an emphasis on the Gospel we receive through faith. If images can assist in the greaching of the Gospel then they are good, if they hinder they are bad. The following quote from The Defense of the Augsburg Confession by the successor of Luther, Philip Melanthen makes this clear:

“the true adornment of the churches is godly, useful, and clear doctrine, the devout use of the Sacraments, ardent prayer, and the like. Candles, golden vessels [tapers, altar-cloths, images), and similar adornments are becoming, but they are not the adornment that properly belongs to the Church. But if the adversaries make worship consist in such matters, and not in the preaching of the Gospel, in faith, and the conflicts of faith, they are to be numbered among those whom Daniel describes as worshiping their God with gold and silver”10

The primary voices in the emergence of Reformed Protestantism were from Ulrich Zwingli and his community in Zurich, and from John Calvin and has community in Geneva. Both had a strong dislike of images which resulted in churches becoming bare walled and austere.

Ulrich Zwingli forbade the use of images believing that they took away from the glory of God.11 He looked at the Bible as the only thing that one should use to teach a Christian how to worship. In doing so all icons were supplanted for a new image, namely that of The Holy Scriptures, and Zwingli’s interpretation of them.

Calvin, like Zwingli, opposed the use of icons. He reasoned that they were a late invention and their introduction correlates to the downfall of the church he wrote in his Institutes:

“If the authority of the ancient church moves us in any way, we will recall that for about five hundred years, during which religion was still flourishing, and a pure doctrine thriving, Christian Churches were commonly empty of images. Thus, it was when the purity of the ministry had somewhat degenerated that they were first introduced for the adornment of churches.”12

If a Christian in the early reform tradition were to be asked, “Why don’t you use icons.” The answer may well be, “They are idols that presume that we can create a pretext to manifest God in this fallen world.” The emphasis in reformed theology is not Christology, or Soteriology, but Sovereignty. To sum up the reform perspective: Only God himself can create an image worthy to point to himself, and the only physical image that gives us any special revelation today is the Scriptures.

The reformation came to England when King Henry VIII broke ties with Rome over an issue over canon law that went political. Henry argued that he should be able to have his marriage annulled, the Pope at that time, Clement VII, refused. Henry went ahead and had it annulled anyways. The break that ensued between the two was total and complete, and what we know today as the Anglican communion was born. Images had been a huge part of the life of Christians in England before this split. Icons were made from wood cuts and distributed among people. People kissed these images, and received indulgences for their veneration.17

After the Church of England broke with the Church of Rome there was a good deal of stability. At first things looked, and smelled like the Catholic churches. A new prayer book was released and in its first edition it was clear that Henry VII had no intention of causing a radical reformation in any way. Since little was changed little about images was changed, in fact the use of images was explicitly encourage in the ten articles of 1536 which were the basis for the churches at that time. The first article related to ceremonies reads: “images are useful as remembrancers, but are not objects of worship.”18

Writing about the radical reformation is always difficult. The term seems to be a catch-all for any group that emerged out of the reformation that isn’t Reformed, Lutheran, or Anglican. There is no consensuses on where the radical reformation began, and certainly no common document on images held by all by which we can judge the groups.

Perhaps the best way to look at the radical reformation is as a group along a spectrum. On one side of the spectrum is the Catholic Church and as the spectrum moves along there is more and more of a desire to do away with traditional ways of worship. The Radical groups would be on the opposite side of the spectrum as the Catholics. Because of this there is a tendency to move away from icons within these groups.

One thing is common among Radical Reformers; they refuse to compromise what they believe is the call of God regardless of who was in charge. They did not believe the Church was a physical building or a temporal system, but something invisible and incorporeal. If one were to ask an early Radical reformer why they didn’t use icons in worship, they might respond, “I choose to look to that which is not passing away.” Their focus was on Eschatology.

By 1530 Catholic opponents of the reformation were recognizing and challenging the iconoclasm of the Reformed traditions. Catholic apologist Johann Eck began to attack Zwingli for his belief that images “be destroyed and burned.”24Eck said that Zwingli and those who followed this teaching “ought to be regarded as heathen and publicans.”

The irony of the reformation was that it split many churches in the West in extremes away from the Eastern understanding of images just as technology was beginning its rapid surge that would bring these two peoples into closer and closer communication with one another. For Orthodox Christians the attitude of the west was foreign, strange, and uncomfortable.

Iconoclasm was not, however, normative behavior. For the most part Eastern Christianity was Orthodox, and Orthodoxy held the Seventh Ecumenical Council in very high esteem. There is a special Divine Liturgy offered during the first Sunday in Lent called “The Triumph of Orthodoxy,” which commemorates the decision of this council. On this day a procession is made with the icons of the church which serves as a reminder of the Christological declaration made at Nicea in 787.

Bearing God’s image in a Post-Modern World

As we can see in the chart above, the theology related to icons can be a window into the core values held by a group. An Icon can be a mirror that shows us part of us that no normal mirror could hope to show. To some it reflects the image of what they hope to become. To others it reminds them of their own brokenness. To still more an icon shows beauty, and with it reminds the observer of the icon of God they were created to be. However some turn away. They are disgusted by the arrogance of the depraved soul who would seek to dare to cast an image towards a sovereign God. Others turns away from the icon because they view it as a distraction from the incorporeal reality they deeply long for.

2 Icon comes from the Greek word, εἰκών, meaning simply “image.” I will use the term icon and image somewhat interchangeably. If icons from a particular tradition are mentioned I will make sure that the place or tradition of origin is made explicit either in context or in apposition.

3 Michel Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s seminary press), 1991, 23.

4 Rachel Hachlili, Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora, Part 1 (Boston: BRILL),1998, 89

5 Canon 82, Mansi, CI, col.960

6 Michel Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s seminary press), 1991, 33-35.

7 Arnold Joseph Toynbee, A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes VII-X (Chicago: Oxford University Press), 1987, 259.

8 St. John Damascene. On Holy Images. Translated by Mary H. Allies. (London: Thomas Baker, 1898), 1:15-16.

9 Wriedt, Markus. “Luther’s Theology,” in The Cambridge Companion to Luther. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 88–94.

10 Philip Melanthen , “The Defense of the Augsburg Confession — The Mass.” The Book of Concord. http://old.bookofconcord.org/augsburgdefense/23_mass.html (accessed April 15, 2010).

11 Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. New Ed ed. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1997.

12 John Calvin, “Book 1 Chapter 11.” Institutes of the Christian Religion Translated by Henry Beveridge. N.p., n.d. Web. 1 May 2010. .

14 John Calvin, “Book 1 Chapter 11.” Institutes of the Christian Religion Translated by Henry Beveridge. N.p., n.d. Web. 1 May 2010. .

15 Friedrich Bente, “Historical Introductions to the Lutheran Confessions.” Book of Concord. http://www.bookofconcord.org/historical-18.php (accessed April 18, 2010).

16 Murray, David P . “Lessons From John Knox .” Reformation Scotland. N.p., n.d. Web. 1 May 2010. http://www.reformation-scotland.org.uk/articles/lessons-from-john-knox.php.

17 Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580, Second Edition. 2 ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 215.

18 Thomas Fuller. The Church History of Britain, From the Birth of Jesus Christ Until the Year MDCXLVIII Vol. III. (Albany New York: Bibliolife, 2009, Print), 243.

20 Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580, Second Edition. 2 ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 385.

21 Stephen W. Sykes, The Integrity of Anglicanism. (London: Mowbrays, 1978), 44-50.

23 The word “sacrament” comes from the Latin “sacramentum,” which meant “an oath, a sacred thing, a mystery.” It was tied to being part of a community. I think this understanding is very fitting to the heart of the Anglican Communion.

24 Johann Eck, “Johann Eck’s 404 Theses.” the Book of Concord. http://www.bookofconcord.org/eck404-theses.php (accessed April 30, 2010).

25 “Chapter 25.” Council of Trent. http://www.americancatholictruthsociety.com/docs/TRENT/trent25.htm#2 (accessed May 1, 2010).

26 Quakers emerged out of the Radical branch of the reformation

27 James H. Forest. Praying with Icons. (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2008), 36.

28 Sergei I. Zhuk, Russia’s lost reformation :peasants, millennialism, and radical sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830-1917 (Washington, D.C. : Woodrow Wilson Center Press), 2004, 212.