When I was first beginning to seriously explore my faith in my teens I remember talking to a good friend of mine about the after-life. We were talking about how there were to be no more tears in heaven, because all pain would be taken away (Revelation 21:4). This idea concerned me. I had trouble understanding how someone could live with no pain in heaven if they lived through a life filled with pain. My friend said, “well that’s easy, look at Isaiah 65:17 ‘For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind.’ In heaven”, my friend said, “we won’t even remember this life.”

This bothered me a bit. I liked my life. I loved my family, my experiences, all the good things I had to had happen to me. I felt as if most of what made me who I was was tied up in the memories I had accumulated over the years of life. Without memory, I felt I would cease to be myself. I wanted to make a deal with God, “You let me remember my life, and I will try to too complain about the bad stuff, in fact I’ll try not to even think about it.”

Memory is a difficult theological issue for those of us who believe in eternal life. St. Augustine likens memory to a cave into which each experience of our lives enters and finds a recess into which it dwells. (Confessions Book 10.8) It is a path that allows us to move forward. We learn from our experiences and move ahead with greater creativity and illumination. However some memories can keep us trapped. Hurts we have suffered, or pain we have endured can keep us from moving forward and can control our lives. Memory can be both ally and captor.

To resolve this tension around memory, theologians have offered basically two options for Christians:

You won’t remember a thing OR

The bad memories won’t make you sad anymore

The first option we have already mentioned as the option my friend promoted to me years ago. In this view you will not remember ANYTHING about your life here, but will rather life in a reality free from the captive power and pain of memory. The potential difficulties with this position we have already talked about a bit (loss of identity, loss of good memories, etc). There are additional theological difficulties with this position when we think about the person of Christ. If we affirm Christ, as truly human, is able to empathize in every way with our temptation, being tempted himself (Hebrews 4:15), we cannot believe that we are to loose our memories. Christ’s empathy from solidarity is rooted in his human memory of his human temptation. To deny the eschatological perpetuation of memory is to deny Christ of some of the power of his incarnation.

The first option we have already mentioned as the option my friend promoted to me years ago. In this view you will not remember ANYTHING about your life here, but will rather life in a reality free from the captive power and pain of memory. The potential difficulties with this position we have already talked about a bit (loss of identity, loss of good memories, etc). There are additional theological difficulties with this position when we think about the person of Christ. If we affirm Christ, as truly human, is able to empathize in every way with our temptation, being tempted himself (Hebrews 4:15), we cannot believe that we are to loose our memories. Christ’s empathy from solidarity is rooted in his human memory of his human temptation. To deny the eschatological perpetuation of memory is to deny Christ of some of the power of his incarnation.

The second option is that which was taken up by Saint Augustine, and with him a great deal of Western theological thought. Augustine asks the question, “how does it happen that when I am joyful I can still remember past sorrow?” (Confessions Book 10.14) In this view our bad memories are overpowered by the goodness of God and can even be used for good. For example, memories of loss can draw us towards restoration. In his Confessions

(Book 10.18), Augustine talks about Jesus’ parable of the woman who lost her small coin, if she had not known she had lost something she would never have known to seek it, or how to recognize it when she did happen upon it?

Although I tend to agree more with the second option I still find it to be somewhat problematic. Even though there are many times that memory can be transformed for good there is still an existing element of evil at work in the memory of evil. I recently read a story in the news about a girl who testified at the trial of the man who killed her grandfather. She was unable to even finish what she had to say because she was overcome with grief. It was as if by being required to remember she had to relive the pain that she experienced when she lost him the first time. There are some times when the evil that we experience in our broken world can’t just be ignored or transformed. There are some memories that affect us so deeply that the wounds they inflict can never be reincorporated into our lives in a meaningful way. There are some things that we can’t make sense of, and shouldn’t try to. Evil is not always something we can make sense of. Some things are just senseless tragedies that can’t be rewoven into our lives in any meaningful way. This is why there is a part of me that still wants to believe in Isaiah 65:17.

Although I tend to agree more with the second option I still find it to be somewhat problematic. Even though there are many times that memory can be transformed for good there is still an existing element of evil at work in the memory of evil. I recently read a story in the news about a girl who testified at the trial of the man who killed her grandfather. She was unable to even finish what she had to say because she was overcome with grief. It was as if by being required to remember she had to relive the pain that she experienced when she lost him the first time. There are some times when the evil that we experience in our broken world can’t just be ignored or transformed. There are some memories that affect us so deeply that the wounds they inflict can never be reincorporated into our lives in a meaningful way. There are some things that we can’t make sense of, and shouldn’t try to. Evil is not always something we can make sense of. Some things are just senseless tragedies that can’t be rewoven into our lives in any meaningful way. This is why there is a part of me that still wants to believe in Isaiah 65:17.

There is another way that people talk about memory, a third way. This way affirms that memories have eschatological significance, but also acknowledges there are times in which we don’t want to have to be reminded of all the evil we have experienced. This view is the one that is proposed by Mirslof Volf in his book The End of Memory

. In in Volf states, “Memories of suffered wrongs will not come to the minds of the citizens of the world to come, for in it they will perfectly enjoy God and one another in God (pg 177).” Volf believes that God will bless us bless us with such an immersion in God’s love that we will simply not bring our sufferings to mind. It’s not that our memories have been expunged from our minds, or that our identities have been altered to the point at which we no longer have continuity with who we are today. However the reality of God will be so powerful we will simply stop noticing the hurts because they will stop defining us in the face of the new reality.

I like this idea.

So far we have talked mostly about how memory will function in the final act of our existence. However today we are not living in the eschatology age. We are not living in perfect enjoyment of the love of God. How then are we to live in this day and age? In other words, how does this affect our christian life? As Christians we are called to be instruments of redemption. We are sent as little christs into the world to bring the healing power of the cross to every place. This means that we are called to bring reconciliation and love. We are to work towards loving our enemies and strive towards mending the broken relationships that come into our lives. Although we may not be able to ever completely heal some wounds. I are called to testify to the hope that it is possible in Christ.

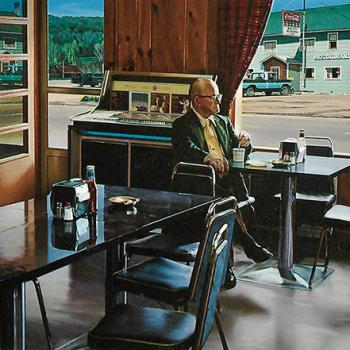

Photo Credit: Fred Burkhart

http://www.burkhartstudios.com/

Please support Fred and his art. He is a friend.