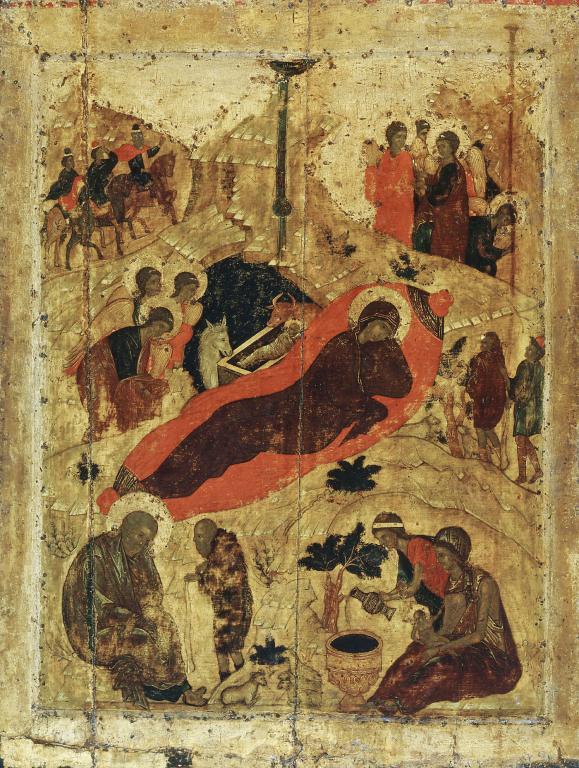

Last week in my “Modern Magi on the Meaning of Christmas” conversation featuring with Scot McKnight, Nadia Bolz-Weber, and Kyle Roberts my conversation partners repeatedly brought up the importance of seeing Christmas as a lens through which we can see God’s action in a world of fear, murder, tragedy. The world is broken, and that’s an important part of the story. One of the things Nadia mentioned that really stuck with me was the idea that we have to keep “Herod in Christmas” We have to be reminded of the dark reality that God’s light is in-breaking into though Jesus. One of the ways that I have found I am reminded is through art. In our home my wife and I hang a print of one of Andre Rublov’s masterpieces, the nativity. This image has become a daily reminder to me of the dirty beauty of the incarnation. I thought I’d share a bit of my thoughts on it with you.

Last week in my “Modern Magi on the Meaning of Christmas” conversation featuring with Scot McKnight, Nadia Bolz-Weber, and Kyle Roberts my conversation partners repeatedly brought up the importance of seeing Christmas as a lens through which we can see God’s action in a world of fear, murder, tragedy. The world is broken, and that’s an important part of the story. One of the things Nadia mentioned that really stuck with me was the idea that we have to keep “Herod in Christmas” We have to be reminded of the dark reality that God’s light is in-breaking into though Jesus. One of the ways that I have found I am reminded is through art. In our home my wife and I hang a print of one of Andre Rublov’s masterpieces, the nativity. This image has become a daily reminder to me of the dirty beauty of the incarnation. I thought I’d share a bit of my thoughts on it with you.

Rublev’s image of the nativity is a compilation of a number of the scenes of the gospel all in one panel. Unlike many paintings that synthesize the Gospel accounts into a single scene, Rublev spits the image into multiple scenes. This move underscores the eschatological understanding that was in the background of the observers. These events were not simply historical events, but live events that were participated in as the community celebrated the liturgy. The unifying theme was the liturgical event of the feast of the nativity which the community celebrated. Each of these scenes belonged in the image, because each of them contributed to the liturgical genius of their rites. We will evaluate each scene in turn.

The Center Cave

In the center of the image is a cave. At the opening of the cave Mary is pictured lying down. She has just given birth, but instead of facing her child, she turns away. This seems strange. There seems to already be a pain between mother and child. The key to understanding this placement of Mary can be found in the image of the child himself. He is wrapped in a cloth that resembles the burial clothes seen around Lazarus, just a few icons to the right.[1] He is also placed in a manger that looks much more like a burial box than a crib. Jesus’ death can already be felt. The incarnation was an acceptance of human mortality and frailness. Mary turns in sorrow from the death of her son. She faces here her own death as well. This is seen in how she is situated; she lies on a red bier, just as she does in the icon of her dormition seen on the other side of the iconostasis.

Around the manger are an ox and a donkey. Rublev has taken the theme of the manger in Luke’s gospel and connected it to the theme of the manger in Isaiah 1:3. The beasts remind us to recognize Jesus as our master. They also indicate the cosmic dimension of salvation. The whole world finds its hope in Christ, and all of Creation is groaning for His revelation.

The cave is black and shaped like a womb. Jesus is clothed in white. This stark contrast of color draws the observer to see Christ as the light of the world, incarnated into a cosmos in desperate need of illumination. This theme is deepened by the decent of divine life in a ray that moves through the center of the canvas. The ray of light splits midway to Christ, into three rays. This reminds the viewer that the incarnation was a Trinitarian action. They are reminded of the description of the angel in the annunciation of Jesus’ birth in Luke 1:35.

The Magi

After observing Mary and the child, the eye is free to begin to rove the rest of the image. At the top left corner we see the magi. Their gestures up into the sky tell us that they have not yet discovered the Christ child. The focus on the Magi in the Orthodox liturgy is not on their gift giving but in their discovery of the light of Christ through the light of the star. Their attention in this icon emphasizes this focus. These Magi are depicted as an old man, a young man, and a middle aged man. This emphasizes that they are symbols of all humanity being drawn into the dawning light of Christ. This hope must have been particularly strongly understood in Moscow, where the feast of the Nativity was being celebrated in the deep darkness of a northern winter.

The Shepherds

On the far right side we see shepherds. There is nothing remarkable about the shepherds in this image. This is perhaps the point. Rublev does not present the angelic declaration in this scene with the same flourish which Luke employees. Gone is the host, gone is the song, gone is the grand pronouncements of counter-propaganda seen in the evangelist’s account. This perhaps is because the empire against which these images were once so powerful is now gone. Moscow has begun to fashion itself as a kind of new Rome in the east. There is no room for anti-imperial sentiment in this icon located at the new center of Russian power.

The Washing of Jesus

In the bottom corner midwives wash the Christ child. This is done in a basin that looks very much like a baptismal font. This account does not appear in the scriptures but instead is inspired by the Protoevangelium of James. In this book a midwife is present at the birth and echoes her own version of the Magnificat at Christ’s birth, as a Sinai-like cloud descends upon the cave (19). The midwife then calls in another midwife by the name of Salome, who verifies that Mary was still a virgin even after the birth of Christ (19-20). These two women function as proto-John the Baptist figures in the icon, washing Christ. This image of the infant being washed would strike a note with the Orthodox community which has, at this point, moved toward nearly all baptisms being done with infants.[2]

The Distress of Joseph

Next to the midwives, in the bottom left corner, is Joseph. This depiction is inspired by the account in Matthew of Joseph’s struggle to remain committed to Mary in spite of his own fears and concerns. This image shows Joseph struggling with his doubts, which are personified by an old man. This man seems to be accusing Mary of infidelity. Joseph presents us with a unique image of faith. His rational mind still can’t understand the incarnation, but he move forward in faith and love. Baggley highlights that the liturgical forefeast of the nativity focuses on Joseph’s doubts and present a narritive of Joseph as a distressed husband over this difficulty and shame of the situation all the way until the Birth.[3]

The Angels

Rublev includes two sets of angels, the set on the left contains three angels, while the one on the right appears to have three but a fourth emerges between the halos of the two standing upright. This right set seems to have three standing upright and one bending down to speak to shepherds. This composition indicates two separate actions, one is the pronouncement to the shepherds the other three seem to be in conversation with one another. The three standing the angels on the left set seem to anticipate the angels that are seen in Rublev’s famous icon of the Old Testament Trinity. In this example there is one clothed red robe and blue robes of Christ, another clothed in a bright red, the same color as Mary’s couch, and which seem to follow through the fabrics seen throughout the festal icons in the iconostasis.[4] This red color represents the fire and energy of the Holy Spirit which is seen at work though God’s intervention throughout the festal cycle.[5] A final angel is hidden, indicating in incomprehensibility of God.[6] This is the same pattern used to present the three upright angels on the right side. In an image where the scale of the figures is clearly not a primary concern, Rublev takes special care to make sure all three figures in his sets are drawn with the same dimensions, showing the coequal dignity of the three persons. They underscore the Trinitarian orchestration of these events and offer a reminder of the divinity of Christ which is still maintained in spite of the lowliness of the incarnation. Their presence also reminds the viewer of the appearance of angels in the annunciations of both Jesus’ and John the Baptist’s birth, as well as their role in the prophetic promises of the Old Testament, from the promise made to Moses to their role in the visions of the prophets.

The Plants

Around the cave there is growth sprouting from the rocks. This is not coincidental. The liturgical apolytikion for the forefeast of the nativity states that the tree of life “has blossomed from the virgin in the cave” and those that eat of it “shall live.”[7] Sheep are pictured eating of the plant at the bottom of the icon. They don’t appear to be the sheep of the shepherds on the right. Instead these sheep seem to be the flock of the good shepherd, Christ. Another tree grows, seemingly, from the waters of the font. This is simultaneously the tree of life and the cross. The viewer is reminded of both the drowning and resurrection found in baptism.

Concluding Remarks

This icon of the Nativity is a remarkable work of exegesis. It closely reads the gospel accounts, and brings relevant themes and images to life. It is deeply rooted in the traditions of the Church, incorporating Old Testament imagery, liturgical hymns and prayers, and images from the broader interpretive tradition. It is also a composition rooted in the place and time of the author. Rublev lived in a time of Great trial.

He was born during a time of both religious persecution and revival. Russian territories had succumbed to the Mongols in the thirteenth century. Although the Mongol invaders were generally tolerant of the religions in the areas they conquered, the initial conquest had resulted in iconoclasm and persecution of Orthodox Christians throughout the regions that fell under the Mongol rule. The death and destruction that came with this conquest left an impression upon the Russian orthodox people of their great need to pray for the dead, and a constant fear of conquest by the foreign power. This image is came out of the ashes of persecution and helped ignite a new faith and hope. I pray we can find similar lamp-posts in our own lives this Christmas.

Notes:

[1] Rublev’s Nativity emerges out of a collaborative effort to paint the icons for the Annunciation Cathedral. Rublev appears to have been tasked with painting the left side of the Festival row of the iconostasis. It is believed he painted the Entry into Jerusalem, the Nativity of Christ, the Raising of Lazarus and the Transfiguration. See a reconstruction here.

[2] Baggley, Festival Icons for the Christian Year, 68.

[3] Ibid., 37.

[4] See Figure 1

[5] Solrunn Nes, The Mystical Language of Icons (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005), 38–39. and Gregory Collins, The Glenstal Book of Icons: Praying with the Glenstal Icons (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002), 89.

[6] For more on the importance of these color’s in Rublev’s work see: Elizabeth Zelensky and Lela Gilbert, Windows to Heaven: Introducing Icons to Protestants and Catholics (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2005), 47–48.

[7] Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology (Downers Grove IL: InterVarsity Press, 2013), 119.