I speak endlessly on identity. The audience and the details vary but at the heart of everything I do, personally and professionally, there is most often some study of identity.

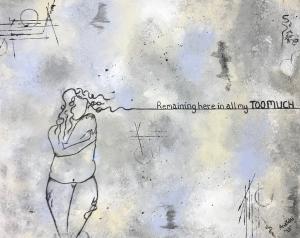

The spirituality I practice, the posture I take when pursuing justice, the art I create, and the very name I call myself are all connected to identity. I am constantly finding myself on this seesaw of fully and beautifully knowing who I am or being terrified that I have no idea and never will. Like most westernized people, a disproportionate amount of that knowing is wrapped up in my profession and what I produce for others. Unexpectedly losing a job, particularly one that has so thoroughly shaped your world for years, is a devastating blow to one’s sense of self. I should know. It sent me right back to therapy; reminding me that therapy is wonderful and the whole world should get some.

In the eight weeks since leaving my job and navigating the new intimidating possibilities of pursuing justice ministry independent from an institution, my seesaw has thrashed me about quite a bit. Last night I was provided a timely reminder of who I am and where I come from.

Immigrating to the U.S. as a toddler, most of my life has been spent living in the Latin diaspora.

Yo soy Venezolana.

I was born in Caracas, Venezuela and, to this day, I remain a Venezuelan citizen. I haven’t been home since I was three, I no longer speak fluent Spanish, and I know few other Venezolanxs (ours is one of the smaller Latinx populations in the U.S.). I am so proud to be Venezuelan, to be Latina, and to be a brown-skinned woman but I struggle with the loss and detachment that so many living in the diaspora have experienced. This common struggle is a challenge to one’s identity.

Opportunities to overcome that struggle are exhilarating and terrifying. What if you’re exposed to be less than enough?

For me, such an opportunity took the form of being invited to participate, as an artist and storyteller, in an event called “My Turn: Airing Art and Stories of Venezuela.” This showcase of Venezuelan experience and talent was held last night, April 11th. This date was chosen as an intentional reminder that “prohibido olvidar Venezuela” (“Forgetting Venezuela is forbidden”)- it is the anniversary of the 2002 protest where Venezuelan marchers lost their lives at the hands of the state.

The intent of the evening was to say, “My Turn”. It was our turn to address the erasure of Venezolanxs from the immigrant and refugee narrative, to shed light on Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis and all that our people have and continue to endure, and to showcase the beauty and art of Venezuela.

I am deeply passionate about the practice of name reclamation and speak often of how my name is one of the things that tether me to my people so it made sense that this would be the story I found myself telling last night. I spoke of how, having spent the majority of the first 3 years of my life in an orphanage run by the Catholic Church, I don’t carry memories or tokens of my brief time with my birth mother.

There is exactly one thing my mother ever gave and it was the first thing I ever owned. The name AnaYelsi Velasco-Sanchez. It belonged to me for 3 years before it was stripped away. When I was 3 I joined the countless Brown and Black babies that were displaced as a result of 1980’s wave of international adoptions. Coming to the U.S. as a child meant forced assimilation and AnaYelsi was erased to make room for Ashley.

I spent ‘my turn’ telling people about my journey to reclaiming my name and how that one powerful act at 15 years old was the beginning of a lifetime of shaping my own identity. The act of sharing my name reclamation story is not new but doing so in a room full of Venezuelans, more than I had ever seen gathered together before, had me speaking with shaky breathes. Having Venezuelans come up to me at the end of the evening to share their name stories and to affirm me as one of their own was healing. There is something precious about having a young Venezolana hug me and matter-of-factly say, “You are a true Venezuelan.”

That was a gift.

The evening ended as all should – retreating to someone’s apartment to eat late-night homemade Venezuelan cachapas and discussing religion and race between each cheese-filled bite. I was asked to share my thoughts on iconoclasm (the rejection or destruction of icons). The usual casual conversation, yes?

I named how the prevalence of inaccurate imagery such as “White Jesus” is a dangerous byproduct of religion as a tool of colonization but also noted that there is a place for icons in spiritual practice- they can be uniquely precious for Christians of Color. Christianity has been so thoroughly appropriated that we often forget that, not only is it for us, it was born from us.

On my small altar in my bedroom, there are several beautiful icons created by the artist Jen Casselberry. They bear the images of Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz, Moses the Black, Dolores Huerta, and Sylvia Rivera – leaders of Color that have and are giving their lives in pursuit of what is just. Looking at these images, hearing the stories and music of other Venezuelans, giving voice to my own experience… it is all connected. These things give me roots. They fortify me in a world that tells me I am simultaneously not enough and far too much. They remind me of the legacy of People of Color (Christian and otherwise) and my own capacity to not just survive but to flourish. When the circumstances around me are challenging my sense of self these things become a sustaining force. I cannot separate my identity from the identities of others. We are interlocked and when I lose sight of myself they are there to remind me of who I am.

Forgetting is forbidden.