There are twelve months in all the year,

As I hear many men say,

But the merriest month in all the year,

Is the merry, merry month of May.

(Child Ballad 140B.1 – Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires)

The vibrant verdant land, having woken from its winter slumber in bursts of leaf and bud, with long days and the promise of warm golden sunshine, brings with it the assurance of fertility. The covenant of life and peace is displayed upon the earth and it is a time of rejoicing the fulfilment of the promise of the gods to bring forth the fruits that nourish and sustain our divine gift. The world is alive and blossoms into fulness, the carnal activity of all life seemingly driven by unseen forces toward consummation of that contract between life and death, the union of male and female which secures through the flame of Hope.

The flowery garland for the May Lady was an essential element in the rites of May Day, for the Lady represented the return of spring and was crowned as herself embodying the occasion that was being celebrated. This occasion was both more solemn and more complex than we now realise. (Wilkins, 1969)

May Eve, Roodmas, has a tradition of association with witches in the myths of historic Europe. Assuming a distinctly Marian character in the Middle Ages, witnessed by a wealth of literature that attests to this, it is apt that the myth of Robin Hood is incorporated into this theme as the paragon of verdant worship of the divine feminine, fecundity, courtly love and merriment. Throughout the traditions and customs of merry old England, one which persists is that of the mummers’ play, folk plays using mask and disguises (origin of the ‘guisers’) performed during and marking key turnings of the wheel of the year. This is the time when St George duels his dark twin and is slain, only to be resurrected by the good Doctor in order that he may triumph in his turn when the nights are long.

In a letter to Ronald Chalky White, then Summoner of the Clan of Tubal Cain, and future founder of The Regency, Robert Cochrane made a handwritten note indicating that Chalky was wrong about May and that it was a ‘Wedding Breakfast’. From this titbit, we can conclude that the author regarded May as a feast to follow a wedding, which properly took place in the conjunction of masculine and feminine in equality at the Vernal Equinox, seen in the tradition of Lady Day. As we have discussed previously, the themes of sex, life and death traditionally predominated Lady Day, seen in the West through the combined Christian mysteries of Jesus divine conception and crucifixion occurring upon the same day at Easter. In addition, the old calendar marked the same time period as the commencement of the new year. This alignment, when night and day are equal, is celebrated as the marriage of twin forces, the two sides of the coin which must be paid. In this, tradition spanning at least two millennia, suggests that May, one of the first great ‘Fire Festivals’, celebrates this marriage through feasting, dancing and merrymaking.

The Gallican Rite, the prevailing Western Liturgy of the Catholic Church during the first millennium AD, was known to have comingled with Celtic customs in Ireland. Prior to the marrying of the Gallican and Roman Rite, the Feast of the Cross was celebrated on May 3rd, known variously as Roodmas, Crouchmass. While Easter marks the Passion of Christ and Crucifixion, Roodmas celebrates the cross as the instrument of salvation. The connection of this cross (of the elements?) bears considerable investigation in relation to May Eve rituals, least of which includes the image of the World Tree, the Maypole, Irminsul, and the Anglo-Saxon poem, Dream of the Rood, in which the tree of crucifixion narrates its tale.

Listen! The choicest of visions I wish to tell,

which came as a dream in middle-night,

after voice-bearers lay at rest.

It seemed that I saw a most wondrous tree

born aloft, wound round by light,

brightest of beams. All was that beacon

sprinkled with gold. Gems stood

fair at earth’s corners; there likewise five

shone on the shoulder-span. All there beheld the Angel of God

(The Dream of the Rood)

The Maypole, much recalled in neopagan communities, is a reflection of the world centre, axis mundi, about which grinds the mill of fate, with joyful, childlike dances. Little remembered today is that the Maypole is a representation of the axis mundi as the anima mundi. The pole is the embodiment here of the Rose Lady, the May Queen, and is adorned with a garlend of roses, a Rosary, or rose garden, which is also worn by the bride who becomes the living May Queen, embodying the spirit of the festivities. While the twin aspects of the Horn Child, Robin and his ‘other’ contest for the right to attend the bridal chamber, the May Queen presides in Her resplendant fulness.

There is another Bride who wears a garland and who enters into the history of the rosary. Why did the Flamen of Vulcan (to use Plutarch’s formula) sacrifice to Maia on May Day? The answer is that Maia, the May Lady, is the wife of Vulcan (Hephaistos). (Wilkins, 1969)

Here we come to the essence of the May Day celebrations from the perspective of the witches festival. The Bride here is, as we see, Maia, and her spouse is the blacksmith god himself, Vulcan, Tubal-Cain. Identified at the time of the May celebrations as Robin, here we see the Horn Child as “the Wild Hunstmsan, Robin surnamed Hood or Wood, who is sometimes identified with Woden”, as in Robin Wod (Wilkins, 1969). Interestingly enough, Woden was reckoned through Roman syncretism to be identified as the god Hermes or Mercury, whose mother is accordingly Maia. Therefore, the May Bride, the Rose Queen, is the mother AND bride of the Horn Child in her own turn, this time taking the hand of the Lord of the Dead as the approach to the Midsummer heralds the shift in sovereignty and passing of the crown between the tanists.

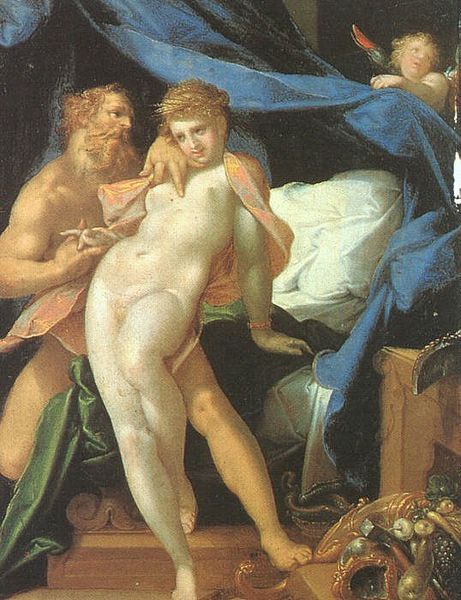

While these two battling brothers contend for the favour of the Rose Queen, it is to Her that we now turn our attention. We have discussed the Tree as the divine feminine, but it is something that is often overlooked during May rituals marked in the pagan and witch calendars. In ancient customs, the Venusian Queen of Heaven, whether in Her guise as Aphrodite, Ishtar, Ashtaroth, Isis, Mary, was at various times adorned with a crown of roses. Eithne Wilkins in her seminal book, The Rose-Garden Game, describes in detail the three crowns, or garlands, which adorn the Maypole, representing the Three Mothers as celestial progenitors of the three worlds.

At the top of the May-pole, which stands on a grassy pedestal like a three-tiered wedding cake, are three hoop-garlands with small gilded pendants dangling from them, the hoopes decreasing in diameter as they descend. (Wilkins, 1969)

The significance of this triple crown, which has been physically represented in historical offices including the Hemhem crown of Egypt, worn by the god ofmagic, Heka, as well as Akhenaten and Tutankhamen. Most obvious today is the Papal triple tiara crown, supposedly bestowing the triple authority to the supreme Vicar of Christ upon Earth.

Finally, Wilkins identifies that the Lady of the May in traditional May Day custom is “decorated in the same way as the May-tree because each is equivelant to the other; in rosary-symbolism the God-Bearer [Mother of God] also appears as the rose-tree, and in general a tree is a symbol of the Great Mother”(Wilkins, 1969).

The Tanist Duel

The triple motif is seen again in the Child Ballad, number 140B, which sings of Robin Hood rescuing three of his men form the Sheriff of Nottingham. Significantly, this Ballad is set during the ‘merry, merry month of may,’ and sees brace Robin adorn the guise of an old man in order to save the three from hanging. Here we have some traditional English themes which might go unnoticed today, but would be recognisable in the 15th Century when this lyric was supposedly first sung. As the mythic figure who presided over crossroads and hanging, the folk spirit of Woden looms once again and, as Robin dons the old man’s garb, in affect transforming into his dark aspect, we see yet again the traditional description of Odhinn/Woden:

Then he put on the old man’s hat,

It stood full high on the crown:

‘The first bold bargain that I come at,

It shall make thee come down.’

Ten he put on the old man’s cloak,

Was patched in black, blew and red;

He thought no shame all the day long

To wear the bags of bread.

(Child Ballad 140B. 13-14)

The reference to the oath that Robin makes as he dons each item of the old man comes to pass as he, in his meeting with the Sheriff, summons his men from where they hide. In the first instance, the high crown signifies a hill, and the next a plain. Again, the mythic imagery of the hill and plain harkens back to the Arthurian and Grail cycles popular during the same time, as well as the mound which the old man rules as Gwyn ap Nudd. Lastly, we must note that Robin’s knowledge of the three men held captive is arrived through the wise old woman he meets first upon his travels, being Dame Fate steering the transformation before the gallows form green Robin, to Old Man – “But the merriest month in all the year is the merry, merry month of May.”

As the dynamic between the twin masculine forces plays out, the seasonal passage through the May dawn has been ritually celebrated both in pastoral and folk customs throughout history. From Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus, Castor and Pollux, Hengist and Horsa, Enkidu and Gilgamesh, we see these twins, or one and the same, pass through trials whereby one becomes discarnate, immortal, takes up office in the eternal, whilst the other remains associated with the office of the earthly, draconian and fertile realm; light and dark, night and day. Of these mythic heroes, who are commonly depicted as and associated with horses, one pair is especially worth a little investigation here.

Enkimdu and Dumuzi

In the Sumerian myth, identified by Kramer as ‘Inanna Prefers the Farmer’,(Kramer, 1961) we begin to see quite how ancient the May Day celebrations are, encapsulated within the very heart of our festivities that have survived for millennia. Within this myth, the figures Enkimdu, the god of farming, competes with Dumuzi the Shepherd for the affection and marriage of Inanna, the prototype of the Marian divinity which presides over the May. In the same pattern as the myth of Cain and Abel, and perhaps informing it, in this rendition it is the Shepherd who triumphs, although we learn a great deal more about the fate of Abel through this myth. As the husband of Inanna, Dumuzi is destined, following Her descent to the Underworld, by Her decree to spend half the year in the Underworld, emerging as a prototype of the dying-resurrecting god.

Inanna took Dumuzi by the hand and said:

“You will go to the Underworld

Half of the year. (Kramer and Wolkstein, 1983)

We can only guess that the competing between the Shepherd and Farmer takes place around May Day but, within our modern rendition of this hoary myth making, it is most appropriate that we recall the significance of these. As the Marian world tree, cognate with Inanna, and the competing gods of the flock and the grain, they must enjoin the contest for the right to the hand of the Rose Queen and determine the succession of the year under the aegis of Fate.

And so, in Traditional Witchcraft, the Blood Acre is fastened upon certain knots of the year and the prescience that the verdant angel must take his leave of the world, and the Rose Queen be escorted to the realm of the Lord of the Dead, is witnessed during this high time. The path which connects May with Hallows finds its hidden mystery here through the path of the dragon, in a moment of ingress. In the midst of the sacred union, the consummation of the divine marriage as a hieros gamos reflects the depth of wisdom that life seeded at this time is destined to return to the underworld from whence it comes. But, for now, we dance the Mill of Fate beneath the great May-tree, select our embodied Rose Queen and glimpse in the leaf the mask of the Green God of the spring.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Kramer, S. N. (1961) Sumerian Mythology. Revised. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kramer, S. N. and Wolkstein, D. (1983) Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth. 1st edn. Harper & Row Publishers.

Wilkins, E. (1969) The Rose-Garden Game: The Symbolic Background to the European Prayer-Beads. London, Southampton: The Camelot Press Ltd.,.