On this weekend after Thanksgiving, one of the many things I am grateful for is the opportunity to be a Unitarian Universalist.  I am grateful to be part of a tradition that counts among its ranks such luminaries as John Adams, Ben Franklin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Susan B. Anthony, Clara Barton, and Louisa May Alcott — as well as Ray Bradbury, Sylvia Plath, Frank Lloyd Wright, and so many others. But, even as I list, with gratitude, the names of these famous UUs, who helped blaze the trail that we now walk, I’m reminded that, upon closer inspection, each these figures has a unique and often complex relationship with Unitarian Universalism that varied at during different parts of their life. So it can often become difficult to say on a simple list who was and wasn’t part of one of the traditions that merged together in 1961 to form the Unitarian Universalist Association.

I am grateful to be part of a tradition that counts among its ranks such luminaries as John Adams, Ben Franklin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Susan B. Anthony, Clara Barton, and Louisa May Alcott — as well as Ray Bradbury, Sylvia Plath, Frank Lloyd Wright, and so many others. But, even as I list, with gratitude, the names of these famous UUs, who helped blaze the trail that we now walk, I’m reminded that, upon closer inspection, each these figures has a unique and often complex relationship with Unitarian Universalism that varied at during different parts of their life. So it can often become difficult to say on a simple list who was and wasn’t part of one of the traditions that merged together in 1961 to form the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Among those ambiguous, borderline figures is our controversial third U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. As a UU World article a few years ago said,

The consensus seems to be that he had strong Unitarian sympathies but did not formally belong to any Unitarian church…. Those who prefer to regard Jefferson as an independent deist tend to highlight the letter where he says, “I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know.” Those who want to hold him up as a UU role model point to another letter where he says, “The population of my neighborhood is too slender, and is too much divided into other sects to maintain any one preacher well. I must therefore be contented with being a Unitarian by myself.” Jefferson was a regular donor to St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Charlottesville, Virginia, and served on its vestry, but he was also known to worship at Joseph Priestley’s Unitarian church in Philadelphia.

I am personally grateful to count Thomas Jefferson as among history’s famous UU forebears, but whether the historical Thomas Jefferson would approve of being on a twenty-first century list of famous Unitarian Universalists is one side of the equation. Another side is whether all contemporary UUs want to claim Jefferson.

On one hand, the short-list of his accomplishments is stunning: chief author of the Declaration of Independence, the first U.S. Secretary of State (under George Washington), the second Vice-president of the United States (under John Adams), the third President of the United States (elected for two terms), coiner of the phrase “wall of separation between church and state,” author of the landmark Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase, and founder of the University of Virginia. From this perspective, the reasons to claim Jefferson as a famous UU seem obvious. On the other hand, Jefferson infamously participated in the moral evil of slavery. In many ways, Jefferson was far ahead of his time, but in his role as a slave master, he was a product of his time.

Some of you may recall that last year, the Thomas Jefferson District of the Unitarian Universalist Association (which includes Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) voted overwhelmingly at the district’s annual meeting to change its name to the Southeast District. This name change proposal had come to a vote at two previous annual meetings (in 1997 and 2010), but had failed to reach the needed two-thirds majority. That second vote fell only three votes short.

As I have reflected on this debate, I am of two minds. Thomas Jefferson is one of the many reasons that I was drawn to Unitarian Universalism: his lifelong love of learning, his use of reason to separate antiquated superstition from the authentic core of religious experience, and his emphasis on the need for each individual to discern religious truth for him or herself. For many reasons, I continue to find Jefferson to be a fascinating human being. As President John F. Kennedy said in 1962 at a dinner in honor all living recipients of the Nobel Prize, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” From this positive angle, I had mixed emotions when I learned of the recent name change of the former Thomas Jefferson District of the UUA.

From another angle, the history of how the name change vote gained momentum is worth noting. As Unitarian Universalists have increasingly embraced the difficult, but vital, goal of becoming more multicultural, anti-racist and anti-oppressive, the wisdom of predominantly holding up privileged white men from our past has been called into question. Yes, Thomas Jefferson’s many courageous stands for reason and religious liberty deserve to be celebrated. At the same time, Jefferson had some deeply troubling views about American Indians and African Americans.

Although there had been dissatisfaction for many years with the name “Thomas Jefferson District,” the catalyst for change came in 1993 when the Unitarian Universalist Association’s General Assembly was held in Charlotte, North Carolina. During this event, it became obvious how naive many white UUs had been to how painful it was for many people of color for Thomas Jefferson’s name to be constantly lifted up without an accompanying caveat about his faults. The flash point was a “Thomas Jefferson Ball” in which attendees were “invited to attend in period costume.” Hope Johnson, an African-American UU minister, expressed the frustration of many UUs when she “asked whether she and other African Americans should wear ‘rags and chains’” for their period costume. This episode helped galvanize a movement to change the name of the Thomas Jefferson District that grew for the next 18 years until it succeeded last year.

These tensions about Jeffersons’ strengths and weaknesses are the turbulent currents underneath my goal this morning of articulating what it might look like to practice a Jeffersonian spirituality for today. To begin with the more positive aspects, I feel fairly safe in speculating that a Jeffersonian spirituality for today would be Unitarian Universalist. In 1822, Jefferson wrote in a letter, “I rejoice that in this blessed country of free enquiry and belief, which has surrendered its creed and conscience to neither kings nor priests, the genuine doctrine of only one God is reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the U.S. who will not die a Unitarian.”

Jefferson’s prediction was incorrect, but perhaps his cutting-edge religious sentiments are only now coming to fruition in our own day with the rise of the so-called “Nones,” many of whom self-identify as “Spiritual, but not religious.” These “nones” are prime candidates for Unitarian Universalism, where you can be both spiritual and religious — or where you can be an atheist, humanist, or agnostic, and still want to be part of a community that will welcome you and encourage you in your free and responsible search for truth and meaning.

A Jeffersonian Spirituality for today would also be open to be the best of modern scholarship and science. Jefferson was a voracious, lifelong reader across all disciplines. And the only sense in which he was a Trinitarian was in his reverence for Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and John Locke. He called them “my trinity of the three greatest men the world has ever produced” (260).

Relatedly, a Jeffersonian Spirituality for today would be unafraid to question sacred cows. As the congregational consultant Bill Easum joked in the title to one of his books, Sacred Cows Make Gourmet Burgers. The consummate example in Jefferson’s life was his audacious project of using a knife to remove the parts of the Christians Gospels that he found contrary to human reason in order to cut and paste his own Jefferson Bible.

A Jeffersonian Spirituality for today would also emphasize firsthand religious experience, similar to the emphasis on “direct experience” as the first source of Unitarian Universalism.Reacting against the Establishment religion of his time in which tax dollars were used to support one state-sanctioned religion over others, Jefferson was against sacerdotalism: he rejected the idea that priests had a special access to reality that was unavailable to everyone else (473). That’s why I’m not your priest, but your minister. I’m not the one exclusively endowed with the ability to intervene with the divine on your behalf, but the one who stands beside you and accompanies you on your journey.

In addition, looking at Jefferson’s lifelong habit of hosting convivial, freewheeling dinners with both his friends and political opponents, a strong argument can be made that a Jeffersonian Spirituality for today would be hospitable (394-395). I would even hazard to say it would be Eucharistic in the broadest and best sense of that word.The authentic core of Jesus’ teachings was strongly influential on Jefferson. And a core of Jesus’ work was transforming society through eating meals with everyone — from friends to enemies to strangers.

There is much more that could be said about a Jeffersonian spirituality today such as how it would also be open to mystery; Jefferson did believe in an afterlife (472). But for now I need to transition to how a Jeffersonian Spirituality for today would need to learn from the errors of the original Jeffersonian Spirituality.

Jefferson was in so many ways ahead of his time. Consider the implications of the words he inscribed into the Preamble of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” These truths, however, were not self-evident to most people in Jefferson’s day, and we are indebted to Jefferson, John Locke, and similar figures for helping make these truths seem more widely self-evident (107). Similarly, the American experiment in self-government was an experiment that had no guarantee of success. And we are likewise indebted to Jefferson and other founders of our country for helping secure the success of our government that is founded not on the hereditary right of a king, but on the “consent of the governed.” In other ways, Jefferson was, like all human beings, a product of his time and place, particularly in his views about American Indians and African Americans. Jefferson did not believe widespread multiculturalism was possible. He could not foresee the path to an America that would elect a biracial President named Barack Hussein Obama to two terms in office.

Regarding American Indians, Jefferson said, “I would never stop pursuing them while one of them remained on this side of the Mississippi” (111). Regarding slavery, Jefferson owned more than 600 slaves over the course of his life: “He inherited 150 (from his father and his father-in-law) and bought roughly 20: most of the others were born into slavery on his lands. From 1774 to 1826, Jefferson tended to have about 200 slaves at any one time (the range ran from 165 to 225)” (48). And Jefferson’s solution for ending slavery was similar to his recommended approach toward American Indians: a removal of the so-called “problem” element to ensure the security of the “white” way of life from which Jefferson benefited immensely.

Early in his career, Jefferson did try to pass a law in Virginia that would emancipate “all [slaves] born after a certain day,” but it was contingent upon “deportation at a proper age” for the freed slaves. But that compromise measure failed. And even at the end of his life, he maintained, “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free; nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government” (124). Further complicating Jefferson’s views, DNA tests in recent years have confirmed that Thomas Jefferson had multiple children with his slave Sally Hemings, who incidentally was the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife. (Jefferson’s father-in-law had six biracial children with Sally Hemings’ mother of whom Sally was the youngest.) Specifically regarding the children of Jefferson and Sally Hemings, “in one case the resemblance was so close, that at some distance or in the dusk the slave, dressed in the same way, might be mistaken for Mr. Jefferson.” But “Mr. Jefferson never betrayed the least consciousness of the resemblance” (454-455).

Thus, a chorus of opinion holds that Thomas Jefferson’s greatest failing was his entitled embrace of white privilege. One response is to take Jefferson down from the pedestal of historical memory, as was done in the removal of his name from the title of the Southeast District of the UUA. A related response is to turn the focus on ourselves. Championing the Jeffersonian attributes that we admire is easy, as is criticizing the Jeffersonian attributes we deplore. So perhaps the more challenging invitation of a Jeffersonian Spirituality for today is asking how our cultural context causes us to tolerate discriminatory practices that future generations will find as repugnant as we find Jefferson’s tolerance of slavery.

I would invite you to reflect on what standard parts of our culture you think future generations may find deplorable. For myself, I will confess that as I wrote this post a few days ago on Black Friday, my search for a contemporary parallel was likely influenced by that timing. As an e-postcard circulating on Facebook says about Black Friday, “Only in America, people trample others for sales exactly one day after being thankful for what they already have.” Or as comedian John Fugelsang tweeted, Black Friday is the shift “from Thanksgiving to Thingsgetting.”

This Black Friday context, reminded me of an essay one of my favorite philosophers, the late Richard Rorty, wrote back in 1996 titled, “Looking Backwards from the Year 2096”:

Just as twentieth-century Americans had trouble imagining how their pre-Civil War ancestors could have stomached slavery, so we at the end of the twenty-first century have trouble imagining how our great-grandparents could have legally permitted a C.E.O. to get 20 times more than her lowest paid employees. We cannot understand how Americans a hundred years ago could have tolerated the horrific contrast between a childhood spent in the suburbs and one spent in the ghettos. Such inequalities seem to us evident moral abominations, but the vast majority of our ancestors took them to be regrettable necessities…. (243)

And a regrettable necessity is precisely how Jefferson viewed the presence of American Indians and African Americans in a land in which he thought it was preferable for rich white men to rule.

As I was reflecting on alleged “regrettable necessities” throughout history, the tragically predictable Black Friday headlines began to roll in: “San Antonio Man Allegedly Pulls Gun On Line-Cutting Black Friday Shopper,” “Man Threatens To Stab Kmart Customers As Black Friday Line Gets Ugly,” and “Walmart Strike Hits 100 Cities, But Fails To Distract Black Friday Shoppers” My thoughts in response were, “How can we shift the focus of our society so that we are less shaped by desperate, frenzied consumerism?” and “From the perspective of Thanksgiving’s embrace of gratitude, at what point have we as individuals and as a society achieved ‘enough?’”

I’m not saying that it is inherently wrong to be rich, nor am I saying that profit motive is bad. Instead, we need an stronger commitment to the common good that puts emphasis not on a bottom line of profit alone, but on a “triple bottom line of people, planet, and profit.” And we need to work to change the parts of our society that cultivate constant dissatisfaction, short-circuit gratitude, and create a false perception of economic status.

For example, perhaps you heard during the election or in the current debate about the impending “fiscal cliff” that the U.S. middle class is anyone whose combined family income is over the poverty line, and less than $250,000 a year. But here’s one columnist’s description of why that framework is problematic:

If the middle class’s ceiling is $250,000 and its floor is the poverty line, then 83% of Americans are middle class. That number defies common sense. More troubling is that so many ostensibly middle-class Americans aspire to be rich. Our expansive use of the term middle class gives 98% of the people permission to feel that they’re missing out on the good life, that they should keep grasping for more. But the aspirations of the relatively well-off should not stand in the way of the basic needs of those the economy is leaving behind. The solution includes a simple rhetorical shift: daring to call those with six-figure salaries what they are—rich.

These statistics aren’t intended to be bad news. This information may be good news: you may be rich, and not know it! Instead, the invitation is both for more people to realize they are rich and to acknowledge that the threshold for being rich is much lower than is often recognized.

Moreover, for many years, studies about the Jeffersonian “pursuit of happiness” have shown that the reciprocal relationship between increased income and increased happiness decreases precipitously once you make $75,000 per year. Science has also demonstrated that generously helping others makes us happier than indulging ourselves.

Naming that the threshold to enter the upper-class in our society is more like $100,000/year, not $250,000/year, could give a larger percentage of our population permission to be satisfied with their current wealth and less resentful of attempts to secure a social safety net for the poorest parts of our society. Likewise, how might our societal mindsets be changed with an emphasis not on “Who Wants to Be A Millionaire?” but on research showing that “beneficial effects of money [on happiness] taper off entirely after the $75,000 mark”?

Jefferson’s white privilege blinded him to the possibility of a multicultural society, which we now know is not only possible, but preferable to the rule of a white male aristocracy. At his best Jefferson knew that “all [people] are created equal,” but like so many of us, he failed to fully live up to his best ideals. This morning, I’ve been inviting you to consider that the easier task is criticizing Jefferson’s faults from our perspective 200 years later on the other side of a bloody Civil War and a hard-won Civil Rights movements that helped us achieve the still-imperfect equality that we do enjoy today. The harder task is confronting the parallel truth that just as Jefferson was unable (or unwilling) to see a path toward less racial inequality, we may be just as unable (or unwilling) to see the path to less class inequality. The invitation is to learn from Jefferson’s negative example, and realize that our culture doesn’t have to be this way. Social reforms throughout history have forged a new status quo that, to many people, were unimaginable until they became the new normal. Jefferson was born a citizen of the British Empire, and died a free citizen of a free nation.

Those of you who have seen the film Lincoln have been reminded of the complicated machinations behind the passage of the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery once and for all in this country. A similar hard fought sea change is washing over our country today concerning same-sex marriage. We can and have changed. We can and must continue to change our society for the better. And as we struggle for social change, it is important to remember that, “The loss of privilege is not the same as reverse discrimination.” The loss of privilege — male privilege, white privilege, heterosexual privilege, or socioeconomic privilege — is a move toward social justice; it is not the same as reverse discrimination.

As this post ends, I invite you to reflect on what it might mean for you to incorporate some aspect of a Jeffersonian Spirituality into your life.

Do you feel led to a courageous embrace of reason to separate superstition from authentic religious experience?

Do you feel led to practice an inclusive hospitality that invites diverse people to break bread together?

Or perhaps you feel led to do your part to help change some systemic part of our society that fails to live up to the best of the Jeffersonian vision — that, “all [people] are created equal, that they are endowed with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

For Further Reading

- Edwin S. Gaustad, Sworn on the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson (Library of Religious Biography).

- The Jefferson Bible, Smithsonian Edition.

- “Henry Wiencek Responds to His Critics: The author of a new book about Thomas Jefferson makes his case and defends his scholarship” (November 14, 2012), available at http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Henry-Wiencek-Responds-to-His-Critics-179166141.html#ixzz2DOCbi5wn.

- Elise Hu, “Publisher Pulls Controversial Thomas Jefferson Book, Citing Loss Of Confidence” (August 09, 2012), available at http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2012/08/09/158510648/publisher-pulls-controversial-thomas-jefferson-book-citing-loss-of-confidence.

- Paul Harvey, “The Quixotic Task of Debunking David Barton,” available at http://www.religiondispatches.org/books/atheologies/6033/the_quixotic_task_of_debunking_david_barton/.

- Barbara Bradley Hagerty, “The Most Influential Evangelist You’ve Never Heard Of,” available at http://www.npr.org/2012/08/08/157754542/the-most-influential-evangelist-youve-never-heard-of.

Notes

1 For more details on who was and wasn’t historically a Unitarian, Universalist, or Unitarian Universalists, see Gwen Foss, A Who’s Who of UUs : A Concise Biographical Compendium of Prominent and Famous Universalists and Unitarians (U.U.s), Fourth Edition. Prior to the 1961 merger that created the “Unitarian Universalist Association,” most people on lists of famous UUs were technically only “Unitarian” or “Universalist” not both.

2 Peg Duthie, “Was Thomas Jefferson really one of us? What do we mean when we claim a historic figure as ‘one of us,’ anyway?” (November/December 2004), UU World, available at http://www.uuworld.org/ideas/articles/2892.shtml. Also, the state of Maryland is part of the “Joseph Priestley District,” which covers Delaware, Maryland, Southern New Jersey, Eastern Pennsylvania, Northern Virginia, and Washington D.C. It’s namesake, Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) was a full-time Unitarian minister, who discovered Oxygen during his free time. Priestley’s 1793 book A History of the Corruptions of Christianity and his 1803 book Socrates and Jesus Compared were influences on Thomas Jefferson and helped inspire the famous Jefferson Bible (see the Smithsonian Edition of The Jefferson Bible, 23-24).

3 “Remarks at a Dinner Honoring Nobel Prize Winners of the Western Hemisphere.” (April 29, 1962), The American Presidency Project, available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8623.

4 Michelle Bates Deakin, “Thomas Jefferson District changes name: Delegates vote overwhelmingly to become Southeast District,” (6 May 2011), available at http://www.uuworld.org/news/articles/183151.shtml.

5 “there is not a young man now living in the U.S. who will not die a Unitarian.” — “Letter to Benjamin Waterhouse” (June 26, 1822), available at http://retirementseries.dataformat.com/Document.aspx?doc=150954873. (For the larger online archive, see http://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/papers).

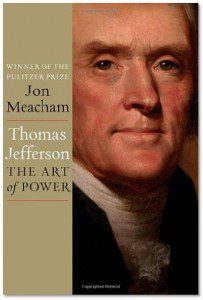

6 Unless otherwise indicated, parenthetical citations refer to Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (2012).

7 For the Black Friday articles, see:

- http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/23/san-antonio-man-pulls-gun-on-line-cutting-sears-black-friday-shoppers_n_2177293.html.

- http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/23/man-stab-kmart-customers-line-black-friday_n_2178898.html

- http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/23/walmart-strike-black-friday_n_2177784.html.

8 For more background on the history of the “Triple Bottom Line,” visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triple_bottom_line.

9 “If the middle class’s ceiling is $250,000” — Steve Thorngate, “Defining the middle” The rhetoric and reality of class” (October 16, 2012), available at http://www.christiancentury.org/article/2012-10/defining-middle. For the source of the chart, see Catherine Rampell, “Defining Middle Class” (September 14, 2012), available at http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/defining-middle-class.

10 Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton, “Don’t Indulge. Be Happy.” (July 7, 2012), available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/08/opinion/sunday/dont-indulge-be-happy.html?pagewanted=all.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg) .

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles/index.shtml