Laila Ibrahim, the Director of Children and Family Ministries at the First Unitarian Church of Oakland, California testifies that even the best, healthiest, most empowering communities are also messy, imperfect, and flawed:

I have been going to the same church for a very long time. For nearly thirty years most Sundays I have walked through our beautiful redwood doors. In all those years I have filled a variety of leadership positions, from [teaching the “Our Whole Lives” Sexuality curriculum] to Board President, usher coordinator to stewardship co-chair. And in all those years my congregation has had ample opportunity to disappoint me.

I am disappointed when people don’t think my justice project is the one we should collectively work on; I am disappointed when people want different music than I do; I am disappointed that we don’t all agree that our Children’s Ministry is the most important priority in the church; I am disappointed that people don’t give enough time, talent, or treasure to the church as I do. I am disappointed…well, you get the idea….

Two or three times over the years, I have been so disappointed that I seriously questioned remaining in my congregation. On those occasions, I have though, [screw] it. I can just stop going to church for a while or…forever. But staying away has never helped me through such times. Rather, coming in closer, telling people about my spiritual crisis — listening, sharing, caring, and worshipping have helped me….

Because we are not in church to be with people who want to sing the same music, or rally for the same cause, or attend the same retreats. We are in church to learn to love better…. We disagree, we annoy, we flake out on one another. And we worship, we support, we hold, and we affirm one another…. This is really only one choice: between imperfect community and no community. Again and again, we are all called to choose to commit ourselves to building a more just, more diverse, and yet ever messy and imperfect beloved community.

Underneath this insight is the truth that all communities are messy and imperfect because they are comprised of messy and imperfect human beings — like all of us.

The trouble with demanding perfection from ourselves or others is that old adage, “Wherever you go, there you are.” Now, certainly it is the case that some individuals and communities are more oppressive and more toxic than others. And we should seek out and help build healthier and more empowering systems in whatever communities we join. But, again, “wherever we go, there we are” with all our “baggage,” flaws, and imperfections. As Anne Lamott likes to joke, “My mind is like a bad neighborhood I try not to go into it alone.”

And whenever I take a step back and pause long enough to reflect, it’s clear to me that I don’t even know what it would mean to be a perfect person, living a perfect life, as part of a perfect community. But I still get caught up fairly often in the perfection trap. Perfection: “without flaws or defects.” Take one step back, and you have to ask, “Perfect according to whom? One person’s perception of flawless is another person’s idea of a serious defect. To use only a few mundane examples, is perfection the still, majestic grandeur of the mountains or the shifting sand and crashing waves of an ocean view? (Marriages have ended over less.) Is perfection big or small, fast or slow, short-term or long-term? In almost any category, one person’s flawless is another’s defect.

There is no universal, unchanging standard of perfection, and that realization can be liberating. From the ancient insights of Buddha to modern quantum physics we have increasingly come to see that there is no universal, permanent anything that could even be an unchanging standard of perfection. Reality is more of a verb than a noun. Everything is in process: moving, flowing, evolving. And, as Buddha taught 2,500 years ago, when we demand unchanging perfection from a universe that is always already in the process of changing, we create suffering for ourselves.

As George Eliot wrote in her novel Middlemarch, “the mistakes that we male and female mortals make when we have our own way might fairly raise some wonder that we are so fond of it.” There are likely many other wise insights in Middlemarch, which some critics have called the greatest English-language novel ever written, but I wouldn’t know because I have never been able to motivate myself to finish it, despite having started it on at least three separate occasions. In my mind’s eye of perfection, I’m the sort of person who, of course, has read Middlemarch. And I am if you count reading the first third three times!

Slogans such as “Seize the Day!” or “What are you going to do with your one wild and precious life?” can sometimes be incredibly inspiring. But there are other times when these “Just do it” slogans can also feel impossibly demanding to sustain and frankly exhausting. Sometimes instead of seizing the day, I need to just receive the day…on my sofa…in my pajamas. (Can I get an Amen?!)

In graduate school — that time which can be the height of idealized, theoretical images of what is possible in life (because way up in the ivory tower you can become so far removed from the reality of everyday life) — during that time I remember reading a self-help book written from the perspective of Ken Wilber’s Integral philosophy called Integral Life Practice: A 21st-Century Blueprint for Physical Health, Emotional Balance, Mental Clarity, and Spiritual Awakening. Part of the book’s argument was that to fully actualize our potential and become our best selves — what Oprah calls “Your best life now” — that you need to always be working on at least the four areas in the subtitle: physical fitness, emotional wellness, lifelong learning, and spiritual growth. I am drawn to that idea in theory, but what I found in practice is that constantly trying to work on all those aspects of yourself is exhausting. And especially if you are really working on one area, you may well have to let go for a while of some of the other areas. If you’re pushing the envelope in one area — training for a long run, seeking therapy for the first time (or the first time in many years), enrolling in a new degree program, committing to a meditation or yoga routine, or experiencing a major transition or upheaval in your life — then maybe it’s time to let yourself coast a bit in some other areas of your life.

I’ve been reflecting on this dynamic a fair amount recently because this past week I finished as a participant the UU Ministers Association’s pilot program on Ministerial Wellness called “Choose Health.” And on one hand, I agree with the need to take time off and set aside time for exercise, study, meditation, and family. On the other hand, I feel the pull of how much the congregation I serve as minister is accomplishing and the excitement that we have not even begun to reach the full potential of what we can do together. The shadow side is that perfect image of what we can become as a congregation can also be oppressive. We UUs have such inspirational goals, but those same goals can inhibit us from resting so that we can go the long-haul or from celebrating the small victories along the way. Consider our Sixth Principle: “The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all.” I couldn’t agree more in theory, but I also can’t imagine that we’ll get there in my lifetime.

I want excellence from myself, for my congregation, and for our world. I want, in the words of our Unitarian forbear Henry David Thoreau, to “live deliberately…and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived…. to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” But I am also learning the liberation that can come from confessing my limitations and imperfections.

Along these lines, Peter Rollins, likes to tell the story that,

There was once a man who had been shipwrecked on an uninhabited desert island. There he lived alone for ten years before finally being rescued by a passing aircraft. Before leaving the island, one of the rescuers asked if they could see where the man had lived during his time on the island, and so he brought the small group to a clearing where there were three buildings. Pointing to the first he said, “This was my home; I built it when I first moved here all those years ago,” “What about the building beside it?” asked one of the rescuers. “Oh that is where I would worship every week,” he replied.“And that building beside that?” “Don’t bring that up,” replied the man in an agitated tone. “That’s where I used to worship.”

Conflict and schism happen even when you are by yourself on a uninhabited desert island! Indeed, Rollins says that he has come to see our human desire for certainty, satisfaction, and perfection as addictions that we need to break, now that we know reality is always already in the process of evolving and changing — undercutting any permanent hope for certainty, satisfaction, and perfection. He writes:

You can’t be fulfilled; you can’t be made whole; you can’t find satisfaction. [You may experience them temporarily, but not permanently.] At first this can sound like anything but good news; however, once we are free from the oppression of the Idol, we find that embracing and loving life — with all its difficulties — offers a much deeper and richer form of joy” (86).

He continues in a related blog post:

The individual who is able to loose themselves from the notion that there is some ultimate purpose to their life frees themselves from the negative melancholy that comes with being unable to find that purpose (or the naïve optimism that comes from thinking that they will). The secret…is that there is no secret. Instead the challenge is to discover and deepen love. For love not only affirms the world, it produces a surplus in that joyful affirmation: acts that enact liberation.

What I hear Rollins saying is that if we demand permanent, perfect satisfaction from our life, we will be disappointed, potentially robbing ourselves of the opportunity to savor and celebrate the gifts of the life that we do have already: right here and now.

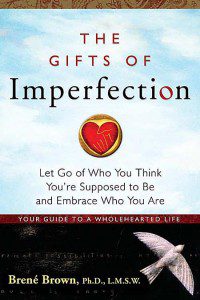

And in recent years one of the people who has taught me the most in this area is the research psychologist Dr. Brené  Brown, who studies fear, shame, and vulnerability. In her book The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are, she writes about collecting huge amounts of data about how human lives are shaped by the “struggle with shame and the fear of not being enough” as well as “the power of embracing imperfection and vulnerability.” She then began analyzing the data for common characteristics of people who were resilient in the face of adversity and who were living wholehearted life: “living and loving with their whole hearts.” Emerging out of that huge data set were some clear patterns:

Brown, who studies fear, shame, and vulnerability. In her book The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are, she writes about collecting huge amounts of data about how human lives are shaped by the “struggle with shame and the fear of not being enough” as well as “the power of embracing imperfection and vulnerability.” She then began analyzing the data for common characteristics of people who were resilient in the face of adversity and who were living wholehearted life: “living and loving with their whole hearts.” Emerging out of that huge data set were some clear patterns:

The Do column was brimming with words like worthiness, rest, play, trust, faith, intuition, hope, authenticity, love, belonging, joy, gratitude, and creativity. The Don’t column was dripping with words like perfection, numbing, certainty, exhaustion, self-sufficiency, being cool, fitting in, judgment, and scarcity. (x)

Now, I don’t know what your reaction is to that “Do” and “Don’t” list. But Brown confesses that her initial reaction was horror. She says, “I thought I’d find that Wholehearted people were just like me…: working hard, following the rules, doing it until I got it right, always trying to know myself better, raising my kids exactly by the books…” (xi). But Brown was horrified by the revelation that as a successful professional, she had been formed and rewarded for living almost exclusively by the list of how not to live a wholehearted life, by the list of how to increase the likelihood of reaching the end of your life with many regrets: “perfection, numbing, certainty, exhaustion, self-sufficiency, being cool, fitting in, judgment, and scarcity.” So, she packed up her research and hid it under her bed for a year-and-a-half (xii)!

When you pause and take a step back, you can often see that daily life is a constant reminder of our imperfections and limitations. We are constantly being invited to “let go of who we think we’re supposed to be and embrace who we are,” but often we’re like Brown and shove those invitations under the rug as quickly as possible. In Brown’s words, “The universe is not short on wake-up calls. We’re just quick to hit the snooze button” (xiii).

The UU First Principle affirms, “The inherent worth and dignity of every person.” But often it can be easier for many of us to fight for the rights and recognition of a marginalized group than to fully embrace the inherent worth and dignity of all those hidden parts of our own self: all those imperfect parts that we hope we are hiding from others. As the old saying goes, “Too often we compare our insides to others’ outsides, and we feel inadequate.”

Brown writes, “The greatest challenge for most of us is believing that we are worthy now, right this minute.”

Not I’ll be worthy when I lose twenty pounds, if I can get pregnant, or stay sober. Not I’ll be worthy if everyone thinks I’m a good parent, when I can make a living selling my art, if I can hold my marriage together, when I make partner, when my parents finally approve, if he [or she] calls back…, or when I can do it all and look like I’m not even trying. (24)

On the other side of a lot a research and some important work in therapy during that year-and-a-half in which she had hidden her research under the bed, Brown says that she’s come to be “a recovering perfectionist and an aspiring good-enoughist.” That doesn’t mean that we should stop pursuing excellence. But when you embrace your inherent worth and dignity, then your motivation changes in a vital way. Brown puts it this way, “Healthy striving is self-focused — How can I improve? Perfectionism is other-focused — What will they think?” (56). The middle way is perhaps neither the narcissism of exclusive self-interest nor the self-deprecation of acting only for others, but instead knowing your limits and seeking the next best step for both yourself and others.

Leonard Cohen, in the chorus of his song “Anthem,” says that all any of us can ultimately do is “Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in. That’s how the light gets in. That’s how the light gets in.”

Where are the cracks and imperfections in your life?

How might those places of seeming weakness paradoxically be the most powerful invitations you will ever have in this life to “let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are,” to let go of our culture’s addiction to certainty and the myth of permanent satisfaction — and instead to savor and celebrate the gifts of the life that already have: right here and now.

I will conclude by offering you this blessing from one of my favorite liturgists Jan Richardson. In this life, we all have our different struggles, gifts, and graces:

May you have the vision to recognize the door that is yours,

the Courage to open it,

and the wisdom to walk through. (47)

May it be so, and blessed be.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles