Yesterday I posted about “Reading the Same Text Differently with Jews & Christians Read” about the ways Christians have often appropriated Jewish scripture in a way that does not fully appreciate the ways that Jews understand their own texts in very differently. In this post, I am turning the tables to consider Jewish readings of Christian scripture — in particular, Jesus’ parables.

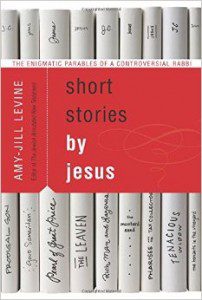

The inspiration for this post is a new book, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi by Amy-Jill Levine, who is a Jewish New Testament scholar at Vanderbilt University. She describes herself as a “Yankee Jewish feminist who teaches in a predominantly Christian divinity school in the buckle of the Bible Belt.” Levine’s book invites us into: “an act of listening anew, of imagining what the parables would have sounded like to people who have no idea that Jesus will be proclaimed Son of God by millions, no idea even that he will be crucified by Rome. What would they hear a Jewish storyteller telling them?” (23). I would say further that we should seek to hear the parables as Rabbi Jesus himself intended them because the historical Jesus also had no idea that he would one day be declared co-equal with God, an idea he would have found blasphemous.

The inspiration for this post is a new book, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi by Amy-Jill Levine, who is a Jewish New Testament scholar at Vanderbilt University. She describes herself as a “Yankee Jewish feminist who teaches in a predominantly Christian divinity school in the buckle of the Bible Belt.” Levine’s book invites us into: “an act of listening anew, of imagining what the parables would have sounded like to people who have no idea that Jesus will be proclaimed Son of God by millions, no idea even that he will be crucified by Rome. What would they hear a Jewish storyteller telling them?” (23). I would say further that we should seek to hear the parables as Rabbi Jesus himself intended them because the historical Jesus also had no idea that he would one day be declared co-equal with God, an idea he would have found blasphemous.

To use an classic Unitarian Universalist slogan, I hear this view as inviting us to see the parables as about “deeds not creeds.” Many traditional interpretations of the parables see these stories as all about how great God is. But a “deeds not creeds” point of view invites to consider how Rabbi Jesus is inviting us not just to believe differently, but to act differently.

In that spirit, consider this parable, recorded for us in the twentieth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, with an eye toward “deeds not creeds.” Be attentive for how is this story might be inviting us to change not only our beliefs, but also how we treat one another?

1 For the [“Beloved Community”] is like a landowner who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard. 2 After agreeing with the laborers for the usual daily wage, he sent them into his vineyard. 3 When he went out about nine o’clock, he saw others in the marketplace [“wanting work, but not able to find it”]; 4 and he said to them, “You also go into the vineyard, and I will pay you whatever is right.” So they went. 5 When he went out again about noon and about three o’clock, he did the same. 6 And about five o’clock he went out and found others standing around; and he said to them, “Why are you standing here wanting work, but not able to find it all day?” 7 They said to him, “Because no one has hired us.” He said to them, “You also go into the vineyard.” 8 When evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his manager, “Call the laborers and give them their pay, beginning with the last and then going to the first.” 9 When those hired about five o’clock came, each of them received the usual daily wage. 10 Now when the first came, they thought they would receive more; but each of them also received the usual daily wage. 11 And when they received it, they grumbled against the landowner, 12 saying, “These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.” 13 But he replied to one of them, “Friend, I am doing you no wrong; did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage? 14 Take what belongs to you and go; I choose to give to this last the same as I give to you. 15 Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?” (208)

One traditional interpretation of this passage (“The Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard”) is that God is the landowner, the vineyard is our work in this world, and the payment at the end of the day — metaphorically, at the end of our lives — is whom the landowner God will reward with heaven. And read through an “otherworldly” lens, this parable can be seen as not about us humans, but instead about God. In that view, the parable’s “lesson” is that God is more generous than we expect or deserve, and chooses to let people into heaven both those who have done only a tiny bit of good at the end of their lives as well as those who have done good their whole lives. In the words of the parable, “These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.”

But what if we take up Amy-Jill Levine’s challenge to consider how this story would have been heard by impoverished Jewish peasants two thousand years ago. What if we listen for what Rabbi Jesus may have saying not about God, but about us, about this world, and this life? What if this parable is not about our “creeds” (what we believe about God or the afterlife), but about our deeds right here and now on this earth.

What if instead of calling this story the “Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard,” we consider some of the alternative titles that have been proposed:

“The Parable of the Complaining Day Laborers”

“The Parable of the Surprising Salaries”

“The Parable of the Humane Capitalist”

“The Conscientious Boss,”

“The Last Hired Are the First Paid”

“How to Prevent the Peasants from Unionizing”

“Debating a Fair Wage”

“Lessons for Both Management and Employees”

“The Parable of the Affirmative Action Employer” (199, 201)

Now, before proceeding much farther, I mentioned earlier that it illuminating to explore the ways that the Christian Scriptures recapitulate the Hebrew Scriptures. In this case, it is likely that Jesus’ familiarity with a passage from 1 Samuel inspired this parable (Davies and Allison, 330). A thousand years before Jesus, King David ruled a United Kingdom of Israel. And 1 Samuel 30:10 tells story — “The Parable of Equal Compensation for Soldiers,” if you will — in which, “David went on with the pursuit [of the Amalekite army], he and four hundred men; two hundred stayed behind, too exhausted to cross the [valley].” Ten verses later, when they returned victorious, we read in verse 21 that, “When David drew near to the people he saluted them.” But, in contrast to David’s generous greeting, the foot soldiers who had been in battle declared, ‘Because they did not go with us, we will not give them any of the spoil that we have recovered….’”

But David rebukes them in a way that presages Jesus’ parable saying, “For the share of the one who goes down into the battle shall be the same as the share of the one who stays by the baggage; they shall share alike.” Verse 25 goes on to say, “From that day forward he made it a statute and an ordinance for Israel; it continues to the present day.”

And a millennia later, when Jesus is one among quite a few people who are declared to be a potential a “messiah.” Part of what being declared a messiah meant is that Jesus is hoped to turn out to be a king like David, who will restore the so-called “Golden Age” of Israel as it was under the United Monarchy. Of course, it’s a lot more complicated than that with both David and Jesus — not for the least of which reasons that David attempted to cover up his affair with Bathsheba by having her husband killed. (Rarely were so-called Golden Ages as glorious as they are sometimes nostalgically remembered to be.)

Returning focus to our parable, when those day labors hired at 5:00 p.m. received a full day’s wage for only working one hour, those who were hired at dawn (and had worked a hard, 12-hour day) leapt to the conclusion that they must be in for an equivalent surprise of much more than “the usual daily wage.” Shouldn’t they receive four times more those hired last since they had worked four times as many hours?

But hearing their grumbling, you may recall that the landowner contends, “Friend, I am doing you no wrong…. I choose to give to this last the same as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?’” And when you read this parable from the perspective of a call to “love the hell out of this world,” it is important to consider that — both then and now — the day laborers picked first at dawn are the youngest, strongest, healthiest workers. For these workers in their prime, the landowner paid “the usual daily wage.” It’s basic economics: supply and demand. To enlist those workers in greatest demand, you have to pay the standard rate. Those left behind were the older, weaker workers.

But, “When the landowner went out about nine o’clock, he saw others standing wanting work, but not able to find it in the marketplace.” The landowner had hired all the workers he needed for the day three hours earlier at dawn. And perhaps he assumed other landowners would hire the remaining workers. But upon seeing workers still standing around three hours later hoping to be hired, he said, “You also go into the vineyard, and I will pay you whatever is right.” Notice that he doesn’t agree with these less desirable laborers for the usual daily wage as he had with his first round draft picks. Nor do the laborers haggle with him over a rate. They are eager to be paid “whatever the landowner deems right” when the alternative is returning home to their families with no pay at all.

When the landowner “went out again about noon and about three o’clock, he did the same.” Most shockingly, one hour before the end of the 12-hour workday, “he went out and found others standing around; and he said to them, ‘Why are you standing here wanting work, but not able to find it all day?’ They said to him, ‘Because no one has hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You also go into the vineyard.’” So perhaps an even more controversial title for this story might be “The Parable that All People Who Want to Work Should Be Given a Job and Paid a Generous Wage.” After all, contrary what sometimes seems to be popular opinion, the Christian Scriptures are about “What Would Jesus Do?” not “What Would Ayn Rand Do?”

From a perspective of “full employment,” Jesus’ parable invites us not only to praise the “Generous Landowner,” but also to reflect on the plight of the day laborers. Yes, the landowner could be called, in our political-speak, a “Job Creator.” He did generously create jobs that would not otherwise have existed that day for a host of workers. But it is important to point out that “the usual daily wage” for manual labor would have been “The denarius, a Roman silver coin, that had approximately the same value as the Greek drachma….” Rabbinical sources tell us that rate was actually “neither generous nor miserly” (Davies and Allison, 309, 330). That point undercuts the usual interpretation of this story as primarily a vehicle to praise generous landowners. Scholars tell us that the usual daily wage paid “perhaps enough for a subsistence existence” (Carter, 296). That’s a low minimum wage, not a sustainable “Living Wage.”

Turning the tables, perhaps what those full-day, hard workers were excited about — upon seeing the latecomers get the usual subsistence wage — was that maybe for once they were going to get a “Living Wage” that could give them a little breathing room financially. That insight gives us ears to hear the landowner’s words not only as well-intentioned and lined with some generosity, but also as unintentionally paternalistic, condescending, and oblivious to the serious day-to-day struggles of all his day laborers. So, on one hand, yes, he is generous for paying so many extra people a minimum wage. On the other hand, he has paid none of them a Living Wage. And by hiring day laborers, he is still keeping all the power to himself. He is not giving any of the workers the security of a long-term contract or benefits.

Remember as well that Jesus himself was an itinerant Jewish peasant, and it is quite possible that the original audience for this parable would have been precisely those less-desirable day laborers who were standing around at 9:00, Noon, 3:00, or 5:00 hoping to be hired; they are the ones out of work with the time to listen to an itinerant rabbi storyteller. Perhaps in the audience as well were landowners who after hiring the needed day laborers at dawn had leisure time for the rest of the day to listen to itinerant rabbis.

Jesus’ parables, when stripped of later “other-worldly” interpretations that were laid onto them, reveal the original radical stories of a traveling Jewish rabbi reinterpreting the Hebrew prophetic tradition to condemn inequality and call for justice in his own day. In the words of Amy-Jill Levine:

the parable does not promote egalitarianism; instead, it encourages householders to support laborers, all of them. More than just aiding those at the doorstep, those who have should seek out those who need. If the householder can afford it, he [or she] should continue to put others on the payroll, pay them a living wage (even if they cannot put in a full day’s work), and so allow them to feed their families while keeping their dignity intact. The point is practical, it is edgy…. Jesus is neither a Marxist not a capitalist. Rather, he is both an idealist and a pragmatist. His focus is…[the] “responsibility of the rich.” (218-219)

May we work for a world, not in which everyone is equal — whatever that would even mean given how different we all are— but for a world in which everyone who wants to work is paid at least a living wage and in which everyone has a simple, decent place to live.

But in addition to such large goals, for now, in the coming days and weeks, I invite you to consider what do you have in abundance?

Out of that abundance, to whom might you be called to seek out and practice abundant generosity?

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles