Richard Linklater is the director of such contemporary cinema classics as Dazed and Confused (about a last day of high school in the 1970s), School of Rock (about Jack Black inspiring a classroom of fourth graders to enter a Battle of the Bands), and the Before Trilogy (about the relationship over time between Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy). Of those films, the Before Trilogy (Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight) is where we first began to see Linklater’s willingness to risk playing the long game.

Before Sunrise came out in 1995; it’s about a young American man (Jesse) and a young French woman (Céline ) meeting randomly and spending one night talking as they walk through Vienna. The only time they have together is “before sunrise.” Here’s the twist: the next two installments (Before Sunset in 2004 and Before Midnight in 2013) were filmed and released at nine-year intervals with the same two actors, who are themselves nine years older, playing the same characters, and with the details of the plot influenced by their actual lives during the previous nine years. Barring any unforeseen tragedies in the actual lives of Linklater, Hawke, and Delphy, I suspect we’ll see a fourth installment in the “Before” films in 2022. In the meantime, if you haven’t seen the first three, I recommend them. The point is that Linklater is interested in coming of age, ordinary life, and how we humans are swept up in the ongoing flow of time.

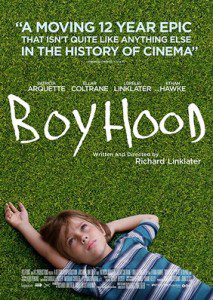

In 2014, Linklater released the film Boyhood, which has received to date his greatest critical acclaim. In this film we see Linklater taking an even greater risk on the long game. In 2002, two years prior to filming the second installment in the Before series, Linklater cast six-year-old Ellar Coltrane as Mason, the star of a film that had the working title 12 Years, which was changed to Boyhood to avoid confusion with the film 12 Years a Slave. Linklater’s achievement is a powerful example of the old saying that, “We often overestimate what we can accomplish in a day, and underestimate what we can do in a decade.”

In 2014, Linklater released the film Boyhood, which has received to date his greatest critical acclaim. In this film we see Linklater taking an even greater risk on the long game. In 2002, two years prior to filming the second installment in the Before series, Linklater cast six-year-old Ellar Coltrane as Mason, the star of a film that had the working title 12 Years, which was changed to Boyhood to avoid confusion with the film 12 Years a Slave. Linklater’s achievement is a powerful example of the old saying that, “We often overestimate what we can accomplish in a day, and underestimate what we can do in a decade.”

The cast came together once a year for twelve years to create a film whose plot evolved over time. And the film itself is those twelve segments edited together, showing annual scenes from Mason’s life from first grade through his first day of college. And as with the Before Trilogy, Boyhood is a profound meditation on the passage of time. As the writer of Ecclesiastes says, “Time and chance happen to us all.”

Linklater cast his own young daughter as the co-star. And as she became a teenager, she once asked him, “Dad, can my character, like, die?” to which Linklater replied, “No, that would be a little dramatic for this movie!” — which points to the heart of this film’s brilliance. Boyhood is not about major “train wreck” experiences, which can happen in real life. There are plenty of movies that cram an incredible amount of melodrama into two hours. Instead, Boyhood is more about the triumphs and travails of everyday life: coming of age, parenting, and surviving adulthood.

In that spirit, I want to reflect on the spirituality of the ordinary. It’s no coincidence that another of Linklater’s longterm future projects, one he has been working on for more than a decade, is about the Transcendentalists, some of our nineteenth-century forebears of my own tradition of Unitarian Universalism. Emerson, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and their many Transcendentalist contemporaries powerfully challenged the religious establishment of their day with the insight that spiritual depth is as accessible here, now, and in nature as it was deemed to be (in the antiquated notions of the past) only in officially-sanctioned “holy places.” The Transcendentalists taught us that, “Everything Is Holy Now.”

In contrast, the history of spirituality has often been an emphasis that the sacred is only found in certain people (like priests), only in certain holy places (that are often cordoned off), and only at certain times (special holy days). And the history of most spiritual traditions have emphasized the spiritual superiority of a professional clergy class — the Christian or Buddhist monks, Hindu gurus, Jewish rabbis who spent all day in Torah study — and who were thus allegedly able to achieve holiness on a level unreachable by us regular folk.

While we should recognize and honor historically-sacred times and places, it is also vital to claim the sacredness of ordinary life, and of all times and places. On one hand, mountain-top monastics who spend all their time in a cloistered retreat setting do often have valuable contemplative insights to share that can benefit those of us who find ourselves “crazy busy” more often than we would like. On the other hand, many regular folks have been wounded over the years by monastics who, with little or no experience in the secular world have nevertheless felt it their duty to issue decrees “from on high” about how all humanity should live. These decrees are often unrealistic for all except those living in retreat settings with no family obligations—and then only with financial support from the freewill donations of all the ordinary people the priests are so quick to criticize for being unspiritual! Indeed, the more difficult and important spiritual challenge of our time may be cultivating a greater appreciation for the sacred in the workplace, in relationships, and in activism for social change.

For example, in Buddhism, one of the gold standards is going on a three-year retreat. And as powerful as those experiences are, for most people, a three-year retreat will never be even close to a realistic option. Instead, the far more important task is integrating the wisdom of the world’s religions into your everyday life. Whatever your path, I invite you to consider that more important than your experience during spiritual practice is the fruit of that practice in the rest of your life.

Of course I am interested in your experiences during your spiritual practices, but I am equally interested in whether your spiritual practice helps you feel more connected to yourself, to other people, and to the world throughout the day. Does your spiritual practice help you become a better, more-grounded co-worker, partner, and parent? The point is learning to transform our experience of the ordinary. You can know that you are on the right track in your spiritual practice if, in words from the Christian tradition, you increasingly see more “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control” in your life, or, in words from the Buddhist tradition—whether you see more daily “generosity, renunciation, wisdom, strength, effort, truthfulness, determination, loving-kindness, equanimity.”

Quotidian spirituality is about integrating the wisdom of the world’s religions into the “every day, commonplace, and ordinary.” As the spiritual teacher Henri Nouwen writes in a paragraph that seems freshly relevant with the Trump Administration,

Not too long ago a priest told me that he canceled his subscription to The New York Times because he felt that the endless stories about war, crime, power games and political manipulation only disturbed his mind and heart, and prevented him from meditation and prayer. That is a sad story because it suggests that only by denying the world can you live in it, that only by surrounding yourself by an artificial, self-induced quietude can you live a spiritual life. A real spiritual life does exactly the opposite: it makes us so alert and aware of the world around us, that all that is and happens becomes part of our contemplation and meditation and invites us to a free and fearless response.

In a world filled with fear-mongering and demagoguery, Nouwen reminds us of the hope that, through spiritual practice, we might become more contemplative, grounded, and centered such that whatever comes, we might bring a “free and fearless response.”

At the same time, I do not intend to imply that the point is a one-time act of heroism. Rather, the invitation is to ever more fully see the sacred in the ordinary. As Kathleen Norris writes in her book The Quotidian Mysteries, “The ordinary activities I find more compatible with contemplation are walking, baking bread, and doing laundry” (15). Or as the eighth-century Muslim Sufi mystic Rabia of Basra wrote,

It helps, putting my hands on a pot,

on a broom, or in a washing pail.

I tried painting, but it was easier to fly

slicing potatoes.

Along these lines, one of my favorite books on ordinary spirituality is Jack Kornfield’s After the Ecstasy, the Laundry. Religion is as much about the mundane as the mountain-top. In Kornfield’s words: “We all know that after the honeymoon comes the marriage, after the election comes the hard task of governance. In spiritual life it is the same: After the ecstasy, comes the laundry” (xiii). And it is understandable to want a great honeymoon, to win an election, and to have a powerful spiritual epiphany. But:

- Who cares about a great honeymoon if the marriage falls apart?

- Who cares about a winning an election if the governing is corrupt or inept?

- Who cares about a passing moment of spiritual rapture if you do not integrate those insights into treating others (and yourself) with more humility, compassion, and kindness throughout the day?

The mountaintop moments are always fleeting. The invitation is to see the ordinary moments as sacred too. As we reflect on our ordinary lives, poet Jean Valentine reminds us, “Blessed are they who remember that what they now have they once longed for.”

To share only one of the many interviews from Kornfield’s book, one woman says:

As a young Catholic I was inspired by the saints. I had always wanted to do things like work with Mother Teresa in India, but most of my life has not been so glamorous. After college, I became a teacher in an elementary school. And then my mother had a stroke and I had to drop out of teaching and help her for two years: bathe her, care for her bedsores, cook, pay the bills, run the house. At times I wanted to complete these responsibilities and get back to my spiritual life. Then one morning it dawned on me — I was doing the work of Mother Theresa, and I was doing it in my own home” (229)

That’s real spirituality: the ordinary spirituality that is equally (or more) demanding, challenging, and profound than anything you will every experience at a mountaintop retreat.

For now, I will conclude with some lyrics from the singer-songwriter Carrie Newcomer:

I believe in jars of jelly put up by careful hands,

I believe most folks are doing about the best they can….

I believe in a good long letter written on real paper and with real pen,

I believe in the ones I love and know I’ll never see again,

I believe in the kindness of strangers and the comfort of old friends…

And I know that I get scared some times

But all I need is here….

All I know is I can’t help but see

All of this as so very holy.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles