Lorraine Hansberry died in 1965 at the far too young age of thirty-four. In those few decades, however, she nevertheless became “the first Black woman to have her play produced on Broadway and the first Black winner of the prestigious Drama Critics’ Circle Award. That first play, A Raisin in the Sun, is the most widely produced and read play by a Black American woman.” When she won that Drama Critics’s Award at the age of twenty-nine, she was also the youngest playwright ever to do so (1).

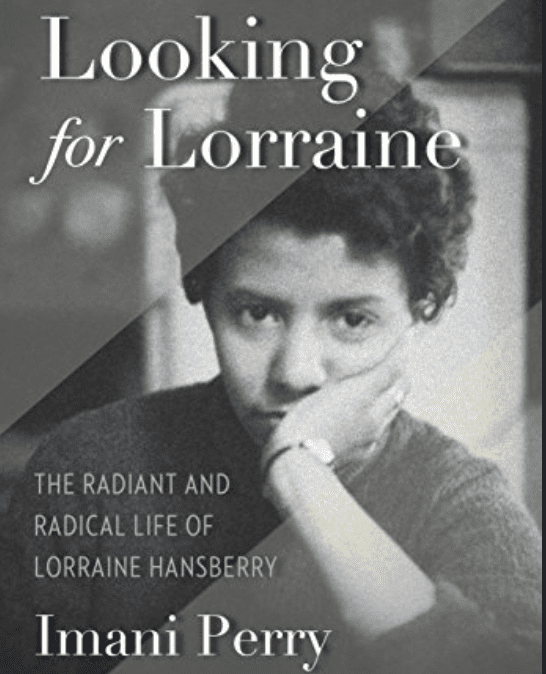

And as impressive as those accolades are, she was also much more. In the words of Imani Perry, who has published an incredible recent biography titled Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Beacon Press, 2018):

She was a Black lesbian woman born into the established Black middle class who became a Greenwich Village bohemian leftist married to a man, a Jewish communist songwriter. She cast her lot with the working classes and became a wildly famous writer. She drank too much, died early of cancer, loved some wonderful women, and yet lived with an unrelenting loneliness. She was intoxicated by beauty and enraged by injustice. (2-3)

I have been wanting to read this book ever since The New York Times named it as one of their “100 Most Notable Books of 2018.” If you prefer to watch instead of read, I also highly recommend the 2017 documentary Sighted Eyes / Feeling Heart about Hansberry, which is available through Kanopy. The title comes from a quote from Hansberry that, “One cannot live with sighted eyes and feeling heart and not know or react to the miseries that afflict this world.”

I have been wanting to read this book ever since The New York Times named it as one of their “100 Most Notable Books of 2018.” If you prefer to watch instead of read, I also highly recommend the 2017 documentary Sighted Eyes / Feeling Heart about Hansberry, which is available through Kanopy. The title comes from a quote from Hansberry that, “One cannot live with sighted eyes and feeling heart and not know or react to the miseries that afflict this world.”

For such a time as this, I find Hansberry’s life and writings to be a both a comfort and a challenge for continuing the struggle for social justice. Hansberry wanted to change the world: to build the beloved community, to co-create the world we dream about, to turn our dreams into deeds. To tell you some of how she came to live such a “radiant and radical life,” allow me to start at the beginning.

She was born into an impressive family. Hansberry’s paternal grandfather was a history professor at Alcorn College (now Alcorn State University) in Mississippi. Alcorn was founded in 1871 as the first black land grant college in the country. Her father, in turn, graduated from Alcorn and became a successful real estate entrepreneur in Chicago. Her mother was a teacher and significantly involved in local politics. Her uncle William Hansberry graduated from Harvard, then taught at Howard University, and is known as the father of African Studies. Surrounded by such a family, let’s just say that there were high expectations of both Lorraine and her siblings (4).

Lorraine Hansberry was born in 1930 in Chicago, the last of four children. And given what we know about the trajectory of her life, it seems fitting that her mother gave birth to her in “the first Black owned and operated hospital in the nation” (9). Keep in mind, however, that being born in 1930 meant that the first decade of her life was during the Great Depression, which stretched from 1929 (the year before she was born) until the late 1930s.

That severe worldwide economic depression was the context for one of her earliest lessons in class consciousness. Her parents bought her a white, rabbit-fur coat and forced her to wear it to school. From their perspective, the coat was a celebration of their hard work and success, but for Lorraine it meant getting beat up by her classmates, whose families had far fewer resources (11).

And although her resistance to wearing the cost was an early sign of her developing much more radical politics than her family of origin, I should hasten to add that her parents were activists in significant ways as well. In particular, in 1937 (when Lorraine turned seven years old), her father purchased a building in a section of town with a racially restrictive covenant (12). This bold move for greater racial equality developed into a years-long court battle, and the family become a target for hate crimes. The scariest moment was when someone threw a chunk of cement through their window barely missing Lorraine’s head. She was seven years old at the time (13).

The struggle over this property went all the way to the United States Supreme Court. And in 1940, when Lorraine was ten years old, the highest court in our land ruled in her father’s favor in the case of Hansberry v. Lee. Those of you familiar with her play Raisin in the Sun will see how her real life experience helped inspire that play about a black family buying a home in a white neighborhood.

Although the family won the case, her father was disillusioned that they focused on a technicality: the “racially restrictive covenant had been improperly executed as a contract” and was therefore invalid (17). It would not be until 1948, another eight years later, that the Supreme Court would do the right thing and declare that all racially exclusionary covenants are “unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment and were therefore legally unenforceable” (Shelley v. Kraemer).

Tragically, her father would not live long enough to witness those results. In 1946, when Lorraine was only fifteen years old, her father died of a brain aneurysm while on a trip to Mexico. And although Lorraine described her father as a “real American type American,” who believed in fighting for civil rights “the respectable way,” it turns out that he was in Mexico as part of a larger plan to move their family there (17). He had “bitterly decided there was little hope for a racially integrated and just life in the United States” (22). Her father’s death was devastating, and his influence—“honoring him, arguing with him, thinking about the aftermath of his death—is all over her work as a writer” (23).

And before I move away from her childhood, I should also mention that I am always fascinated when I learn of people who become a world-class success while having a lackluster academic record. In Lorraine’s case, her high school transcript shows a “C in stage design, a C in contemporary literature, and a D in theater” (20). If only those teachers had known!

Regardless of these mediocre grades, her family, who had seen evidence of her creativity and brilliance at various points, expected her to attend a historically Black college or university. Instead, we witness the first major turning point of Lorraine charting a different path. She chose the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where “only a smattering of Black students had enrolled since 1875” (26).

In 1949, while at U Madison, many of her fellow students were electing to study abroad in Europe. She chose instead to spend the summer at an art program in Mexico, the country where her father had died (35). This international immersion in an artist enclave shifted something within Hansberry, and upon her return to the university, she found herself disillusioned with formal academic study. She found herself on academic probation after the fall semester, then dropped out early in the spring (35). Soon she was on her way to the next chapter in her life: New York City (42).

That fall instead of starting a new semester in the ivory tower, she was celebrating her first publication, a poem titled “Flag from a Kitchenette Window.” That poem has been interpreted as a “sparse indictment of American militarism and hypocritical proclamations of liberty in the face of Jim Crow: an ironic commentary on Memorial Day” (44).

In her early years in New York City, she could also be found frequently at social justice actions and volunteering with political campaigns for left-wing candidates (50). Indeed, she met her eventual husband, Bobby Nemiroff, at a racial justice protest at New York University, where he was in graduate school (6). They were married in 1954, the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racially segregated schools are “inherently unequal” and therefore violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (65). Although that decision was good news, Lorraine’s dream for this country involved much deeper change than Brown represented (67).

I should also be sure to include that Hansberry lived quite a radical life as a lesbian. (Keep in mind that she died quite a few years before the Stonewall Uprising of 1969.) And although her romantic connection ended with Bobby, they remained close, and he continued to be one of her strongest advocates for the rest of his life. I find it particularly poignant that, “Robert, his second wife, and her daughter left neatly maintained folders with her writings on lesbian themes” as part of preserving and promoting her legacy (83).

Among Lorraine’s lovers was Molly Malone Cook, who at that time was a photographer for the Village Voice. Later Cook moved to Massachusetts, where she would be the partner for more than four decades of the beloved poet Mary Oliver (91).

Lorraine was also close friends with the singer and activist Nina Simone (1933-2003), as well as the writer and activist James Baldwin (1924 – 1987). Simone said of Lorraine that, “We never talked about men or clothes or other such inconsequential things when we got together. It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution—real girls’ talk” (117). Baldwin said of her that, “I would often stagger down her stairs as the sun came up, usually in the middle of a paragraph and always in the middle of a laugh. That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister and my comrade” (121).

Although Hansberry supported the work of The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., she also supported more radical approaches to racial justice, which resulted in the FBI surveilling her at various times. For instance, in a 1963 talk she delivered almost a year before Malcolm X’s famous “by any means necessary” speech, Lorraine said:

Negroes must concern themselves with every single means of struggle: legal, illegal, passive, active, violent and non-violent. That they must harass, debate, petition, give money to court struggles, sit-in, lie-down, strike, boycott, sing hymns, pray on steps—and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through their communities. The acceptance of our present condition is the only form of extremism which discredits us before our children. (169).

Pancreatic cancer however, cut her life tragically short. She died about a year-and-a-half after that talk in January of 1965 at the age of 34 (177).

Even in those few decades, she left a powerful impression on many. Her funeral ended up being held on the day of a blizzard, but more than seven hundred people still showed up to pay their respects (190). Among those in the crowd was Malcolm X, who at that time was in hiding due to death threats. Indeed, he would be murdered three weeks later on a day that was also Nina Simone’s birthday (196). (What a measure of a life: Live in such a way that such a fierce activist for justice as Malcolm X would be willing to risk his life to pay his respects to you.)

For Hansberry’s funeral, James Baldwin wrote these words:

Lorraine and I were very good friends and I am going to miss her. Grief is very private. I really can’t talk about her or what she meant to me. We talked about everything under the sun and we fought like brother and sister at the very top of our lungs. It was so wonderful to watch her get angry and it was wonderful to watch her laugh. We passed some great moments together I am very proud to say and we confronted some terrible things. She is gone now. We have our memories and her work. I think we must resolve not to fail her for she certainly did not fail us. (193).

A few years later Nina Simone wrote a song to honor Hansberry titled “Young, Gifted, and Black.” It was inspired by a speech titled “The Nation Needs Your Gifts” that Lorraine gave to encourage young black writers to tell the truth of their experiences and leverage their creativity in the work of justice. Her words are as resonant today in our age of #BlackLivesMatter as they were when she first spoke them. She said, “Though it be a thrilling and marvelous thing to be merely young and gifted in such times, it is doubly so to be young, gifted, and black….” She continues in words that are so powerful to hear at the beginning of Black History Month: “You are the product of a presently insurgent and historically vivacious and heroic culture, a culture of an indomitable will for freedom and aspiration to dignity” (197). Nina Simone said her hope for the song was to “make black children all over the world feel good about themselves forever” (Wikipedia).

Today, more than five decades after Lorraine Hansberry’s premature death, part of her legacy is that Raisin in the Sun remains “the most frequently produced work by a Black American playwright” (199). The title of the play is from Langston Hughes’ poem “Harlem,” which asks what happens when dreams are continually deferred. One answer the poem offers is that dreams can “dry up / like a raisin in the sun.” But both Hughes and Hansberry knew that another answer, as in the poem’s final line, is that the deferred dream can “explode” — as in the riots (or, better, “uprisings”) that were to come. Hughes’s poem—and Hansberry’s play—remind us that, “The battles Lorraine fought are still before us: exploitation of the poor, racism, neocolonialism, homophobia, and patriarchy. She models some of what we must do to confront them: use frank speech, beauty, imagination, and courage. And be with the people” (200).

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles