I started making plans for this post almost a year ago, when I saw that Beacon Press had published a book titled With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism. Dorothy is how she prefers to be called, and her story felt like both an appropriate topic for Women’s History Month, and a bridge linking back to Black History Month.

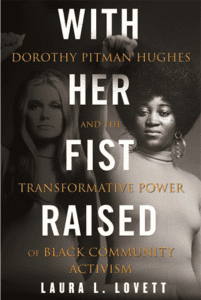

The book cover caught my eye first, because it features the famous photo of Gloria Steinem (who is white) and Dorothy Pitman Hughes (who is Black) standing side by side in solidarity, two icons of the women’s movement, both with their fists raised in the Black power salute. That cover photo has been altered to put Steinem slightly in the shadow and Dorothy Pitman Hughes in the spotlight.

The book cover caught my eye first, because it features the famous photo of Gloria Steinem (who is white) and Dorothy Pitman Hughes (who is Black) standing side by side in solidarity, two icons of the women’s movement, both with their fists raised in the Black power salute. That cover photo has been altered to put Steinem slightly in the shadow and Dorothy Pitman Hughes in the spotlight.

Some rebalancing along those lines might be needed. Speaking at least for myself, prior to reading this book, I knew a lot more about Gloria Steinem than I did about Dorothy Pitman Hughes. Perhaps that’s the case for some of you as well. (In contrast, if you learned a lot growing up about Dorothy Pitman Hughes, that’s great, and I would be interested in hearing more about that from you.)

Let me give you a recent example of how even powerful Black women have historically been pushed out of the light and into the shadows: did any of you watch the Hulu mini-series a few years ago called Mrs. America, about the struggle to pass the Equal Rights Amendment? It was a great tv series in a lot of ways, including its fascinating scenes with Gloria Steinem; but Dorothy Pitman Hughes wasn’t in it at all, even though she was a co-founder of Ms. magazine. So, I am grateful for this first full-length biography of this “trailblazing Black feminist activist whose work made children, race, and welfare rights central to the women’s movement” (Beacon Press).

And although I’ve been planning for almost a year to write on this topic, it has come to feel even more relevant following the week of confirmation hearings that may result in Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson becoming the first Black woman to sit on the Supreme Court. Hearing about Judge Jacksons’s confirmation hearings—even while reading about the life of pathbreaking community organizer Dorothy Pitman Hughes—has prompted me to reflect quite a bit about the long arc of social justice, because although there remains a long road ahead of us to build the world we dream about, we are nevertheless raised up on the shoulders of the giants who have come before us, whose ripple effects continue to play out in profound ways from generation to generation.

But before we focus on Dorothy Pitman Hughes, I want to invite us to take a step back to consider a longer view, a view of the astonishing work of so many other political activists in creating social change, work in which she played a significant part.

The relative lack of cultural recognition currently received by Dorothy Pitman Hughes renews my appreciation for the importance of today’s nomination of Judge Jackson to be the first Black woman Supreme Court Justice, and also of the recent election of Kamala Harris as the first Black and first Asian American Vice President. I bring up the names of these two women in particular because, when they were each nominated for their respective positions, they both did something similar that caught my attention and challenged my thinking; when they credited the Black women who helped pave the road they are now walking—and in so doing, they challenged me (and potentially many of us) to learn to tell our society’s history in broader, more inclusive ways.

When Judge Jackson was nominated in February, she noted that she shares a birthday with the Honorable Constance Baker Motley (1921-2005), the first Black woman to be appointed as a federal judge. Jackson and Motley were born 49 years apart (White House). What Jackson is poised to accomplish, she attributes in part to the tremendous legacy of the pathbreaking Black women who came before her. And here’s the thing: I want to be honest that there were various points in time when I could have told you who Constance Baker Motley was, and other points when I would have to confess that that name sounded familiar, but I’m not sure exactly what she was most known for.

But I am grateful to Ketanji Brown Jackson for lifting up Motley’s life and legacy—and thus challenging us to tell our nation’s collective story better. It is beautiful to notice all the ways that Constance Baker Motley being the first Black woman to be appointed a federal judge made it possible for another Black woman born two generations later to become the first Black woman Supreme Court Justice. The arc of history bends with a frustrating slowness sometimes, but there is also tremendous hope when we can look back and see that it has bent toward justice.

Justice Jackson’s invocation of Constance Baker Motley resonated with me for one other reason. It reminded me of Kamala Harris’s acceptance speech when she was nominated the first woman, first Black, and first Asian American Vice President of the United States. One part of her acceptance speech that stood out most for me is when Harris gave a shoutout to Constance Baker Motley, as well as to six other Black women: “Mary Church Terrell, Mary McCleod Bethune, Fannie Lou Hamer, Diane Nash, and Shirley Chisholm.” Harris did not detail their accomplishments. She simply said, “We’re not often taught their stories. But as Americans, we all stand on their shoulders” (New York Times). She was right.

Here, I’ll again confess that I cannot tell you off the top of my head who all of those women were. Some I recognized, but sadly realized I was hazy on the details. Shirley Chisholm (1924 – 2005) I know. She was an incredible force in politics. In 1968 she became the first Black woman elected to the United States Congress, running under the slogan “Unbought and unbossed.” She was also the first Black candidate for a major-party nomination for President of the United States. Likewise, I know a fair amount about Fannie Lou Hamer (1917 – 1977) and her activism for voting and women’s rights; indeed, I almost wrote a post about her this year, but it had to be changed to next year due to rescheduling.

Some of those other names I had to look up. As Vice President Harris said, “We’re not often taught their stories. But as Americans, we all stand on their shoulders” Representation matters. And centering a greater diversity of people here in this sanctuary—and in the state and nation too—increases our collective awareness of telling our nation’s story in wider, more inclusive ways.

The arc of history sometimes bends surprisingly fast, but usually it bends infuriatingly slowly! It can even reverse itself for a time. But I want to invite us to notice that the arc of history was bending all during Shirley Chisholm’s quixotic campaign for President in 1972, a run which helped pave the way for Kamala Harris’s election as Vice President two generations later.

Over time, this slow shifting of our societal tectonic plates creates propulsive possibilities. Some of you may remember Jay-Z saying it this way: “Rosa Parks sat so Martin Luther King could walk. Martin Luther King walked so Obama could run. Obama’s running so we all can fly” (Guardian).

Now admittedly, Jay-Z said that in 2008, and we all know that eight years of the first Black President did not solve racism in America. But as with the examples of the slow arc of history and progress that we’ve been considering, it may take more generations to fully appreciate their implications. That means it may be another thirty or forty years to pass before we all really grasp the most profound ripple effects from our first Black President of the United States.

So, this narrative has been a little bit of the long way around; but it felt important, after this week of Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearings, to trace some of these echoes of influence.

Now let me be sure to share with you some highlights about the rich life of Dorothy Pitman Hughes—how she and Gloria Steinem came to be standing together on that stage, and about all that happened before and since, and all that continues to happen. After all, unlike many of the historical leaders we explore in this blog, Dorothy Pitman Hughes is a living historical figure. Today, she’s in her mid-80s!

Dorothy was born in 1938 in a small town in Georgia, south of Atlanta (7). Part of what opened her imagination about what might be possible beyond the borders of that small rural community is that her father was a truck driver for the lumber industry. His journeys to faraway states and cities seeded her with a curiosity to grow up and explore the world for herself (18).

And she started those adventures early. Remarkably, at age 11, she started walking—two hours round trip—to attend the closest regional meeting of the NAACP (19). And also interestingly, one of her biggest takeaways from that formative experience was the prejudice she experienced at NAACP meetings for coming from a poor, working-class community. She learned early on of the need to work, not only to dismantle racism, but also to break down class barriers (19).

Dorothy was also a talented singer, so not long after graduating from high school, she took an unusual leap. In 1958, she traveled to New York and cobbled together jobs as a live-in domestic worker during the day and a nightclub singer in the evenings (23-25).

In 1964, she married Bill Pitman, who was white and Irish. She used to say that, “Six hundred years of colonial oppression of the Irish by the English meant he might be able to understand hundreds of years of African American oppression by whites.” And in ways that presaged her later work with Gloria Steinem, she tended to emphasize similarities between herself and Bill as ultimately greater than their differences (36-37). More poignantly, she used to say that she had “no hesitancy about using white men to accomplish the Black revolution” (38). Fair enough.

Part of what is most inspirational and practical about Dorothy’s approach to social justice is that she is a great model of focusing on what is specifically needed, both in your own life and in the lives of those around you. In the mid-1960s, when she looked around at her life and the lives of her neighbors, she noticed one glaring need that stood out above the rest: quality childcare. So she started by going up and down the street, knocking on all the doors of people whom she knew had children, and listening to these parents about what their needs were (43).

The relationships built through those conversations birthed the West 80th Street Day Care Center:

More than a thoughtfully run childcare center, it provided job training for volunteer mothers who got off welfare and enrolled in college courses in early childhood education and summer jobs for local teens, among other initiatives. Dorothy recruited teens to survey local food costs, only to discover that prices went up just before welfare checks were issued. A campaign run out of the center brought that practice to an end. (46-47)

And when Gloria Steinem was assigned to write an article on the center, that’s how she and Dorothy met (46).

Significantly, Dorothy’s feminism was not inspired by Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex or Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique—not that there’s anything wrong with that. Those books were more where Gloria Steinem was coming from. But Dorothy’s feminism grew more out of a lived sense of many men ignoring the needs of women for “safety, food, shelter, and childcare” (61). And that’s part of what made Gloria and Dorothy such a dynamic and influential pair as they toured the country from 1969 through 1973, speaking frequently in public together: they brought different, but complementary, worldviews and experiences to the table (63). (If any of you saw them in person I would be interested to know.)

Dorothy was also extremely helpful to Gloria Steinem early on because Gloria did not initially like public speaking, whereas Dorothy was an old hand at taking the stage, given her years as a nightclub singer (63).

When Dorothy was occasionally questioned about why she as a Black woman was spending so much time helping a movement that primarily centered the needs of white women, she would say that, “[s]he wanted to be part of a movement to empower women” (66). On the one hand, she recognized that the relationship she had built with Gloria “was not representative or easily reproduced” (73). On the other hand, she treasured the fact that her friendship with Gloria also represented a point of real hope from which it was truly possible to build bridges across racial divides (64).

Relatedly, I love the story about how Dorothy’s family belonged to a theologically conservative Baptist church in rural Georgia that was opposed to women holding all but social leadership positions. Despite her commitment to women’s liberation, she would always visit her childhood church whenever she was in town; in the early 1970s, she helped racially integrate that church by bringing the very first white person to ever visit the church: Gloria Steinem. That must have been quite the Sunday. Dorothy said the congregation “sort of thought I was crazy…[T]hey called me Black Panther” (8).

There’s so much more to Dorothy’s story, including the fact that in recent years, Gloria Steinem helped Dorothy’s family save their land against a predatory buyout attempt by a corporation (115). One of the ways they did that in 2017 was with a fundraiser built around re-staging that famous photograph of the two women side-by-side with their fists raised—except this time Gloria was eighty-two and Dorothy seventy-nine (118). You can easily find that image if you google it.

For now, in conclusion, let me link us back briefly to last week’s column on “Building a New Mythology.” Some of you may remember that we spent some time reflecting on Toni Morrison’s admonition to “Dream a little before you think.” Don’t just think within received categories, systems, and institutions as they currently exist. “Dream a little before you think” — just as Dorothy did when dreaming up and creating her Community Childcare Center, just as all those other pathbreaking, trailblazing, visionary “firsts” did. They all had to dream a little, not just about what was, but about what might be. Then they turned their dreams into deeds.

I want to conclude in that spirit with just one more example that can help us dream a little about what might be. Do I have any Trekkies out there? Specifically, is anyone watching Star Trek: Discovery? I won’t get too spoilery, but the show is notable for a number of reasons, including casting a Black woman as the ship’s captain. But the real reason this show is coming to mind now is that a recent episode had quite the surprise cameo, casting Stacey Abrams as the United Earth President—a Black woman (and distinguished contemporary politician) as President, not just of the United States, but of the whole planet (Hollywood Reporter). That alone is a beautiful vision in line with the Internationalism of our UU 6th Principle of world community that our youth group spoke so powerfully about a few weeks ago.

Inclusive visions of the future can inspire us to dream a little before we think. We are called, after all, not only to better learn the history that has come before, but also to be part of making the history that future generations will inherit. What work might we do, both individually and together, the ripple effects of which might not come to full fruition for two generations or more? In a few weeks, on Earth Day, we’ll explore this question further through a frame of “how to become a better ancestor.”

In 1966, when Constance Baker Motley became the first Black federal judge, you’d really have to squint to see that 56 years later, that earlier inflection point would help create a world in which Kentanji Brown Jackson is likely to become the first Black woman to sit on the Supreme Court. Similarly, in 1972, when Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman to run for President, you’d really have to squint to predict that fifty years later, Chisholm’s candidacy would have played such a significant part in creating a world in which Kamala Harris could become the first Black woman ever elected Vice President. (Now, to be honest, I suspect that if Chisolm were alive today, she wouldn’t be satisfied with the role of VP. I suspect she would be saying, “Wake me up when Stacey Abrams is President!”

We live in a hard and treacherous time, but we can also do what Dorothy Pitman Hughes did: we can look around and ask, what do I need? What do my neighbors need?

And then we can work together to build coalitions across our differences to create a better world. For even though we cannot know in advance what ripple effect might be initiated as a result of our work a generation or two hence, we owe it to ourselves and to future generations to try our best to make it so.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles