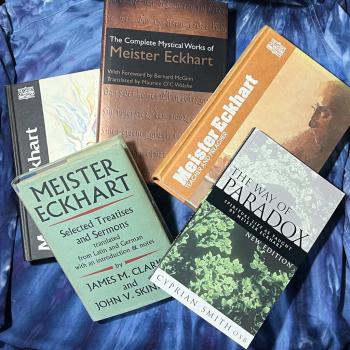

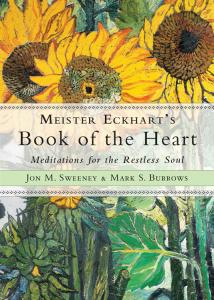

Today’s post is by a guest contributor: Mark S. Burrows, who along with Jon M. Sweeney, is co-author of Meister Eckhart’s Book of the Heart: Meditations for a Restless Soul.

In one of his characteristically witty remarks, G. K. Chesterton reminded us that each generation is converted by the saint who contradicts it the most. This might be a salutary reminder in times like ours, when many among us seem driven to follow some crowd or other, and the ensuring cultural friction generates far more heat than light. What Chesterton meant was that each age needs a counterforce to keep its balance and avoid falling into confining postures of thought and belief.

Now this might seem a strange way to introduce Meister Eckhart, whose thought—or selected assertions, wrestled out of context—was condemned by the Church as heretical. In point of fact, Eckhart might suggest—were he here to do so—that contradiction belongs to the essence of faith, at least for those, like him, who were intent on summoning us to follow the mystics’ “wayless way.”

What is it about his thought that might provide light and inspiration in our times?

The startling appeal of his wisdom has always been strongest among those who seek to live contemplatively in the world, and who thus know that a salutary disengaging is important in the spiritual journey. He knew that following the prevailing tides of cultural opinion or ecclesiastical practice was generally a bad idea. Why? Because we become enervated by indifference or its inverse, misguided enthusiasm. We need to keep a critical and creative distance from both poles, emptying ourselves of what we expect—or are expected—to believe or know, in order to approach what is true more faithfully.

His favored way of putting this is gathered in a single word he coined: “Gelassenheit,” which we might render, quite literally, as a “letting-be-ness” or “releasement.” This composure, or calmness of heart, offers to open us to what is in our world, and in our lives. But this is only part of the challenge. The other part is finding the inner unity that is our soul, beyond the clutter of distractions that preoccupy us so much of the time. Beyond this, as Eckhart knew, was a proper attunement of the heart.

How are we to do this? Eckhart once put it this way:

If we were to pour pure water into a vessel both empty and clean and let the water become utterly still, and then leaned over it to see our face, we would see a perfect reflection gazing back at us. This is because the water itself is pure and still. It’s like this, too, with each of us when we’ve found inner freedom and unity: if we open our hearts to God in peace and solitude, we’ll be open to God in strife and turmoil.

Or, as he elsewhere put it,

Examine yourself, and wherever you find yourself, take leave of yourself. This is the best way of all.

Or, again:

You must know that there is no one in this life who has let go of himself so much that he did not find that he could let go even more.

In an age like ours, bent on self-discovery or self-actualization, such a notion might seem absurd. And, indeed, it is surely nonsensical. But that is one of the gifts mystical vision like Eckhart’s can bring: a nonsense that might well save us from the often painful, dead-end journey into the false self.

For Eckhart, the truth is to be found in the unexpected places of the heart—in our world, in the lives of others around us, and in our own lives. This is what empowered him to say that we must always seek the “God beyond God,” the divine One who refuses to play hostage to our finite perceptions.

Eckhart knew that religion is not always the problem, though rarely is it a solution to our yearning for what is true, good, and beautiful. Rather, we must learn again and again to let go of the settled conventions of religion in order to give ourselves to the longing within us, a yearning that might bring us to our true self. This might even seem to be a letting go of ourselves, as indeed it must be in order to discover something larger and truer than our constructions of self, other, and God.

In one of the poems included in Meister Eckhart’s Book of the Heart, entitled “To Let Go of All,” we put it this way:

The cup must be empty

to find its true meaningbeyond every kind of

usefulness, so emptythat it would not know

why it is a cup or towhat end, poor and use-

less and without a singlepurpose it could know,

which is what I, too,must learn to be if I

would be free, strivingto let go of all I hope

might fill me so that allthat is finally left is God.

The same intent finds an even more startling form, and radical expression, in this one, whose title is the first line:

What then should I do

but dare to let go of my wish to be

something or someone, and let Yoube nothing and no one, and so let

my being-me sink into Yourbeing-You and so my me and

Your You become one single One.

This is Eckhart’s way. It will call us to risk what we know so that we might open ourselves, in our emptiness, to who we truly are. Only in this “wayless way,” as he sometimes put it, might we come to glimpse something of the One Truth—and, finally, give ourselves more truly to the One who is. This is the way of the restless heart that calls us, again and again, to let go for love’s sake.