Today’s guest post is by the Reverend Stuart Higginbotham, an Episcopal priest and contemplative teacher. He is the co-editor of a newly released anthology of essays by young contemplatives, Contemplation and Community: A Gathering of Fresh Voices for a Living Tradition. In this post, which originally appeared on Fr. Stuart’s blog, he tells how being the target of protests by Westboro Baptist Church during last February’s Super Bowl helped him and his parish to grow in their own commitment to contemplative spirituality.

What My Encounter with Westboro Taught Me About Contemplation and Parish Leadership

by Stuart Higginbotham

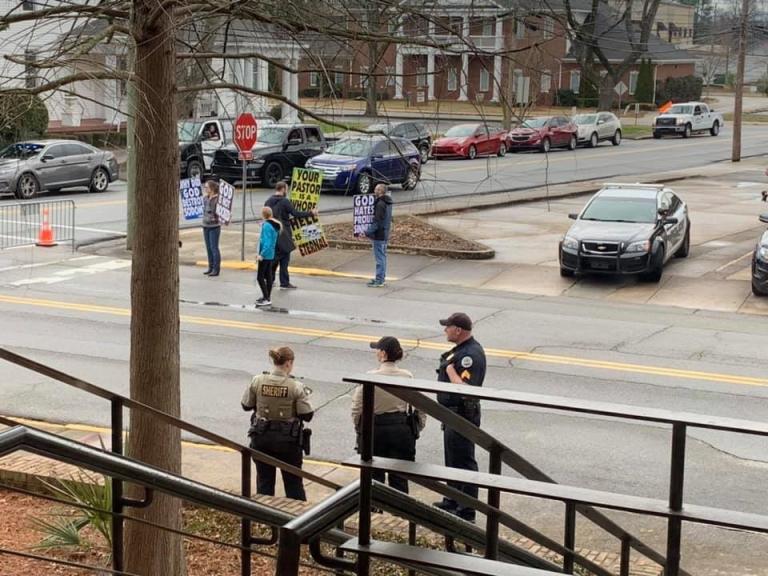

We still don’t know why Westboro came to Gainesville, Georgia. Some have suggested they found an ample block of hotel rooms within a relatively short distance from the stadium where they would protest the Super Bowl. The problem with this is, if you draw a circle forty miles in diameter from the stadium, there are more than enough small towns with hotel rooms.

Some have suggested that the man in town who wrote thinly-veiled threatening letters laden with isolated Bible verses and came at me in a liturgy last year may have actually reached out to them. I can tell you the energy felt the same with both him and them, but who knows if they coordinated. If I think about this for too long, it makes me uncomfortable.

Westboro themselves told a local paper that they targeted Grace because The Episcopal Church is “the most evil institution in the history of the United States.” I can think of many more who out-perform us in that category.

Others have suggested that it was, in reality, purely random. They simply had the goal of getting to the Super Bowl, wanted to arrive a bit early and spend time protesting a group of churches relatively close, and wanted the attention which they knew they would gain once their lawyers contacted the local police department. Once that notification was made—and various counter-protest groups filed for their permit to protest—our phenomenal law enforcement had no choice but to follow a protocol that ended up closing streets, establishing perimeters, surrounding the nave with armed guards, utilizing a mobile surveillance unit to follow the schedule of the protesters, and employing a helicopter to monitor the entire complex situation spread over six locations in a small town that is not accustomed to Sunday mornings being quite so exiting. I will be forever grateful for the care and dedication of both our city and county officers.

So, I don’t know why they came to Gainesville. I only know that it happened and I found myself in the position of suddenly needing to embody so many of the lessons I had offered on the vital role of a contemplative posture in a parish church. It is all well and good to invite a congregation to consider what it looks like to respond from the spiritual heart, to remain grounded, to be aware of the movement of the Spirit, and to embody compassion in the midst of struggle. While I have had the chance to write on the Elements of a Contemplative Reformation and the potential for a renewal of awareness, practice, silence, and compassion within a traditional congregation, I never imagined I would need to practice this with hovering helicopters, armed officers, signs reading “Your Pastor is a Whore,” one particular group of counter protesters armed with cowbells, and anxious—yet fiercely compassionate—parishioners.

The lectionary readings for that Sunday were assigned decades ago in the three-year cycle that we use. In the midst of this progressive breakfast of weirdness, we found ourselves gathered around the following images from Jeremiah 1:4-10:

The word of the Lord came to me saying,

“Before I formed you in the womb I knew you,

and before you were born I consecrated you;

I appointed you a prophet to the nations.”

Then I said, “Ah, Lord God! Truly I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy.” But the Lord said to me,

“Do not say, ‘I am only a boy’;

for you shall go to all to whom I send you,

and you shall speak whatever I command you,

Do not be afraid of them,

for I am with you to deliver you, says the Lord.”

Next came the reading from I Corinthians 13:

If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love.

Finally, the Gospel reading from Luke 4 was the story of Jesus challenging the constrictive view of those gathered in the synagogue. When he reminded them of Elijah’s encounter with the widow at Zarephath and Elisha’s healing of Naaman the Syrian—challenging the assumption that Israel alone received God’s grace—they became so enraged that they tried to throw him off the cliff. Jesus’s response is convicting: But he passed through the midst of them and went on his way.

One reporter who had initially come at the beginning of the service to take photos but ended up staying for the entire liturgy could not believe I did not choose the readings specifically for the protests outside. “If we don’t wonder about the Spirit’s guiding presence when we see images of God’s affirming knowledge, cautionary lessons of noisy gongs and clanging cymbals, and Jesus’ calm grounded presence laid alongside experiences like this,” I told the reporter, “perhaps we’re just being stubborn.”

Given that we had a two-week notice to prepare for their arrival, we also had two weeks to worry and imagine all sorts of frightening scenarios. As I met with some of my team in the hallway—where most of our good, grounded work seems to take place—I wondered with them what it might be like to respond out of a contemplative posture both symbolically and compassionately.

As an Episcopal Church, we keep symbols at our fingertips, and we often take them for granted. As we seek to remain aware of the rich fullness of the Christian tradition of which we are a part, we often become so accustomed to conspicuously-placed baptismal fonts, altar rails, and candles that we give less and less thought to their capacity to nurture a transformative experience. Why do we need the font near the front door? What is the significance of kneeling alongside each other while receiving Holy Communion? Why does it stir our hearts to see a recent widow light a candle before the service?

While speaking with the staff that day, I heard our tower bells toll the hour and realized what an incredible opportunity we had to offer a message of love that truly resonated with the wider community. We decided that we would peal the bells for the duration of the protests, on one hand to drown out the messages of hate and anger that were directed at us, but also—and more importantly I think—to offer a symbol of compassion that would echo into the surrounding community. “Ring the bells that still can ring,” the prophet Leonard Cohen reminds us.

When word got out in the parish that the protest was coming, some immediately began plans to make posters and counter protest themselves. My heart told me this wouldn’t be helpful, and it felt like a reactive response. Howard Thurman whispered in my ear: “How good it is to center down…” I was curious about the impulse we have to counter loud words with louder words, even if they are words like “God loves you.” How can we speak and respond out of a deep, yearning silence that seeks an awareness of God’s presence? Something in me told me to pay attention to this impulse toward loudness and to wonder what a response from a contemplative posture might look like, a response that sought to get under the loud words, noisy gongs, and clanging cymbals. What could we do with the energy that we felt, an energy that needed a creative focus that would harness—even transmute it—from anxiety, fear, and tension into compassion? As rector of the parish, what was my particular role in this?

After talking with a few folks, I wondered if we might actually focus ourselves toward a time of grounded prayer and worship as well as a community compassion drive for the local food pantry and Humane Society. Would that nurture our own embodiment of compassion in the midst of tension, yelling, vile reminders of our “whoredom,” and cowbells?

Parish leaders, the children and youth of the parish, and the staff all focused their hearts and helped co-create a day that was one of the most significant I have ever experienced. We sang our hearts out, we held a time of silence, we reaffirmed our baptismal covenant and pledge to “respect the dignity of every human being,” and we collected an enormous amount of food and pet supplies. As I walked around between the services, my heart smiled seeing two sheet cakes given by our friends at St. Catherine’s in Marietta (they have a thing for sheet cakes). Colleagues from the diocese came to worship with the community at Grace. Holy Trinity Parish’s clergy and vestry just happened to be present after finishing their annual retreat. People who had not been to church in years came to take their place in the circle. The love was palpable, and when I made it to my seat during the procession, I looked out and felt a parish that was truly living from a contemplative posture with an awareness of God’s indwelling presence, a recognition of the importance of centeredness, and the call to share Christ’s compassion with the entire world. The heartful singing our choir led could have drowned out a helicopter even if it landed on the front porch at that point.

Here is what Westboro continues to teach me: spiritual leadership grounded in a contemplative posture is possible and crucially important in this day and time. In the two weeks leading to that Sunday—and especially while in the midst of it—I kept mentors and teachers close to me. I paid attention to glimpses of grace that floated into my field of vision, that bubbled up to rest in my heart. My own struggling daily practice became essential, and I found myself wrapping up in my prayer blanket to spend time in a deep, yearning silence that anchored me in the swirl of details. I paid attention to where I felt constriction and tension in my body. I noticed when my breathing became shallow, because if I, as rector, wasn’t able to breathe, I wondered if that affected my colleagues and the parish as a whole.

Several saints and sages are important to me when it comes to a contemplative posture and leadership. The words of Jean-Pierre de Caussade are important as he invites us to consider what it means to belong wholly to God. Recognizing our tendency to assert ourselves, he affirms that we have but one single duty: “It is to keep one’s gaze fixed on the master one has chosen and to be constantly listening so as to understand and hear and immediately obey his will.”[1] I was vividly aware of the importance of knowing where I was focusing—on whom I was focusing.

I also thought of conversations with Tilden Edwards and the challenge of truly recognizing the presence and work of the Holy Spirit. It is one thing to give lip service to the Spirit’s guidance; it is another to open your heart to acknowledging the movement of the Spirit of Christ and the invitation we have to trust in that guidance. I thought of the way Tilden reminds us of the “capacity” within us for a “spaciousness” between and underneath the words we become so easily preoccupied with. In that creative space we just may encounter the Living Christ who pours His life into our heart as He invites us to share in His.[2]

As well, I thought of Beverly Lanzetta’s work and her wonderful challenge to recognize the social implications of truly living out of a contemplative posture. Doing our own inner work is not a selfish endeavor; rather, it nurtures the way we can respond when we face the inevitable tensions of our lives—whether they be a Westboro protest or the Thanksgiving dinner with your family that you dread each year. Drawing on the life of Teresa of Avila, Lanzetta offer us a remarkable image to ponder when it comes to the call of spiritual leadership:

Learning to see the world through the lens of the mystical and becoming fluent in its language were essential to [Teresa’s] maturity and empowerment. No less true for our times, we require education in the divine pedagogy and benefit from access to the alphabet and vocabulary of the spirit.[3]

Looking back, I can say that whatever positive response I was able to give in that moment—and all moments of stress or tension in parish ministry—I was only able to give it because of the centeredness offered through my struggling contemplative practice. I recognized that my own visibility as the rector of the community meant that I was responsible all the more for my own prayer life. By seeking to rest more and more in an awareness of God’s presence in my life, I hope I was able to remain faithfully present in the life of my parish. I think that is a dynamic worth pondering.

About the Author: The Rev. Dr. Stuart Higginbotham serves as the rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Gainesville, Georgia. He is a priest, writer, retreat leader, husband, and father. He has a deep desire for a contemplation reformation, an exploration of how the Christian contemplative tradition can shape, nurture, and challenge the institutional church.

This post originally appeared on Stuart’s blog, Thoughts on a Contemplative Reformation, and is reprinted by permission. Visit the blog here.

[1] Jean-Pierre de Caussade, The Sacrament of the Present Moment (Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Company, 1981), 9.

[2] Explore Tilden’s book Embracing the Call to Spiritual Depth for a wonderful series of reflections and exercises for cultivating a contemplative posture.

[3] Beverly Lanzetta, Radical Wisdom: A Feminist Mystical Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 27.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.