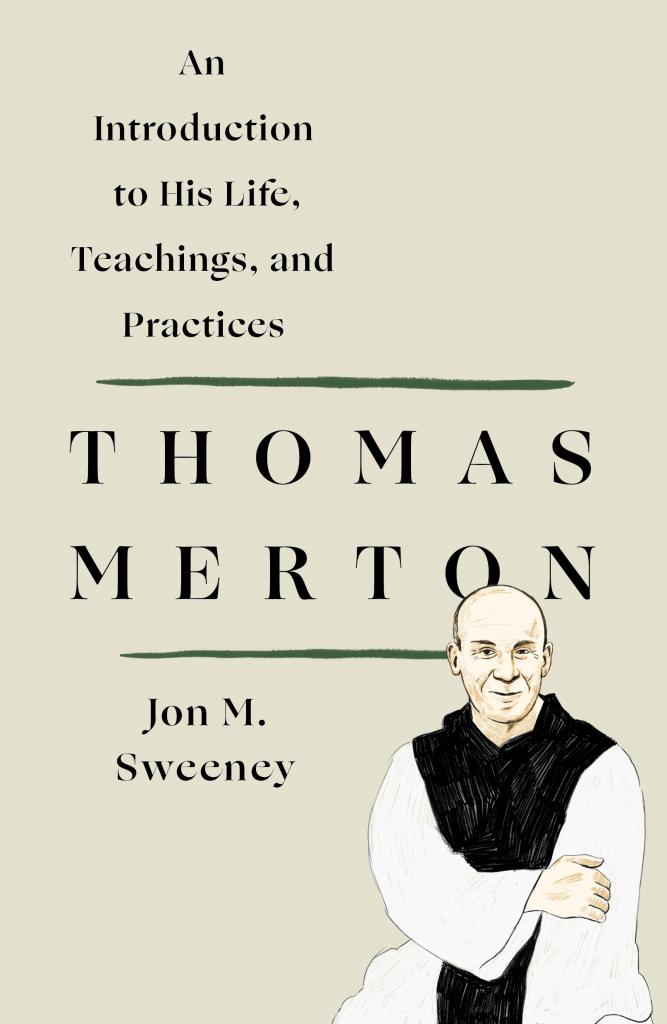

N.B. Today’s guest post is by Jon M. Sweeney. Jon is the author of numerous books, including The Pope Who Quit, Beauty Awakening Belief: How the Medieval Worldview Inspires Faith Today, Phyllis Tickle: A Life and The Pope’s Cat among many others. He has edited works by Thomas Merton, Meister Eckhart, and others (Jon also edited my book on C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Mouse and the Dawn Treader). His newest book, released today, is Thomas Merton: An Introduction to His Life, Teachings and Practices. Jon has contributed to this blog before: click here to see some of his previous posts. Today, he tells us why he wrote about Thomas Merton.

WHAT BROUGHT ME HERE: WHY I WROTE A BOOK ABOUT THOMAS MERTON

I was only a year old when Merton died. But when I was seventeen and contemplating having to register with selective service as eligible for the draft, I had a feeling that I shouldn’t be willing to kill others, even in a war. I didn’t find people who were friendly to objecting to military service in my church, but someone pointed me to a Mennonite nonprofit nearby, and I met with the director there. It was he who first put a Thomas Merton book in my hands: a collection of Merton’s writings on peace. Then, when I was nineteen, after having devoured The Seven Storey Mountain’s five hundred or so pages in three days of excited reading, I made the first of several visits to Merton’s monastery in Kentucky, pondering a monastic life. Should I? Eventually, I decided no. Instead, I would try to be what is sometimes called a “monk in the world.” I became a disciple of the teachings of those who emphasized the contemplative aspect of the spiritual life.

Today, there are far fewer monks left at the Abbey of Gethsemani than there were when Merton was alive. Hundreds of monks lived there at one time, some sixty or seventy years ago. Today, they are only a few dozen. Organized religious life is on the wane everywhere you look, and monastery populations are no exception. The population of every monastic community has been aging every year for decades. Some monasteries have closed. Others survive only because they have become places of retreat, as people like you and me visit for a weekend or two a year. Also, many monasteries have a large numbers of oblates, or associates—laypeople who commit to living with monastic rhythms and spiritual practices, and financially support the monastery. I suspect that Merton could see that this would one day be the case.

Those of us who visit monasteries on retreat, and who pursue the spiritual practices of someone like Thomas Merton, are indeed among the keepers of the monastic way. We don’t—we can’t—do it like he did. But in many ways, we can be monks, and in many ways, Merton showed us how. I wrote my book in the hope that it might help you find your way with him, his writings, and his spiritual practices.

HE CONFUSES A LOT OF PEOPLE

“We are all secrets,” Merton wrote one day in his private journal. In other words, there are limits to how much we can understand ourselves, let alone each other. Particularly, we can’t presume to understand someone else’s religious or spiritual life. What is “on the surface” tells only a fraction of their story.

Another twentieth-century favorite of mine is Edith Stein, the Jewish philosopher who converted to Roman Catholicism, became a Carmelite nun, and then died in a Nazi concentration camp. The Nazis didn’t care if a Jew had converted to another religion. After her tragic death, Stein became a saint in the estimation of the Catholic Church, whereas I’m sure Merton never will receive such an honor. (More on that in my book.) She’s officially known in the church as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. Still, her niece once asked her about her conversion to Catholicism from Judaism, and Edith responded with a Latin phrase: “Secretum meum mihi.” “My secret is mine.”

I think you’ll find that this is very true of Merton, as well. Our secrets are our own, particularly when it comes to who we are in our relationship with a God who, when communicating with us, if at all, often does so in a whisper.

This is one way of suggesting that we’ll never fully understand our subject. It is also a way of saying that Merton’s willingness to consistently and consciously be on pilgrimage, to talk with us while he’s searching for what he’s looking for, and to acknowledge that the search never stops in this life—that the answers are not often clear or simple—makes him an evergreen teacher of spiritual wisdom.

Popularly understood, he was a contemplative monk who introduced the possibility of a deep religious and spiritual life—something one might imagine exists only in a monastery—as available to anyone, whether they lived in a cloister or a city, were Christian or some other religious tradition, and whether or not they felt certain in their beliefs. His own life was full of contradictions, as we will soon see, and it is these very contradictions that also make him appealing to us still. He seems to have found a real and deep personal connection to the living God, and yet some of his actions reveal how very human he remained. Yet that core understanding—that a monastic sort of life might be available to you wherever you live—remains compelling.

ONE MORE THING

Not long ago at the Abbey of Gethsemani, I spent an afternoon with one of the monks and a friend at Merton’s old hermitage in the woods. Although there is a right way to see this special place—by permission, without trespassing—it also isn’t uncommon for people to make their way to the hermitage in their own way, and the monks are generally gracious and forgiving about it. In fact, the trespassing has been happening since Merton’s own lifetime; he spent a fair amount of time ducking people in the woods who were trying to find “that famous monk.”

Merton liked to walk in the predawn hours as the mist was rising, observing wrens, cardinals, woodpeckers, and the occasional mockingbird along the way. On this particular morning not long ago, as my two companions and I were walking from the hermitage back to the abbey, I spied a folded single sheet of paper soaking on the grass in the morning dew. I bent down and picked it up.

Someone had printed out a Merton poem and carried it with them, probably to read it while sitting on the hermitage porch the night before. It had fallen out of the pocket, quite recently, of someone who had walked back down the same hill we were walking down. “His God lives in his emptiness like an affliction,” is one of the lines from the poem on that paper soaking in the dew. The poem is titled “When in the Soul of the Serene Disciple.” It was that emptiness, but also the knowing that God was there in it, that moved Merton throughout his life.

I tucked the poem in my pocket as we all walked down the hill in the woods, then crossed the road, toward where the gate used to stand that Merton was so happy had once enclosed him inside, about eighty years before.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.