The fortuneteller uses language. The diviner uses language. ‘Yeah, but my language is divinely inspired, while yours is just a representation of your knowledge,’ the modern diviner says to the fortuneteller, who will raise her brows and say: ‘Sure, if you say so. I’ll just have to believe you. After all, I’m in the business of believing.’

The fortuneteller uses cards, stones, stars, and bones. The diviner uses cards, stones, stars, and bones. ‘Unlike you, who sits there and decodes everything, cold reading too from body language to self-imposed delusions, I’m communicating a divine message with these,’ the diviner will say, while giving the fortuneteller the evil eye.

The diviner: ‘I keep telling people that they can change their future.’

The fortuneteller: ‘They can? In my experience, I say it and I hear it. People don’t like to be told what to do, so they go home and do their thing regardless of what I say. Which is exactly the reason why they come back to me. We’re in agreement about at least one thing: You don’t change anything. What changes is your conditions. Life happens as it happens, and you just want to hear a story about its unfolding. Sometimes this desire is not conscious, but it’s there nonetheless.’

The diviner: ‘No, no, no. It’s called mediumship. You channel the divine, creating a connection to the godhead.’

The fortuneteller: ‘Really? I thought you said you didn’t believe in linguistic conventions, as your message is inspired and transcends the symbolic and fictional glyphs of language.’

[On my part, I don’t think I want to call it anything. It is what it is. I look at the cards and tell you a story. If it answers your question, does it matter if my story is inspired or not?]

The diviner: ‘My task is to just be here, but not be here as ‘myself’, my ego and all the other ‘person’ masks that contaminates my message. I have to listen to the divine.’

The fortuneteller: ‘Good luck with what. I appreciate your Zen. Err, by the way, how long do you have to wait? When do you know when the divine hits you with a message that’s not the product of your own linguistic competence?’

The diviner: ‘It depends. It just comes to me and I just know things.’

The fortuneteller: ‘Ok, that certitude is impressive. I’m jealous.’

By the account of this exchange above, I’m a fortuneteller. Ok, a Zen fortuneteller. This means that I believe nothing, simply because I don’t take language as representative of reality. If I say, ‘there’s a world we see and a world we don’t see,’ what I do is make a statement, a speech act.

Speech acts are declarations that have a performative function. They can be both visual, verbal, or both. Shuffling my cards with my eyes closed, hand bejewelled by consecrated rings, is a ‘speech’ act that announces the invocation of some divine thing. The other I’m reading for seeing me like this is not into verifying what I’m doing and why. They are there to receive a revelation. So be it, amen. ‘Thank you for the powerful message.’

I don’t make claims to being plugged in to some invented divine power. My zen master would beat me very hard with a stick if I came up with such an idea. And I’m very afraid of my Zen master, though I love it when he beats the crap out of me.

The opinionated speech act

So here’s an opinion, since opinions are so popular:

Although there’s no difference between the functions that the fortuneteller and the diviner perform, we can see that culturally there’s a difference in signification at the level of the speech act:

Whether we deal with the statement: ‘I’m inspired by the divine’, or ‘I’m using my own god-given common sense to make sense of this shit’, what we’re dealing with are proclamations raised to the status of embodied action.

Embodied action follows categorization and hence a profession, not the truth or the thing itself. Embodied action follows language – the language that your mother taught you and that your culture taught you, and this includes the culture that taught you the idea that godheads speak to you via signs and omens and all you have to do is interpret.

The truth is that all we ever do is interpret. Interpretation is surviving. If you can’t interpret the valid linguistic codes for what culture deems is appropriate behavior, you’re fucked.

In fact, much of both divination and fortunetelling deals with the failure to interpret the world around us. People forget that even their pain is constructed by language, by the cognitive apparatus that enables us to label our emotions and sensorial feelings. It’s all concepts and beliefs.

If you want to be uncontaminated in your ‘divine’, ‘rational’, or so-called ‘ego-driven’ messages, what you do first and foremost is pay attention to the language you speak and the language that the other who wants to know things speaks. That’s the only honest task you can set for yourself. Anything else amounts to just claims that are bound to remain in the unverifiable realm.

Now, history has it that fortunetelling and divination alike have been working for ages because people like the unverifiable, as the unverifiable sustained by claims to connection eradicates the pain of self-scrutiny. It hurts to look at yourself and reflect on how and why you subject yourself to certain conditions. Many actually think that it’s better when others do the reflective thing, when they are given a recipe for this or that, when they are told what books to read, and what course of action to take.

People like it when the fortuneteller tells them: ‘If you go to work today, you’ll have an accident’. So they’ll have an incentive to stay at home and not feel guilty about it. People also like it when the diviner tells them: ‘Empower yourself. You create your own future. Your own will is the most powerful thing in the universe’. This bogus talk is seductive.

The payoff

To each their own. Buy it pays off to remember that whatever you say, you say it with words. Most people will take your words at face value, just as they might also take the words of the Bible at face value because there’s a presupposed divined authority that inspired the words in it.

Whichever way you put it, language is a tool of delusion. It doesn’t represent reality. It represents cultural rules and conventions, in other words, power games. Use it wisely, and think about what you’re saying and why.

To be even more confident, you might consult the way the dictionary of etymology defines the practice of divination. You’ll discover that not even this old repository of knowledge makes a black and white distinction between divination and fortunetelling:

Here’s a quote from the Online Etymology Dictionary:

divination (n.)

Late 14c., divinacioun, “act of foretelling by supernatural or magical means the future, or discovering what is hidden or obscure,” from Old French divination (13c.), from Latin divinationem (nominative divinatio) “the power of foreseeing, prediction,” noun of action from past-participle stem of divinare, literally “to be inspired by a god,” from divinus “of a god,” from divus “a god,” related to deus “god, deity” (from PIE root *dyeu- “to shine,” in derivatives “sky, heaven, god”). Related: Divinatory.

“Divination hath been anciently and fitly divided into artificial and natural; whereof artificial is when the mind maketh a prediction by argument, concluding upon signs and tokens: natural is when the mind hath a presention by an internal power, without the inducement of a sign.” [Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning, 1605]

When you’re done with the dictionary, you may recline in your chair and start reflecting on who decides what is natural and what is artificial. Isn’t that distinction also part of a linguistic convention? We can keep going…

I’d say, just read the damn cards, or signs, or dreams, or omens. See what there is to see, and leave it at that. Let your sharp vision and discernment do the job of counseling. Leave the labels of what you embody to the label makers.

Card clarity

Meanwhile, we can read some cards, we might have a conversation with the cards rather than about the cards – the topic of next week’s essay here on Patheos – and see what we get.

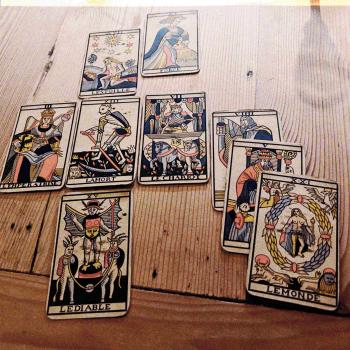

At the level of practice, since conceptually it’s hard to see just what the difference between fortunetelling and divination is, I asked this question of my old Tarot de Besancon, by Grimaud under the Arnoult signature (1898):

At the practical level, what does divination do and what does fortunetelling do?

I used the whole deck in one shuffle for a 3-card side by side:

For divination I got: Empress, Justice, Ace of Cups.

For fortunetelling I got: 4 Batons, 3 Cups, 6 Swords.

If I keep it simple I’d say that divination tells you what to do, while fortunetelling tells you what not to do. Divination will have you believe in higher orders, virtue and faith, things like ‘truth and beauty’.

Fortunetelling is for the ‘little people’ and their hardship. It will tell you this: ‘You believe in working with a community, you’re fucked.’ How about some self-reliance? It starts with discarding people and things alike.’

I could go on. But I’ll stop here. It’s a good thing I believe nothing. I just want a clear, not a cluttered head.

♠

You can experience some clear fortunetelling and divination for yourself, if you try Aradia Academy’s Fortuneteller’s Fair on Facebook on November 24. You can still get a ticket and praise yourself lucky. 20 bucks for the whole thing, which is 16 fortunetellers for 6 hours at your disposal for any and as many questions you might have.

Otherwise, you’re welcome to stay in the loop for future cartomantic courses and events.