In my work with the cards I strongly emphasize that we look at the function of what we see represented on the cards. This means that I’m more interested in what a character or a particular suit is doing, rather than what it is.

In the mainstream cartomantic set of ideas, everything IS. An archetype IS. The suit of swords IS.

When I read the cards, the only IS I’m interested in is the obvious, and I find that the obvious is rarely about a set of identity markers, but rather more about a set of actions: With a sword we cut, with a cup we drink, and so on.

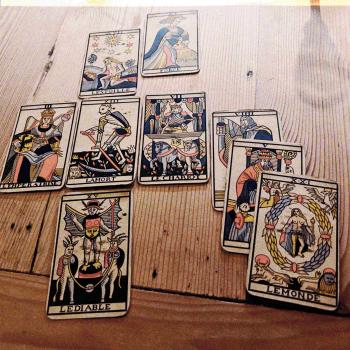

I like to read with art cards, because often the focus on what’s happening at the level of action is sharper than when I consider what I’m looking at as a matter of habitude, for instance the idea that the Empress is the embodiment of creativity, or Death the embodiment – or rather disembodiment as is actually the case here –of transformation. I mean, all cool with such ideas, until I get very tired of seeing the same image in the same way, which is the way of conceptual thinking, which is the way of not looking at the image at all, for, hey, the Emperor is the embodiment of control, they say, and it doesn’t matter how this power is represented, as long as I also say, ‘the Emperor means control.’

Let’s look at the implication of what I’m saying about paying attention to the idea of doing rather than being, or to function and action, rather nominal definitions.

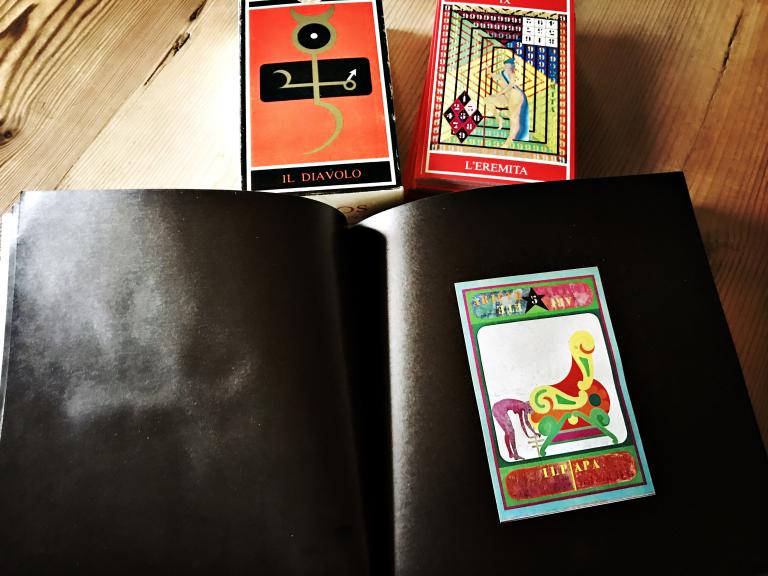

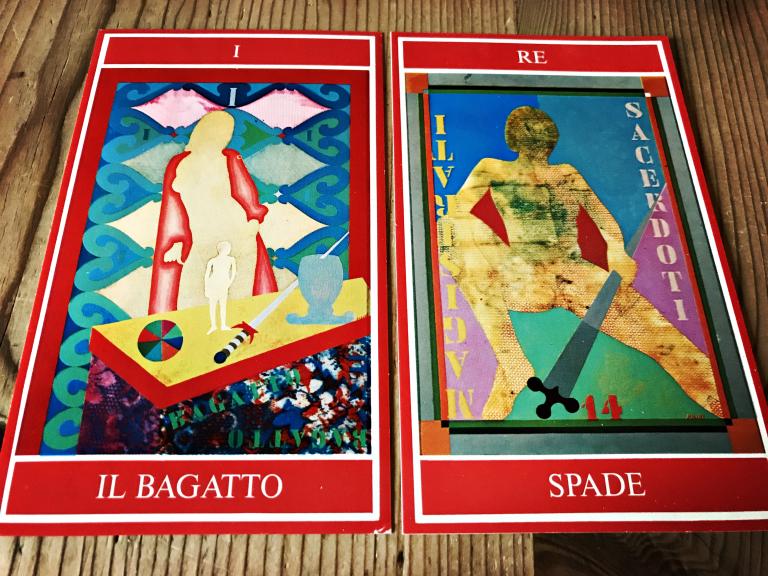

After a string of cards that spelt out the multiplication of enemies at work for the client I was reading for with one of my art tarots, namely Andrea Picini’s deck Il Diavolo, I pulled two more cards from the set, the Magician and the King of Spades.

The person asked immediately: ‘So, I have to be inventive about this enemy?’, clearly thinking about the Magician and the King of Spades in terms of being: one being clever, and the other one being mean.

‘No,’ I said, and then continued. ‘What you need is to focus on the sword on your table, sharpen it and use it like a master. Only a big focussed sword can get rid of 10 small ones.’

‘Ah, I see what you mean’, the person said, then lamenting about what ails her adversaries. ‘Everyone is so busy with speculating about my bank account. I don’t know how I can go against this.’

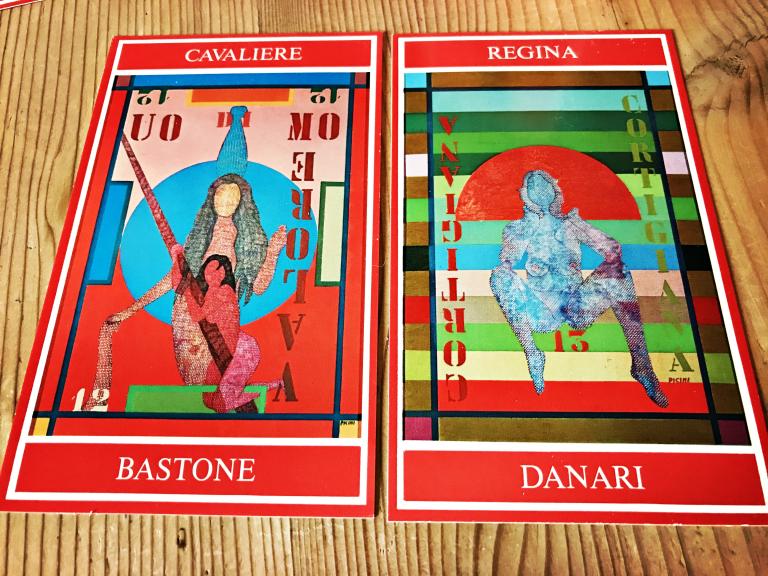

Two more cards fell on the table: The Knight of Batons and The Queen of Coins.

While turning them over I said the following: ‘It’s a classic. While no one ever speculates about how fat or thin their local grocery store’s bank account is, many are busy with yours. What you need to do is ride your broom, and move at considerable speed to make your own money. All those who have time to speculate on how you make your living will not be able to see how fast you move. And speed is important, especially if you have to wield the King of Spades’ sword so you can sit comfortably under the hot sun.’

‘Oh, wow, all this from these cards…’ the person said in awe, to which I replied: ‘Yes, we read the cards like the Devil, though the latter part comes from the war manuals and martial arts that I’ve beed studying.’

The point of this exchange is to demonstrate the power of looking at what we do with the cards, not what we know. A lot of what we know is pure nonsense.

In the case of Andrea Picini’s Diavolo deck, let me quote at random Ugo Moretti, the writer of the book that comes with the cards (both in art book form and as a booklet accompanying the deck).

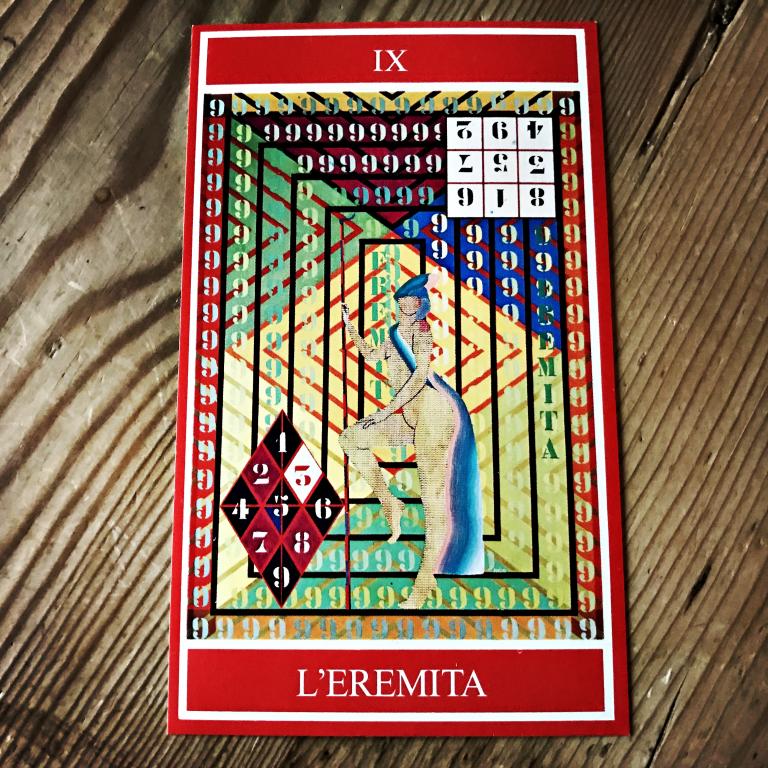

Here’s what he thinks the Hermit is:

‘He is without curiosity and heeds only ponderable factors. He is a meditative spirit, rigidly logical. Arid. Masturbator, misanthrope. Methodic, not empiric. Taciturn, energy-saving, Monotonous. A conserver of goods, able in appropriating others’ belongings. This is the Card of Stockbrokers, Real Estate Speculators, Middlemen, Procurers.’

Now, this is a whole lot of ‘The Hermit is’… I want to say, ‘what Devil has gotten into Moretti’s head, for it sure as hell isn’t Picini’s Diavolo…’

In his visual rendition, the Hermit is a woman who is good at magic squares and numbers.

So much for meaning, naming, and proclaiming.

If you read cards, look at them and think in terms of who does what to whom. You may just discover that, on occasion, the Magician is not about mostly male inventiveness – ‘an architect, engineer, constructor, urbanist, chess player’ à la Moretti – but rather about picking the relevant tool on his table to prick his enemies with.

Thinking about intangible powers is not the same as being specific with your actions. If an image is well crafted, it will tell you what the obvious is, and it’s almost never a list of random keywords. Cards are fantastic tools for identifications, and there’s nothing like a good relatability fad, but if you want to render someone real service, the last thing you’ll do is place the cards in their face as mirrors, while going without discernment: ‘you are like this, your enemy is like this, your children are like this, your body is like this, your mother is like this, your boss is like this…’

Nothing is ever ‘like this’ by virtue of the law of impermanence. In this hall of mirrors, the only real option available to you is to look at what you do.

♠

Stay in the loop for cartomantic activities.