I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the difficulty of arguing with very traditional Catholics about elements of the Catholic faith. I often find myself in a position where I’m clearly able to see the problem with a particular argument – but I don’t know how to articulate it in a way that my interlocutor will understand. I have too many postmodern axioms and influences – axioms which I retain because they are true and compatible with the faith, but which are none-the-less foreign to traditional Catholic thought.

It’s one of the pitfalls of being a convert. When someone converts to Catholicism, they will always bring with them certain habits of thought that they’ve learned from whatever background they happen to have come from.

For example, when you read stuff written by Protestant converts you often find a tendency towards Biblical literalism and proof-texting. Converts may continue to quote from respected Protestant theologians, particularly when the theology in question is compatible with or adds on to Catholic theology. They’re liable to have a deep and abiding interest in questions about the relationship between grace and salvation, predestination, and the Marian doctrines.

None of this means that they’re “less Catholic” than cradle Catholics, it just means that they are bringing Protestant ways of thinking into the Church, participating in the great historical project of “reconciling all things in Christ to make them new.”

Apart from a few ultra-Catholic fanatics, most people are perfectly comfortable with this when it comes to Protestantism. After all, Protestants are our “separated brethren.” But when it comes to converts from other backgrounds, there can be a lot more suspicion.

While Protestant modes of thinking are generally acceptable, there’s otherwise a kind of an underlying assumption that if you are a “real” Catholic thinker then you will think like a Catholic. That is to say, your background will consist largely in reading a certain cannon of accepted Catholic texts. You’ll be familiar with Thomistic thought, probably familiar with Aristotelean ideas (even if you didn’t learn them as such), there’ll be some G. K. Chesterton, the writings of various doctors of the Church, and some C. S. Lewis thrown in for good measure. Add a smattering of Augustine if you’re serious about theology, a bit of Plato if you’re more philosophically minded, and a lot of Therese of Lisieux if you’re drawn to piety. (The serious Catholic intellectual will also have read about 1D20 Vatican documents, focusing on whatever areas of the faith are of greatest particular to concern to himself.)

There’s nothing wrong with this intellectual program – but it does become a problem when Catholics assume that these foundational texts form the basis for more or less all intelligent engagement. It’s not that anyone imagines that most people are actually familiar with these works, but rather that there’s a tendency to believe that this way of thinking is basically normative, and that the styles of argument which this course of reading produces are the only valid form of human discourse for those who are in pursuit of truth.

It’s particularly problematic for converts who enter the faith from secular intellectual backgrounds. In her excellent book Getting to Amen, Leah Libresco talks about the experience of being a convert with no Christian background as being like learning a new language. I think it’s an apt metaphor. When you first become a Catholic there’s an absolutely huge amount of vocabulary and grammar that you have to try to internalize in order to practice the faith. But more than that, there are ways of thinking that are quite alien.

For example, for a lot of cradle Catholics belief in the authority of the Church is kind of fundamental. Maybe there have been moments of doubt, or even periods of time away from the fold, but at the bottom people’s reason for believing is something along the lines of “Where else would we go? You have the words of eternal life.” Protestant converts, similarly, often accept the Church’s authority because they’ve come to believe that Catholicism is more biblical than their old congregation. In both cases, the authority of the Christian tradition is a given, and everything else follows from it.

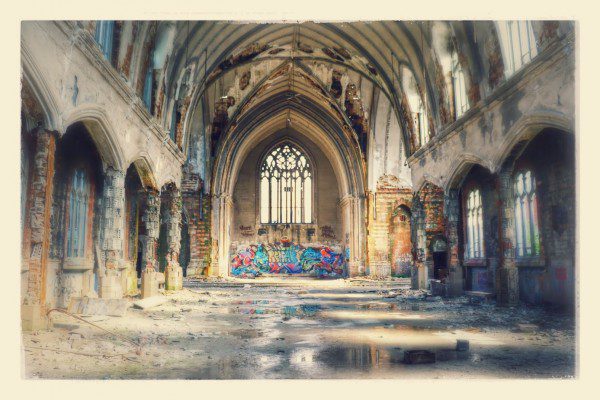

For a convert like me, it’s impossible that either of these two foundations will ever become the absolute bedrock of my thought. I became a Catholic via Kierkegaard’s philosophy of faith, Sartre’s ethics of authenticity, Dostoevsky’s theology of suffering and Keats’ poetic identification of the Beautiful and the True. It was my feminism that led me to Our Lady, my concern for the marginalized that drew me to Catholic ethics, and my Canadian respect for diversity that made me long for a truly catholic community. I can’t just kick out those pillars of my thought in order to have a more “pure” Catholicism, because without those axioms I no longer have a compelling reason for belief. I can purify and transform these foundations in the light of Catholic theology, but I can’t do away with them any more than you can remove the ground underneath a Cathedral and expect the superstructure to remain intact.

The bottom line is, no matter how fluent you become in a second language it is never your first. When you talk in your sleep, or you mumble incoherently on your death-bed, you will tend to revert to your native tongue, even if you hate your homeland.

This might seem to suggest that conversion is impossible: once a Catholic, always a Catholic – and once an atheist, always an atheist. Of course that conclusion is entirely unacceptable within Catholic thought, so something else has to be true.

I think that the truth is that the form of thought that people consider to be “Catholic” – the axioms that you get from Aquinas and Chesterton et al. – is not essentially Catholic. Actually, that’s pretty obvious: if you look at each of those thinkers it’s clear that Augustine is a converted Platonist (and still has a Platonic turn of thought), that Aquinas is an Aristotelean, that John Paul II is a continental phenomenologist, and so on, and so forth. Thinking like a Catholic homeschool kid, or a graduate of a Catholic private school that uses a classics-centered curriculum, is not actually conterminous with thinking “like a Catholic.”

Catholicism, on the contrary, is not merely a particular thought-language, a canonical set of stylistics for playing the game of truth. Rather, it’s meant to be a means of reconciling all of the different possible language games that will emerge through the process of history in order to make each of them cry out in praise of Truth Himself.

Becoming a Catholic convert does mean that you have to learn at least some of the traditional language of Catholicism as it exists, but it doesn’t mean that you have to entirely repudiate your personal intellectual heritage. Rather, you baptize it and allow Christ to transform it so that new and different facets of the infinite Godhead may be made manifest in our thought.

Image courtesy of Aaron Harburg