I just did my most fun interview ever. For once someone wanted to know about something other than what it’s like to be Catholic and gay.

– Would you call yourself an ‘ex-Stoic’? What were the best and worst aspects of living a dedicated Stoic life?

I generally use the term “recovering Stoic,” mostly because it amuses me — but also because I’ve always had a fairly deep-seated inclination towards Stoicism, even when I didn’t have a lot of knowledge of Stoic philosophy per se.

Far and away the best aspect of living Stoicism is the detachment. There’s a very real high that comes from being able to just deal with whatever happens, with knowing that you’re basically impervious to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, with being able to look down on your emotions from a vantage point of cultivated objectivity and kind of maneuver them around to get the effects that you want. I have a t-shirt that I made which reads “Stoics Have More Fun.” The logic of it being that if you’re a Stoic you can have fun with all kinds of experiences that people usually think of as unpleasant. Being massively stressed out as a Stoic is kind of neat. Giving birth as a Stoic is a serious trip. Because all of your emotions and sensations are externals — they’re not a part of you and they’re basically value-neutral — there’s an incredible kind of freedom that comes with that.

And probably the worst thing about Stoicism is the detachment. The longer that you practice it, the easier it is to just not give a damn. I don’t mean that you behave immorally — being exactingly moral is an important part of the deal. I mean that you’re kind of skimming along over the top of human experience, interacting with it largely in the abstract. It makes it harder to relate to other people because their problems don’t make sense. You can be scrupulously kind and considerate, forgiving, patient, attentive — but real compassion becomes harder and harder because feelings are just problems that you can fix. So when other people are experiencing emotional pain it kind of feels like they’re voluntarily torturing themselves and you want to show them how to stop doing that rather than entering into their suffering and sharing it with them. And then also, you can end up absorbing a lot of damage to yourself because you can just take it, and it doesn’t matter. Until one day it does matter, and you crash.

– Stoicism is criticised as dry, rational and self-centred. But Stoics protest that it’s about managing emotions rather than shunning them, and that their tradition has a lot to say about friendship and one’s connection with the rest of humanity. Does that show that, really, there are lots of Stoicisms?

Well, there’s the pop meaning of stoic, which is basically “unfeeling” — you know, the silent tough-guy who takes it all on the chin. But that doesn’t really have all that much to do with Stoicism as a philosophy. Stoicism isn’t repression, and it’s not being emotionless. It’s a set of very powerful techniques for shaping your interior life by pulling up a lot of the stuff that usually remains in the subconscious into the conscious realm where you can manipulate it using your reason and your will.

Friendship, especially, is really highly valued in Stoicism because it’s the least embodied form of love. It allows you to have close, reliable relationships without having to deal with intense emotional entanglements. Basically, you can have intimacy but it’s fairly low-risk. Stoicism sees friendship as the best form of human love because it’s the least passionate: it’s based on more intellectual values like common interest, mutual accord, a shared pursuit of virtue. It works better for men, of course, because women’s friendships tend to be more emotional – if you’re a woman trying to be a Stoic you basically end up making friends with guys.

As for connection to the rest of humanity, yes, definitely. One of the really beautiful things about Stoicism is the sense that you’re a part of something much larger than yourself. Part of the way in which your problems don’t matter is that they’re recontextualized within a broader human scheme: you’re just a small part of a much larger entity. A social entity, at the lowest level, a cosmic one above that. So care for the community, a sense of obligation and duty, a desire to contribute to human flourishing on a grander scale, those are all definitely a huge part of the Stoic lifestyle. If you took that away you would have a very inhuman and narcissistic philosophy – which is what a lot of people who don’t know much about it imagine Stoicism to be.

– Stoicism was the inspiration for CBT, which is not uncontroversial but seems to get good results, even help people get over serious crises. Is that empirical proof that Stoicism works?

Well of course it works. It’s hugely powerful. And if you look at a lot of early Christian writing, you can see the Church fathers taking the techniques of Stoicism and integrating them into a Christian worldview, in much the same way that a lot of churches today incorporate psychotherapeutic approaches into pastoral care. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy basically takes Stoic technique, divorces it from Stoic philosophy, and then applies it — often with very dramatic results. And really, I think there’s a lot to be gained by having Stoic practice as a part of your interior tool-kit, because there are situations where various Stoic disciplines are definitely both effective and appropriate. Where you get into problems with Stoicism — and I think this is the case with every philosophy — is when it becomes the entire tool-kit. You know, you can think of it as being in the same category as something like Marxist analysis, social constructionism, Aristotelian categories — all of those tools are amazingly effective if you apply them to the right kind of problems, but when you allow any particular philosophical method to become a worldview unto itself that’s when you end up generating problematic nonsense.

– Some Christian thinkers have regarded Stoicism as a kind of delusion; others –Simone Weil, for instance – see it as expressing a deep piety which makes it the closest of all philosophies to Christianity. Who’s right?

It depends on which aspects of Stoicism you’re concentrating on. There’s definitely a very profound piety in traditional Stoicism, and to a large degree Stoicism and Christianity are very sympatico. Both seek to situate the human person within a larger, divinely ordained context. Both promote the cultivation of virtue — and identify a lot of the same behaviours as virtuous or vicious. Both seek to free the person from enslavement to appetites and passions. And there does seem to have been a certain amount of mutual respect between Christians and Stoics, at least for a while. Epictetus, for example, speaks with great admiration for the “Galilean” martyrs, and uses them as an example of how it’s possible to have interior freedom even in the face of death. And of course the notion of apatheia was very important in a lot of the writings of the Church Fathers, especially in the East.

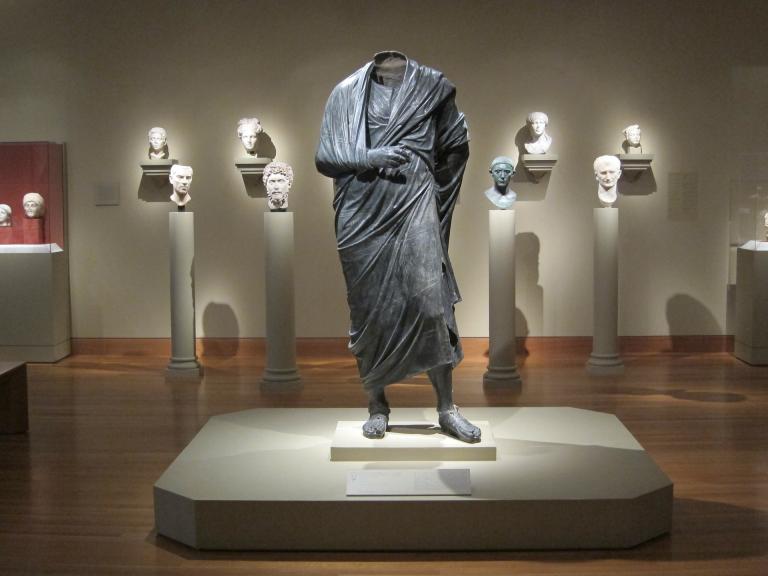

But then, there were significant persecutions of Christians under the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius — basically because Stoicism sees the social order in this world as the higher good towards which individual human life is ordered, whereas Christianity looks towards the eschatological transformation of society in the Communion of Saints. Also, God in Stoicism is imminent, whereas God in Christianity is a transcendent Being who becomes immanent through the Incarnation. And Stoicism posits human perfection through moral effort and self-discipline, whereas Christianity promises salvation through grace. So there are these very fundamental differences as well.

Image credit: