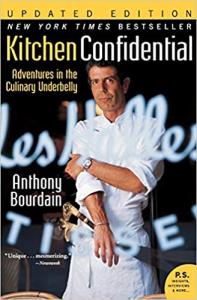

Kitchen Confidential

by Anthony Bourdain

New York: HarperCollins, 2017 (First Harper Perennial Edition)

312 pages, $8.99

“I’m asked a lot what the best thing about cooking for a living is,” Anthony Bourdain writes at the beginning of Kitchen Confidential. He gives a number of conventional reasons—“to be part of the subculture,” a “secret society with its own language and customs,” “making something good with one’s hands”—before he gets to the chief reason:

It can be, at times, the purest, most unselfish way of giving pleasure (though oral sex has to be a close second).

It would be TMI for me to provide a direct reaction to the oral sex part, so I won’t. But I can confirm the claim of unselfishness. For example, I remember the one (and only) time I made a brisket. Not the Texas/Kansas City kind. The Jewish kind, which I learned about from the Amazon Prime series, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. The first thing you have to know is, this isn’t pot roast, which main character Midge Maisel scoffs at as “the Methodist version of brisket.”

I spent hours preparing it for my family: buying ingredients, mixing them according to the complex recipe I found online. Then, waiting patiently while it roasted in the oven (just six hours, not the gazillion hours needed for Texas/Kansas City brisket).

It was divine. We feasted that night and munched leftovers for the rest of the week. But aside from those leftovers, in a few minutes, it was gone. Nothing left but crumbs—and full, satisfied bellies.

I had given pleasure, which for me was the most pleasing thing about the experience.

Good food done well

One of my favorite things about Mr. Bourdain in Kitchen Confidential is how unpretentious he is. Yes, he was a world-renowned chef who knew how to appreciate (and prepare) a gourmet meal made in the kitchen of a Michelin starred restaurant, but what he loved even more were good meals prepared well and with love.

On my day off, I rarely want to eat restaurant food unless I’m looking for new ideas or recipes to steal. What I want to eat is home cooking, somebody’s—anybody’s—mother’s or grandmother’s food…. My mother-in-law would always apologize before serving dinner when I was in attendance, saying, “This must seem pretty ordinary for a chef…” She had no idea how magical, how reassuring, how pleasurable her simple meat loaf was for me, what a delight even lumpy mashed potatoes were.

And he has no time for any cook who approaches cooking as an art, not as craft. An artist “is someone who doesn’t think it necessary to show up at work on time.” But cooking, he writes:

… is a craft, I like to think, and a good cook is a craftsman—not an artist. There’s nothing wrong with that: the great cathedrals of Europe were built by craftsmen—though not designed by them. Practicing your craft in expert fashion is noble, honorable, and satisfying.

Cooking as craft

I am not yet halfway through Kitchen Confidential. Just about every word in this semi-autobiography demonstrates what Mr. Bourdain means about cooking being craft: how he fell arse-backwards into the restaurant business by getting a job as a dishwasher in a Provincetown, Mass., restaurant one summer; how he learned the ropes in a typical kitchen; to how he dropped out of college the following year and enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America; the eccentric collection of misfits and geniuses he got to know as a professional cook, and so on.

Mr. Bourdain spends little time on his childhood except to tell anecdotes about two key food-related moments, one involving soup and the other involving raw oysters (his experience with his first oyster is remarkably similar to my own, though he enjoyed it more than I did). He gives the down-and-dirty on what to order and not to order in restaurants (never order fish on a Monday; pay attention your wait person’s body language).

But what mostly comes through, here as in Mr. Bourdain’s CNN series, Parts Unknown, is love: love of food; love of craft; love of the people he meets in the amazing world of professional cooking, with its testosterone-fueled hierarchy of “dysfunctional, mercenary fringe-dwellers” who, nonetheless, night after night, perform “a high-speed collaboration resembling, at its best, ballet or modern dance.”

June 8 was the three-year anniversary of Mr. Bourdain’s tragic death. May he rest in peace.