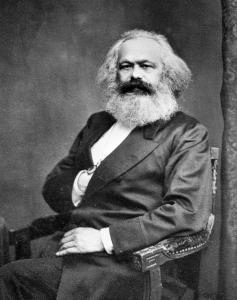

When Pope Leo XIII wrote Rerum Novarum [1] in 1891, the world had seen the dire impact of unregulated capitalism on working people. It was, therefore, obvious to the Pontiff “that some opportune remedy” needed to “be found quickly for the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class….” (Ibid, §3) A system had developed such that “the hiring of labor and the conduct of trade” were “concentrated in the hands of comparatively few; so that a small number of very rich men” had “been able to lay upon the teeming masses of the laboring poor a yoke little better than that of slavery itself.”

Leo XIII’s solution would be a requirement that wages be sufficient to support a family, with labor unions to secure that right, combined with assistance from the State if needed. But he also addressed the remedy proposed by the socialists of his day, which he rejected completely. But what, precisely, was he rejecting? He explained it plainly:

Leo XIII’s solution would be a requirement that wages be sufficient to support a family, with labor unions to secure that right, combined with assistance from the State if needed. But he also addressed the remedy proposed by the socialists of his day, which he rejected completely. But what, precisely, was he rejecting? He explained it plainly:

“To remedy these wrongs the socialists, working on the poor man’s envy of the rich, are striving to do away with private property, and contend that individual possessions should become the common property of all, to be administered by the State or by municipal bodies. They hold that by thus transferring property from private individuals to the community, the present mischievous state of things will be set to rights, inasmuch as each citizen will then get his fair share of whatever there is to enjoy. But their contentions are so clearly powerless to end the controversy that were they carried into effect the working man himself would be among the first to suffer. They are, moreover, emphatically unjust, for they would rob the lawful possessor, distort the functions of the State, and create utter confusion in the community.” (Ibid, §4)

What Leo XIII was opposed to was the abolition of private property. Here, it should be noted, that the “private property” referred to wasn’t individual items for personal use, but the means of production, or capital goods, such as machinery, factories, or the soil. But why did Leo XIII believe that working people “would be among the first to suffer” if private ownership of the means of production was abolished? He laid it out like this:

“It is surely undeniable that, when a man engages in remunerative labor, the impelling reason and motive of his work is to obtain property, and thereafter to hold it as his very own. If one man hires out to another his strength or skill, he does so for the purpose of receiving in return what is necessary for the satisfaction of his needs; he therefore expressly intends to acquire a right full and real, not only to the remuneration, but also to the disposal of such remuneration, just as he pleases. Thus, if he lives sparingly, saves money, and, for greater security, invests his savings in land, the land, in such case, is only his wages under another form; and, consequently, a working man’s little estate thus purchased should be as completely at his full disposal as are the wages he receives for his labor. But it is precisely in such power of disposal that ownership obtains, whether the property consist of land or chattels. Socialists, therefore, by endeavoring to transfer the possessions of individuals to the community at large, strike at the interests of every wage-earner, since they would deprive him of the liberty of disposing of his wages, and thereby of all hope and possibility of increasing his resources and of bettering his condition in life.” (Ibid, §5)

“It is surely undeniable that, when a man engages in remunerative labor, the impelling reason and motive of his work is to obtain property, and thereafter to hold it as his very own. If one man hires out to another his strength or skill, he does so for the purpose of receiving in return what is necessary for the satisfaction of his needs; he therefore expressly intends to acquire a right full and real, not only to the remuneration, but also to the disposal of such remuneration, just as he pleases. Thus, if he lives sparingly, saves money, and, for greater security, invests his savings in land, the land, in such case, is only his wages under another form; and, consequently, a working man’s little estate thus purchased should be as completely at his full disposal as are the wages he receives for his labor. But it is precisely in such power of disposal that ownership obtains, whether the property consist of land or chattels. Socialists, therefore, by endeavoring to transfer the possessions of individuals to the community at large, strike at the interests of every wage-earner, since they would deprive him of the liberty of disposing of his wages, and thereby of all hope and possibility of increasing his resources and of bettering his condition in life.” (Ibid, §5)

If the means of production cannot be privately owned, they cannot be privately purchased. But wages are earned precisely to be used in subsequent purchases. But if a working person cannot invest whatever savings he has into some form of capital ownership, his purchasing power has been to that extent reduced, and, thus, the value of his wages. Some will point out that wages are often so low that there isn’t any money left over for investment anyway. But it is those low wages that Leo XIII identified as the locus of the injustice in unregulated capitalism. The answer, he held, was to elevate working people to where they could be meaningful participants in the economy, not assign all meaningful participation to the State.

The Pontiff also objected to abolition of private property in the means of production on the ground that it constitutes a violation of natural law. I will explore that in the next installment in this series.

The icon of St. Joseph the Worker is by Daniel Nichols.

Listen to Christian Democracy on live internet radio on Tuesdays at 10:30 p.m. Eastern time at WCAT Radio here, or listen to the podcast here on the Christian Democracy Patheos blog.

Please go like Christian Democracy on Facebook here. Join the discussion on Catholic social teaching here.