At the end of last month your humble servant wrote an article entitled “The People Should Elect the Bishop,” [1] which got a fair amount of attention, and some objections were raised that require a response. Even though it is an old idea, for those of us living in these times it is a new idea, and it is not surprising that some objections would be raised. People are accustomed to what they are accustomed to, and practices which precede one’s lifetime can often carry with them the illusion that they stem from eternal verities.

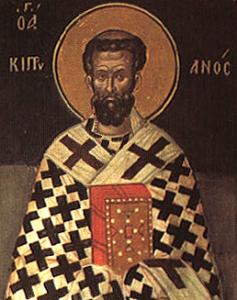

And one objection that was raised was that I was proposing a change in the very nature of the Catholic Church, that I was even suggesting a move in the direction of Protestantism. But nothing could be further from the truth. The fact is, in the early Church, popular election of bishops was a common practice. The chief witness to the practice is St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage in the 3rd century. As Patrick Granfield of Catholic University of America put it,

“In the Roman Catholic communion today the writings of Cyprian are referred to with increasing frequency and approval. This is especially evident in contemporary research on the nature of episcopal ministry and on the coresponsibility of all levels of Church membership. The witness of Cyprian is important at a time when demands are being made for structural reform and greater democratization of the Roman Church. Cyprian furnished valuable information on the practical operation of shared responsibility in the election of bishops. He stated emphatically that the entire community—clergy, laity, and neighboring bishops—should participate in the selection of episcopal leaders. In this he anticipated the important assertion made by Leo the Great two centuries later: ‘Qui praefuturus est omnibus, eligi debet ab omnibus.’” [2]

“In the Roman Catholic communion today the writings of Cyprian are referred to with increasing frequency and approval. This is especially evident in contemporary research on the nature of episcopal ministry and on the coresponsibility of all levels of Church membership. The witness of Cyprian is important at a time when demands are being made for structural reform and greater democratization of the Roman Church. Cyprian furnished valuable information on the practical operation of shared responsibility in the election of bishops. He stated emphatically that the entire community—clergy, laity, and neighboring bishops—should participate in the selection of episcopal leaders. In this he anticipated the important assertion made by Leo the Great two centuries later: ‘Qui praefuturus est omnibus, eligi debet ab omnibus.’” [2]

Moreover, this was at least a widespread practice, if not universal.

“The geographic extension of the elective process described by Cyprian is quite broad. It appears, as we have seen above, to have been the ordinary and normal way of electing bishops in at least three important Christian centers: Rome, Spain, and Africa. Cyprian referred to his own election, at which he was chosen bishop ‘populi universi suffragio.’ He also stated that the custom of popular election was observed not only in Africa (‘apud nos’) but ‘fere per provincias universas.’”

So popular election of bishops is hardly an innovation, much less a Protestant innovation. It is simply the way that many of the early churches selected their bishops. Anyone opposed to the idea has to do better than “the Church is not a democracy” bromide. He will have to give reasons for why he thinks it is a bad idea.

An objection along those very lines also came up. Many were concerned that Catholics will willfully elect heretics. To that objection I have two responses.

The first is simply that I can’t imagine how we could do worse than leadership that allows a manifest pedophile ring to flourish throughout the world. Worse, they cover it up. All meaningful impetus for reform has come from outside their ranks.

Secondly, those who are concerned that the Church will somehow change her essential doctrines have forgotten about the Holy Spirit. Elected bishops, who will be as duly ordained as the bishops we have now, won’t be a different kind of creature. If they agree in an ecumenical council, the Holy Spirit will ensure the results as surely as he does now. Human beings cannot overcome the teachings of the Church. It is impossible.

Secondly, those who are concerned that the Church will somehow change her essential doctrines have forgotten about the Holy Spirit. Elected bishops, who will be as duly ordained as the bishops we have now, won’t be a different kind of creature. If they agree in an ecumenical council, the Holy Spirit will ensure the results as surely as he does now. Human beings cannot overcome the teachings of the Church. It is impossible.

But we can certainly try to devise a way to select bishops who will behave better. I humbly submit that we can do that by returning to the early practice of the Church.

The icon of St. Joseph the Worker is by Daniel Nichols.

Please go like Christian Democracy on Facebook here. Join the discussion on Catholic social teaching here.