There’s talk that the United States will be going to war in either Iran, Venezuela, or both, and so we’ll have to take a look at the prospect in light of Catholic teaching. It’s really not a close question, as might be suspected in advance, but it is worthwhile to set out fully why attacking either country would be a serious breach of the Fifth Commandment.

Let us first set forth the just war doctrine as articulated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

“The strict conditions for legitimate defense by military force require rigorous consideration. The gravity of such a decision makes it subject to rigorous conditions of moral legitimacy. At one and the same time:

“—the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain;

“—the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain;

“—all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be impractical or ineffective;

“— there must be serious prospects of success;

“— the use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated. The power of modern means of destruction weighs very heavily in evaluating this condition.

“These are the traditional elements enumerated in what is called the ‘just war’ doctrine.

“The evaluation of these conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment of those who have responsibility for the common good.” (Ibid, No. 2309) [1]

We’ll look at each of the four factors individually, but first it should be pointed out that these criteria are to determine the grounds for “legitimate defense by military force….” That’s “defense,” with a “d.” There is no question of simply attacking another country. An attack on the United States, or on a country with which we have a mutual defense treaty, is a condition precedent for going to war legitimately.

What should be made clear initially is that each of the four factors must be satisfied at “one and the same time….” All four criteria must be met simultaneously. Meeting three or less of them is insufficient.

The first criterion is that “the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain….” Venezuela right now is no threat to anyone, other than itself. Iran, on the other hand, presents a different picture. Its support for terrorism abroad is well documented [2], and anyone claiming that Iran is not a destabilizing force, particularly in the Middle East, would have a tough case to make. The damage it inflicts on the community of nations is an ongoing problem, there is no indication it will stop any time soon, and it involves the loss of life.

The second criterion requires that any other means of dealing with the problem are demonstrably futile. Venezuela is chiefly a problem for itself. Iran’s toxic reach is well established, but there really has been no serious effort to resolve the problem diplomatically.

The second criterion requires that any other means of dealing with the problem are demonstrably futile. Venezuela is chiefly a problem for itself. Iran’s toxic reach is well established, but there really has been no serious effort to resolve the problem diplomatically.

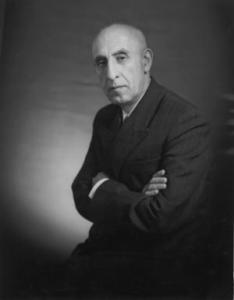

If it seems self-evident that Iran cannot be approached with the use of reason, the history of that situation ought to be considered. The early 1950s U.S. involvement in the overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddeq, Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, should be kept firmly in mind. [3] This effort, which also involved the British, was “aimed at making sure the Iranian monarchy would safeguard the west’s oil interests in the country.” The incident is a reason given for Iranian mistrust of American and British politicians to this day. Notwithstanding our differences, it seems that the United States wouldn’t lose too much face by opening negotiations with a formal apology for engaging in something so palpably wicked.

As for there being “serious prospects of success,” it is difficult to imagine that Venezuela will present much of a military problem for the United States, at least when it comes to toppling the existing regime. But the American military hasn’t fared particularly well when it comes to asymmetric warfare. This is no knock on our men and women in uniform; no one is very good at it. And socialists have proven at least as effective at asymmetric warfare as Muslims. Vietnam taught the world a lesson: don’t give up, keep coming, and, even if you lose every battle, the United States will get tired of it eventually. The Taliban have been practicing this method for some time now in Afghanistan. If the socialist forces in Venezuela adopt this method, it could be another long haul for the United States.

Even more would this be true for Iran. First of all, toppling the regime would be no cakewalk. Secondly, Hezbollah, an Iranian proxy, has demonstrated its ability to be a continuing thorn in the flesh. Should the U.S. invade Iran, one imagines that the regime will eventually fall. But the Iranian genius for organizing militant groups would make our stay there a long and onerous one. Indeed, American impatience would likely cause this war effort to end in failure.

Finally, we must consider whether an invasion of Venezuela or Iran would “produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.” Even if Venezuela acquiesces, an invasion of Iran promises a combative occupation, probably lasting more than a decade, and devastating the country. American air power will once again cause civilian casualties, perhaps reaching into the hundreds of thousands.

Finally, we must consider whether an invasion of Venezuela or Iran would “produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.” Even if Venezuela acquiesces, an invasion of Iran promises a combative occupation, probably lasting more than a decade, and devastating the country. American air power will once again cause civilian casualties, perhaps reaching into the hundreds of thousands.

Moreover, American citizens should consider what more wars of choice will do to the United States. More billions will be poured to the continuous war effort, while our infrastructure continues to crumble, our schools languish, and the social safety net fades into memory. And this will happen because we chose to engage in elective wars against regimes which presented no real threat to us.

The just war doctrine does not support going to war with either Venezuela or Iran. Yet we look on with a measure of despair, because, even if we know that doing so will operate against our best interests, we feel that we have no say in the matter. The evaluation of the conditions for a just war “belongs to the prudential judgment of those who have responsibility for the common good,” and their judgment in recent decades hasn’t inspired confidence. Nonetheless, if the president decides to go to war, we’ll go to war. Simple as that.

But that isn’t leaving the judgment to those responsible for the common good.

Hopefully not too many will consider this a mere technicality, but, under the Constitution, the president doesn’t really have the authority to initiate a war. That power resides with Congress, according to Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. [4] It is true that the president is the Commander in Chief of the armed forces under Article II, Section 2, but that doesn’t authorize him to initiate a war without a congressional authorization.

Hopefully not too many will consider this a mere technicality, but, under the Constitution, the president doesn’t really have the authority to initiate a war. That power resides with Congress, according to Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. [4] It is true that the president is the Commander in Chief of the armed forces under Article II, Section 2, but that doesn’t authorize him to initiate a war without a congressional authorization.

Now it is true that presidential war making has only been checked by the rather toothless War Powers Resolution [5], but the Constitution is the supreme law of the land. It cannot be overridden by statute, or congressional acquiescence to an unconstitutional practice. Those responsible for the common good in this context is Congress. Without authorization from that body, military action against Venezuela or Iran will be illegitimate.

Of course, as we have seen, it will be morally illegitimate even if Congress approves.

The icon of St. Joseph the Worker is by Daniel Nichols.

Please go like Christian Democracy on Facebook here. Join the discussion on Catholic social teaching here.