As you well know by now, I’ve been working through a bunch of books on my to-read shelf. As a history enthusiast, I was delighted to finally pick up Michelle Duster’s book, Ida B. the Queen.

Can’t remember how Ida B. Wells changed the course of American history? Let me (or the back of the book, as luck would have it) remind you: “Journalist. Suffragist. Antilyncing crusader. In 1862, Ida B. Wells was born enslaved in Holly Springs, Mississippi. In 2020, she won a Pulitzer Prize. Wells committed herself to the needs of those who did not have power. In the eyes of the FBI, this made her a “dangerous negro agitator.” In the annals of history, it makes her an icon.”

For Duster, who’s also the great-granddaughter of Wells, this is not merely family lore. Instead, it’s telling the story only she alone can tell (that something I can attest to after publishing my first book, The Color of Life, which is about my father-in-law, James Meredith).

Although the book is geared toward a young adult audience, I loved getting to know more about how Wells left her mark on history. As it goes, the second half of the book steered away from the aforementioned queen and focused on a whole bunch of noteworthy Black folks.

This only left me wanting more of the queen herself!

Of course, one of the main ways I interacted with the book came after reading this paragraph here:

Speaking out about injustice can be a lonely experience and often comes with the loss of things that one holds dear. But the question must be asked: Is it better to be silent and endure hardship, or is it better to speak out and possibly effect change? Standing out and speaking out alone is something few are willing to do. And the ones who do often become history makers, as Ida has. The attention she has gained posthumously surpasses the level of appreciation that she experienced while alive. During her life she was considered so controversial and “militant” that many times she stood alone (100).

This whole idea of speaking out to effect possible change is one I think about often. As a writer, and specifically as a writer who finds a home in the Christian tradition, I can’t not see threads of justice (and its opposite, injustice) in the world around me.

I have not always gotten it right, that much is true, but in recognizing my privilege, I have tried to use my platform to speak out against injustice and possibly enact change along the way too.

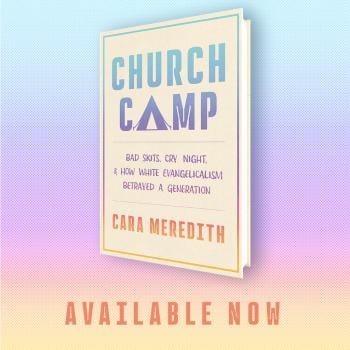

This happened in and with my first book, The Color of Life, particularly when it came to issues of justice, race, and privilege. I would argue this is a major theme in my second book, Church Camp, specifically when it comes to the injustice experienced by and caused toward women, people of color, and the LGBTQ+ community.

It’s not hard to see the loss I’ve experienced in this journey, particularly when it comes to relationships. Because both of my books deal with issues that are at the core of white evangelical identity, and, one can argue, that also create ideological divisions of belonging within evangelicalism, when I have not towed the line within accepted belief systems, I have caused strife.

When I have believed that women are just as brilliant and equally deserving as men, and should therefore receive more than mere complementarian props for the casseroles they cook and the Vacation Bible School set designs they create, I draw a line in the sand. I lose friendships because I am not following the rules.

When I have believed that people of color are created in the image of God, a God, mind you, that is not and has never been white, and a God that delights in the robust diversity of creation, I sow seeds of division. One need not look farther than the current administration’s stance toward all things DEI to see how this is true.

And when I have believed that the LGBTQ+ community is just as beloved, just as valued, just as worthy of belonging in the kingdom of God as those who happen to live in cisgender bodies or love those of the opposite sex, I create division. I embody “woke” rhetoric that has no place in orthodoxy.

But then, as often is the case, I also remember that this is not necessarily (usually, always) about me.

It’s about those in need of change, whose privilege does not afford them the same rights I may innately carry in my body.

So, I speak up, even if it feels a little scary, even if I don’t know what’s going to happen on the other side.

And I sure am glad Ida B. the Queen reminded me of this very thing.

Same for you?

*Post contains Bookshop Affiliate links.