We might hear talk of “politics and religion” either in conflict or one maybe tainting the other, but what’s really at hand is a conflict of worldviews and the truths behind them, and the conflicts, considered impartially, are usually between two perspectives that are in themselves good. Take three examples: abortion, free speech on campus, and female genital cutting, a practice common in parts of north Africa. The abortion debate at root is a conflict between the truth that human life is sacred and the truth that all persons have a right to self-determination. The free speech on campus debate is a conflict between the truth that persons have a right to express their beliefs freely and the truth that groups who have historically experienced marginalization or victimization have a right to be protected from hurtful messages. The female genital cutting debate, likely abhorrent to many readers, is a conflict between the truth that all persons, particularly children, have a right to be protected from bodily harm without their consent and the truth that traditional cultures have a right to be protected from the imposition of Western values, which to great degree have been disseminated through colonialism and imperialism. What we usually call “politics” is merely the public arena within which worldviews conflict, and often one or more of the worldviews in a given conflict has its foundations in truths or axioms that come from religious belief. Many of the truths that undergird the world views of religious persons issue from or are connected to their conceptions of God.

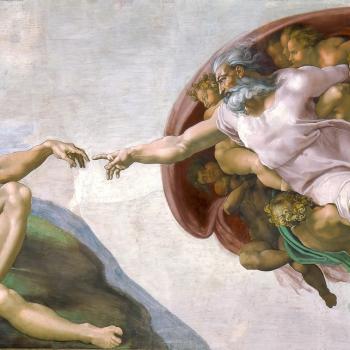

It has to be stated frankly that every conception of God we have is flawed. We might consider harboring no conceptions of God at all, which is not to say that there is no God, but is only to say that the nature of God so explodes our every attempt to think or speak about it that we remain silent. I doubt it occurred to those who dwelled on the image of God as judge that such an image psychologically enabled them to hang moral offenders from the gallows, say, in colonial America. Or those of us who still think of God in terms of “the highest”—that kind of thinking still has us subscribing to the Great Chain of Being, with humankind conveniently at the top of the earthly realm and all other creatures at the disposal, even whim, of our massive collective appetite for food and resources. The consciousness of a chicken or cow doesn’t count for much in a universe governed by an anthropomorphized God, who, by the way, as a male, has extended tacit consent for the subjugation of women through the ages. But probably the most problematic conception of God is “the all-powerful.” The Abrahamic god is surpassingly more powerful than any previously worshipped being; we aim to become, most often unconsciously, like that which we venerate, and obviously God is the most venerated being for most believing people. When we attribute omnipotence to divinity, do we not attribute divinity to omnipotence? It’s worth noting too that four of the nine choirs of angels in Christianity have titles associated with power: Thrones, Dominions, Powers, and Principalities. Like Phaethon, the son of Greek solar-deity Helios, who recklessly decides to take the reins of the sun from his father and scorches the earth, has our deification of omnipotence landed us at the control panel of nature, and have we not similarly scorched the earth?

One concept that I might associate with divinity is pain. Now that might sound strange. Isn’t pain the one thing we seek always to avoid, and isn’t pain the one certain characteristic of hell, the place from which God is absent? Perhaps we should have our understandings of heaven and hell turned upside-down, along with the notion that God could be absent from any place or world.

I arrived at the thought that pain is somehow characteristic of divinity because the theme of pain and suffering runs through the stories, words, and actions of numerous teachers and thinkers through the ages. I’ll share just three examples. The first example that occurs to me is Jesus of Nazareth. Notice that his ministry almost entirely hinges on addressing pain and suffering. He restores the sight of the blind, cures the diseased, heals paralytics, restores withered hands, and even more than this he addresses the anguish of the alienated and marginalized—be they lepers, prostitutes, despised tax collectors, or Samaritan women. And his campaign against the religious leaders of the day arose from his recognition that their system of laws and accounting of people’s sins kept so many otherwise good people trapped in the misery of being outcast by society. Centuries later, saints who made the imitation of Christ their top priority also sought to alleviate the suffering of others—I have in mind Francis of Assisi, Dorothy Day, and Saint Mother Teresa, all of whom saw divinity through suffering—that somehow holiness is found directly through those who suffer.

The second example of where I’ve seen this connection between suffering and divinity, though in a negative way, comes from Noam Chomsky, who, when asked whether he believes there is a god, responded that there are two possibilities: either there is no god, or if there is, he’s a devil. Now Noam is a good and brilliant man, so why would he respond so shockingly to the question? Chomsky, like Howard Zinn, is I think more deeply aware of the expanse and depth of suffering in the world than most people. In his mind, there cannot be any Being that is simultaneously all-powerful and benevolent. And unlike the author of the Book of Job or Dostoyevsky or Elie Wiesel or Rabbi Harold Kushner—all of whom attempted, among many others, to reconcile a good God with the suffering of innocents on earth—Chomsky just throws in the towel and says such a God, at least as we traditionally think of God, is evil or isn’t at all.

The final example of a thinker who contributed to, at least in my mind, the connection between divinity and suffering is Yuval Noah Harari, author of the recent, popular book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harari explains that one of the major reasons why human beings have been so successful as a species over the last several thousand years is our ability and willingness to abide by what he calls fictions—aspects of our lives that have no objective reality but are only believed in or trusted by so many people that their intersubjective weight almost lends them an objective reality. Examples include companies, nations, borders, deities, human rights, and—what Harari calls the most successful fiction in history—money. In an interview Harari was asked, if so much of what makes our experience of the world is fictitious, then can anything be called real? He paused for a moment and responded that the only thing we know with certainty is real is pain, and from this realization he says that we have a responsibility to address and abate all the pain and suffering in the universe that we can, which includes the enormous total pain and suffering we have inflicted and continue to inflict on non-human sentient beings.

Christians should be careful not to allow reflection and meditation upon the crucifixion to be overshadowed by the Resurrection. In the crucifixion, we see what seems an impossible juxtaposition—even intersection—divinity and suffering become one. I think that perhaps the image of the crucifixion is the most of God’s reality in pain and suffering that we can behold. I think no one would ever want to see God directly because in doing so one would see all the pain and suffering in the universe at once, since after all God, as love, “bears all things” and “endures all things.” If the universe exists in God, and at once God is the heart of all things in the universe, then God experiences all. The question then would be not why God made a universe that includes suffering, but why does God endure all the suffering of the universe?