No one would dispute the idea that Jesus has a way with words in his teaching. His teachings are life-giving and deeply profound. Jesus used language in many forms to teach: parables of the mustard seed, the leaven and the pearl, among others; His quintessential short story – The Prodigal Son; and, sayings, as in the Gospel of Thomas, “Those who seek should not stop seeking until they find. . .” and the Beatitudes, “Blessed are the poor in Spirit. . .,”each its own deep well of inspiration and truth. But there is one occasion in the Gospels, I believe, when Jesus offered something very different. It was in response to a request from his apostles, “Lord, teach us how to pray.” On this occasion, Jesus turned to poetry – the mystical poetry we find in “The Lord’s Prayer.”

No one would dispute the idea that Jesus has a way with words in his teaching. His teachings are life-giving and deeply profound. Jesus used language in many forms to teach: parables of the mustard seed, the leaven and the pearl, among others; His quintessential short story – The Prodigal Son; and, sayings, as in the Gospel of Thomas, “Those who seek should not stop seeking until they find. . .” and the Beatitudes, “Blessed are the poor in Spirit. . .,”each its own deep well of inspiration and truth. But there is one occasion in the Gospels, I believe, when Jesus offered something very different. It was in response to a request from his apostles, “Lord, teach us how to pray.” On this occasion, Jesus turned to poetry – the mystical poetry we find in “The Lord’s Prayer.”

Why poetry?

When and why do we turn to poetry and the poets? What’s different about poetry? Poetry (like all great art forms) is timeless, drawing from just a few words the essence, the truth of an observation, experience or lesson. Poetry makes the silent, bare forest covered in snow come alive or the red rose of summer, literally bleed off the page, while the crash of the waves nearly burst our eardrums, and our souls ache in concert with the suffering of another. Within a poem, words and sounds speak to and in concert with one another, echoing, circling back upon one another to expand meaning. When the subject is in essence a glimpse into the radical truth of human/divine experience, one turns to poetry, because poetry transcends the words and ideas of which it is composed and enters the world of the mystic.

Speaking mystical truth

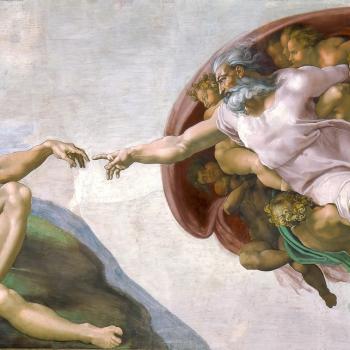

Why was poetry the perfect form for the prayer Jesus planned to teach? Poetry initiates deep connection, shared experience with another, the antithesis of separation. Poetry is appropriate for a prayer outlining separation as the state of being which embodies the single, greatest potential for misalignment – the sin of separation – the failure to remember the most critical truth that we are all part of God’s immanence, that we are all in fact one and that there is nothing which is not God.

When Jesus’ disciples asked Him to teach them how to pray, what were they really asking Him for? A more effective form of intercessory prayer or prayer of praise or prayer of gratitude, perhaps? Or, did they believe that there must be something inherently different about Jesus’ prayer, given who they knew him to be and the faith and healing powers he possessed and brought out in others? They may have believed that He had a “better,” more effective way to pray. They may have wanted a “formula” for prayer, but what they received rather was mystical truth – a mystical truth which when fully realized had the potential to keep them in complete alignment with Source. Jesus had given them a map of the terrain of the journey of life, of incarnation. Jesus gave them in simple language what they needed most – all they would ever really need – a description of full alignment with God and the critical ways in which during incarnation one might fall out of that alignment, become separated from and lose connection with God and all creation.

The Lord’s Prayer

On a recent Sunday at Companions on the Journey, after listening to a homily by Fr. Seán ÓLaoire on “The Lord’s Prayer,” I began to think about the words of the prayer in a way I hadn’t before. The first thing that struck me was that the prayer appeared to begin in heaven and end in hell. There appeared to be a form to the prayer, like that of other forms of poetry, particularly Biblical poetry, in which thoughts within the poem weave in and out, ascend and descend, speaking of or about each other, expanding their meaning. I felt initially that there was a descending order within the prayer, reflecting the necessary densification of Spirit, as one leaves the spiritual realm and enters the world of matter in incarnation.

But, as I thought further about this, I could see that the phrases of what one might think of as opposites (holy/unholy, heaven/hell) were actually parallel within the prayer and could be explored in the following fashion for deeper understanding: honoring God and alignment with God are outlined in the first three statements; ways we fall out of alignment with God are described in the last three; and, incarnation is at the center, the fulcrum, of a V. So there was a descending and, with the entrance of grace, an ascending pattern to the prayer/poem, with the central stage for action, incarnation itself.

The prayer begins by addressing the Father, “Our Father who art in heaven. Hallowed be thy Name.” Hallowed, that is, holy be thy Name. These words are an acknowledgement of the ultimate reality of the love, truth, beauty and goodness of God, and our humility in God’s presence. It is a place of rest for the person praying, as those words (and the holiness they carry) sink into one’s soul. The Our Father ends with the words, “But, deliver us from evil.” This evil is the opposite of holiness. We pray to be delivered from evil, we pray that we may be holy. Evil cannot co-exist with the good. We pray to hold onto our alignment with the ultimate reality of God’s goodness, and to not be separated from that goodness.

In the second phrase, “Thy Kingdom come,” we think of God’s kingdom as heaven. We are instructed in the Gospel of Thomas, 113, to look for the kingdom here and now,

Jesus’ disciples said to him, “When will the kingdom come?” Jesus said, “It will not come by waiting for it. It will not be a matter of saying ‘Here it is’ or ‘There it is’. Rather, the kingdom of the father is spread out upon the earth, and people do not see it.”

The question becomes, how do we learn to see it? Again, we can look to Thomas, 3, for the “here and now” and for the “how,”

But the kingdom is inside of you. And it is outside of you. “When you become acquainted with yourselves, then you will be recognized. And you will understand that it is you who are children of the living father. But if you do not become acquainted with yourselves, then you are in poverty, and it is you who are the poverty.”

When examined in conjunction with the second to last phrase of the prayer, “Lead us not into temptation,” we understand that the abiding temptation is to stay asleep, to “not become acquainted with ourselves,” to look outside ourselves for the kingdom and to fail to recognize/to misunderstand who we really are. This choice has the potential to lead us into temptation, out of heaven and into real difficulty, even into “hell,” where lose our alignment with God and a true sense of our eternal Selves.

In the third phrase, “Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” we wonder what God’s will for us actually is. What is God’s will and how do we do it? The answer comes in the third to last phrase, “And forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Thy will, God’s will, is that we engage in forgiveness, because forgiveness returns us to connection and oneness, and eliminates separation. The ability to forgive is at the heart of a spiritually aligned life. Forgiveness is the work of incarnation.

There is a relationship between pride and separation that is due to an unwillingness to forgive. It is not uncommon to think of pride, as the greatest among the seven deadly sins. Pride in one’s accomplishments and those of others can reflect a healthy sense of self-esteem, but pride can also be distorted into conceit, a sense of better than another, and self-righteousness – all markers of an ego-driven way of seeing oneself as separate from others. These qualities all feed into an inability to forgive. We often find ourselves unable to forgive because we feel that someone has taken something away from us, has injured us or our image in the world. I wonder, is pride at the root of our inability to forgive?

At the base of the V, the center of the prayer, is the simple, beautiful phase, “Give us this day our daily bread.” What do these words mean to us? With these simple words, we pray for all that we need: for food, health, loving relationships, spiritual nourishment, etc. And we pray for God’s grace to sustain us. We pray for everything we need to live a good life, to have the courage to choose the good, to be in alignment with God’s will, to create heaven on earth. With the addition of grace in incarnation, the V-shaped prayer begins its ascent – we pray for the grace to be forgiven and learn forgiveness, our primary task. We pray for the grace to not be overwhelmed by temptation –to learn from temptation, but not forget ourselves in the process. We pray for the grace to be delivered from and not be lost in evil, the hell in which we are most distanced from God.

Through The Lord’s Prayer Jesus teaches us that this life, this incarnation is where we learn and grow, where we might go astray and how to keep our eyes set on the alignment, the unity and connection that we intuitively seek. The unity of all things is the ultimate, mystical reality. If we wake up to this, we will never really be lost.