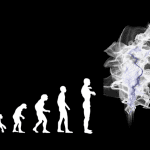

Since the dawn of human history, once consciousness had reached a certain level of abstraction, people were able to stand back from daily concerns and consider the larger nature of existence. How did we get here? Why do events good and bad happen as they do? How much of Nature can be controlled, and what must simply be endured?

Because we gain understanding largely through experience, and most of daily activity involves some sort of purposeful behavior – planning, hunting, gathering, tending, and the like – it was natural to assume that the larger events which are out of our control might also be occurring according to some purpose or design. And this implies some sort of conscious, intentional actor at the controls — perhaps a deity. If this were the case, one would likely want and seek a beneficial relationship with such a power.

The Mortal and the Divine

Life-events divide roughly into two categories — those subject to our own analysis, planning, and control versus those that do not. Because of this, perhaps it was natural for a dualistic view of the cosmos to emerge. On the one hand, a mortal, mundane realm of daily experience. On the other, a mysterious, subtle, transcendental realm, guided by powers we cannot easily fathom. The former could be approached in a practical way through the sciences. For the latter however, we could only approximate through religions and other spiritual/metaphysical philosophies.

Most of the latter philosophies involve particular sets of beliefs and practices that provide mortal adherents with some ability to conceive of and engage with the “higher” realms and entities. One of these is the notion of prayer.

Traditional Notions of Prayer

Prayer is generally thought of as some sort of request, petition, entreaty – or an expression of praise or gratitude – by someone in dependency or of lesser power, to an entity or agency with greater power — one capable of granting or actualizing such requests. Yet, how to conceive of and visualize such a power?

Since it is difficult for the human mind to conceive of anything that has not been part of direct experience — or can be extrapolated from the same (e.g. a human with the strength of an elephant or the ability to fly like a bird), there is a need and tendency to anthropomorphize whatever power is being petitioned. Accordingly, the ancient notions of a god as a mighty, mythical creature or a wise, all-powerful man, sitting somewhere in another realm (the “Heavens”).

Despite several millennia of spiritual thought and practice, an analogy still commonly used for prayer is that of children, entreating a parental figure to alter reality, grant requests and wishes — and sometimes work miracles — in order to effect some desirable change to physical existence — on any scale from personal to global.

Just as small children have little control over the way their lives unfold, the above model of prayer is premised on the belief that the individual has minimal agency over the greater environment in which he or she dwells.

Effecting Change in Reality

Philosopher Alan Watts once suggested that prayer is essentially “telling God how to run the universe”. That is a cynical take, but does raise the question that, if all-wise, all-powerful entities are running the cosmos, is it not a bit presumptuous to take the position “well, in this particular instance, I’ve got a better idea”?

Perhaps because of this, more contemporary spiritual philosophies sometimes avoid the specifics of ‘asks’ and ‘answers’, instead lobbying more generally for “the highest good” or “most benevolent outcome”.

Yet either of the above is premised on a view of the universe somewhat like a machine, designed by a universal clock-maker; one that is now running inexorably by a predetermined design. Through prayer then, one bothers the Clockmaker until they modify some part of the mechanism to run in a different direction.

All of the above denies any human agency in the way our greater world of experience unfolds.

Contemporary Science and the Cosmos

In the “modern” world of today, many consider the above notions to be a primitive, even childish view of the universe, instead holding the position that unfolding scientific understanding will eventually explain and account for all aspects of existence.

Classical science, up through the era of Isaac Newton, held that the universe was essentially a clockwork mechanism. The belief was that once we had discovered all of the “parts” and their trajectories, the workings of the cosmos would be fully understood — and the past or future could be calculated with precision. (This was wonderfully illustrated as the premise of Alex Garland’s 2020 SciFi drama “Devs”.)

However, if you are aware even of the popular accounts of modern physics, you have likely heard of the many paradoxes and irrationalities that show up in physics at the quantum scale: particles that cannot be specifically located and measured, that appear here then there without travel, that communicate instantly over vast distances, that even alter the past (see: Delayed-choice Quantum Eraser experiment).

<<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delayed-choice_quantum_eraser>>

One of the incredible but well established findings of Quantum Mechanics is that quantum-scale objects and events do not exist in a fixed, definite state until actively observed by a conscious observer. Prior to that, they exist only as probabilities.

At the macro-scale — rocks, trees, animals and insects, you and me — all exist as an astronomically large conglomeration of quantum events. Yet we have a stable, functional world because the collective statistical probability of these massive numbers of events becomes predictable enough that if you leave your car keys on the kitchen table in the evening, there is a reasonable probability that you’ll find them there the next morning.

A Quantum Version of “Miracle”

At the macro-scale of daily life, we constantly affect the probabilities of collective quantum events through everything we do. Eating, sleeping, moving, planning, creating, growing, traveling — every thought and activity involves changing the state of vast numbers of quantum events.

Yet as indicated above, every event and phenomenon we engage with is itself composed of vast assemblages of smaller events — down to the level of atoms and molecules, and the fields of which they are comprised.

Some of these assemblages we can affect with our thoughts and actions. For example, we can chop a tree. We can convert the logs to lumber. We can build a house from that lumber. At a bit deeper level, we can plant the seed that grows into the tree. Geneticists might even discover means to modify that seed in various ways to affect its metabolism and result.

However the above is approximately the limit of our current ability to control the assemblages that produce the reality we experience. The finer deep processes that eventually produced the seed from the primordial Big Bang were left to Nature — whether conceived of as a vast, fortunate sequence of random events or the deliberate intent of a creative designer.

Accordingly, any ability to alter aggregations of quantum events at this scale, by deliberate intention, would have to be considered miraculous — and is that not the essence of “prayer”?

The Co-creative Power of Attention

Whether human or divine, what role might consciousness play in the unfolding of reality as we experience it? While classical physicists might say ‘none’, many of the founders of Quantum Mechanics commonly held a different view.

“I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.” — Max Planck

“Not once in the dim past, but continuously, by conscious mind, is the miracle of creation wrought.”

— Sir Arthur Eddington

More recently, several Books have explored at length the role of conscious observation in our experience of reality. In “The Case Against Reality – How Evolution Hid the Truth From Our Eyes”, physicist Donald Hoffman cites many instances where human perception differs from underlying physical conditions — yet in a functional way. His essential point is that we creatures evolved to see things in a way that furthers survival as opposed to revealing objective truth … and sometimes the two do not match up.

In “The Grand Biocentric Design” (and several prior books), physician and researcher Robert Lanza makes the case that the hundreds of universal parameters that are fine-tuned in such a way to support life, are so because that version of the cosmos was observed into existence by life itself.

Each of the above books are based on the premise that consciousness, rather than energy and matter, is the most fundamental factor in the reality that we experience.

If this is so, how might this work? And what does it mean in terms of individual, subjective consciousness versus a more collective or universal consciousness? Might it offer any new insight into the nature of prayer?

This will be explored in the subsequent article “What is the True Nature of Prayer? – Part II”.