It’s amazing what a person can see in a day living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Last month at an education conference in Hillsborough, I listened to a young Harvard post-doc deliver a presentation called “The Confluence of Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science: Deep Learning in the Brain and Mind” and I learned about all the layers of neural networks a visual image is filtered through on its way to becoming a recognizable phenomenon in a person’s mind, just as it can become a recognizable piece of sense-data in a machine’s “mind.” On the same day in the civic center of San Francisco I skated by a shirtless fellow sitting on the sidewalk staring transfixed into the distance. He had one hand on the ground to prop himself and the other one on his head holding what I thought was a pen—he looked like a poet in a swoon. Upon closer inspection, I realized he was holding a hypodermic needle with just a bit of the tell-tale brown color of heroin still in the barrel. I thought about him for a while, thought about the reality that his brain, his actual neural structure, is probably so compromised by that level of drug use that he will never be married, never have a family, never hold a meaningful job again. The forces that allowed one of these people to become a successful researcher in a cutting-edge field and the other to become a street-bound drug addict certainly have a personal dimension, but they have social, political, and spiritual dimensions as well.

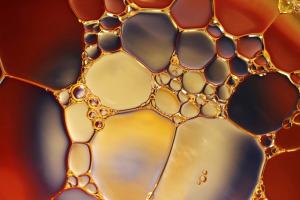

The title of this series is “Politics and Religion: Oil and Water?” with a question mark. As you likely know, under normal circumstances oil and water don’t mix, the oil separating from and floating above the water. So we use the analogy to explore the relationship between politics and religion, which is considerably more complex than two species of molecules retiring to their preferred locations. This series is not simply about “church and politics.” Each of those two entities contains so many elements and so many perspectives that it would be useless to try to tackle the relationship, number one because it would take more than a few posts to tackle, and number two because the crises the world faces—crises that extend beyond the borders of this country and the rosters of churchgoers—are severe enough that the thinking surrounding politics and religion must go far and cut deep. The crises I have in mind include, but are not limited to, the deterioration of livable conditions for all species on Earth, the threat of nuclear war, human overpopulation, global refugee crises, and the yet-to-be-settled question of what the purpose of self-conscious life in the universe is.

Politics is the organization of human community, which includes group decision-making, who exercises authority, and how resources are accessed. Politics entails questions like, “Should government make decisions according to the greatest good for the greatest number, or does government have a responsibility to minority opinions and needs as well?” Or, “should government honor rights of individuals, if the defense of said rights leads to unfair or unjust circumstances for others?” But our focus here includes another aspect of human life at least as old and certainly as deeply woven into civilization—religion.

What we mean by “religion”? Now this is a challenging reality to define. It’s easy to hear, for example, the word “Church” and mentally default to an image of several dozen bishops in Rome discussing moral teaching or the language of the Mass, as if “Church” or “religion” is something institutional like Congress. This would be a narrow conception of religion. Here are some additional images of “religion” that might occur to you:

- a woman puts out her hands to receive the communion wafer and makes the Sign of the Cross after consuming it;

- a man closes his eyes and recites, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God”;

- a man grocery shops in the kosher food aisle to ensure he eats in conformity with Jewish dietary laws;

- a woman carefully dons a hijab before she meets her friends to run errands;

- a man purchases a train ticket to Varánasi, India to celebrate Kumbh Mela with a pilgrimage to the River Ganges.

But religion can also mean more than profession of faith, sacred ritual, or traditional custom. Consider:

- the image of a African-American family in the 1850s trekking across an expanse of snow-covered fields, toes numb, while singing, “Swing low, sweet chariot, coming to carry me home. I looked over Jordan, and what did I see? I saw a band of angels coming after me”—a well-known spiritual likely from the days of the Underground Railroad, with obvious references to the Biblical Promised Land and the assumption into heaven of the prophet Elijah, by chariot;

- the image of St. Joseph’s Catholic House of Hospitality opening in Rochester, New York in 1941 to provide food, clothing, and shelter to every visiting person it can;

- the image of Catholic Sr. Dorothy Stang, who for decades advocated for the rights of the rural poor and the natural environment in Brazil before being murdered for what they perceived as her obstructionism to industry.

So, when we consider the relationship between politics and religion, we’re talking about concepts that manifest in so many different ways that it’s difficult to enumerate all the points of interplay. Perhaps we’d do better to consider the foundation of them both, which is called “world view,” taken from the German word Weltanschauung, which means one’s fundamental perception of the world and orientation within it.

When I teach religious studies classes, we straightaway have to establish that human language is composed of numerous types of statements that serve very different functions. When you’re in middle school, you learn about the differences among declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory statements. Also, you likely learned about what distinguishes facts from opinions, or perhaps more obscure expressions like morals or promises. One concept that the students and I explore is whether there are statements that might be true but that are not provable. Thinking as a scientist or a materialist, we might say that we only take as true what can be proved either empirically or through logic, but it’s important to note that every system of thought rests on certain axioms that are not provable within the internal logic of the system. Kurt Gödel wrote about this notion in mathematics as “the incompleteness theorem.” Consider that in arithmetic, there is no proof that numbers exist or that numbers always come in an order: 1, 2, 3 but not 2, 3, 1. These are unprovable “givens.” We all, every day, operate by unprovable givens. A person who calls himself an atheist, with a purely scientific world view, often still appeals to unprovable truths. For example, the truth that “all persons have dignity and certain inalienable rights” cannot be proven but is a truth taken as given. For many people in Western religious traditions, we see the world as fundamentally good—a truth that isn’t easily relegated to the arena of mere passing opinion, but that is also not provable the way a fact is. Some truths seem good and reasonable, but can pose unintended problems; for example, the “truth” that all persons are created equal. From that axiom, it’s easy to assume that people are responsible for pulling themselves up out of whatever circumstances in which they find themselves, when in reality many people need—more than mere equality—equity, which provides them a reasonable shot at achieving in society from a position of disadvantage. So how then do we define “truth” in this regard? I would say a “truth” is an unprovable conviction that becomes real through our actions. It cannot be proved because it cannot be found in the world—you don’t find human rights or a sense of dignity under a microscope; rather, truths, in the sense I mean, are introduced into the world by us, maybe in the same way that you don’t prove that music exists; rather, you play an instrument, and through your action, the music manifests in the world.