We’re blogging through St. Thomas Aquinas’ Compendium Theologiae, sometimes called his Shorter Summa. Find the previous posts here.

Having established that God must be unchanging by reducing the notion of a changing First Mover to absurdity, Thomas then goes on to make a direct argument for the Unmoved Mover:

Having established that God must be unchanging by reducing the notion of a changing First Mover to absurdity, Thomas then goes on to make a direct argument for the Unmoved Mover:

Among things that are moved and that also move, the following may also be considered. All motion is observed to proceed from something immobile, that is, from something that is not moved according to the particular species of motion in question.

This is another principle from Aristotle’s Physics, and I’m afraid I won’t be able to do it complete justice. But suppose I throw a ball: the ball goes flying, but I remain. Or consider a dog, walking: the dog is moving forward, but at any given point in time one or two of the dogs paws are in contact with the ground and are more or less stationary, pushing the dog forward.

This example of the walking dog is particularly important, because it shows that the thing that is unmoving need not be an external thing; the dog is moving in one respect and stationary in another respect.

These examples involve local motion, movement from place to place, but Thomas takes it as a general principle; I assume he is following Aristotle in this:

Thus we see that alterations and generations and corruptions occurring in lower bodies are reduced, as to their first mover, to a heavenly body that is not moved according to this species of motion, since it is incapable of being generated, and is incorruptible and unalterable. Therefore the first principle of all motion must be absolutely immobile.

This is both an illustration and an argument. For Aristotle, change here on Earth derives from the First Mover, but not directly; rather, the First Mover moves the heavenly bodies, and the influence of the heavenly bodies moves things here on Earth. As I noted in a previous chapter, these heavenly bodies are presumed to be perfect, unchanging spheres, moving in the sky but changing in no other way. This architecture of reality strikes we moderns as absurd; but as I’ve noted before the heavenly bodies aren’t an essential part of Thomas’ system.

The point is that as physical motion is driven by something stationary, so a thing’s coming to be and passing way must ultimately be driven by something that does neither, and all other kinds of change must flow from something unchanging.

I’ve not read the arguments for the principle itself, so I can’t really defend it; but the presence of the heavenly bodies in the argument are, as usual, an illustration. Don’t get hung up on them.

____

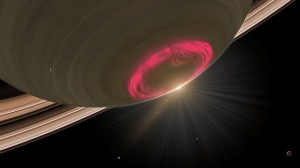

photo credit: NASA Goddard Photo and Video via photopin cc