The Spanish artist Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) is a contradiction. His disarming virtuosity, combined with an ambivalent attitude toward painting that borders on contempt, resulted in one of the most stunning and enigmatic careers of any artist in the Western tradition. He also produced some of the most graceful paintings in the history of art.

Velázquez’s genius was obvious to his peers, who were jealous and resentful, and who responded by criticizing him for being merely a painter of portraits (private commissions) rather than of religious and history paintings (public commissions). Velázquez treated his jealous peers by painting portraits with such vicious virtuosity that they appear to be dashed off as a second-thought. The fact that Velázquez seemed to have used the canvases he was painted on to clean his brushes, a supreme act of artistic gusto, disregard for his craft, and even disdain for his patron/subject, only deepens our sense that this is an artist of unprecedented genius and colossal disinterest.

Painting came easier for Velázquez than any master in the Western tradition. Rembrandt, Matisse, Picasso, and even Raphael, seem somewhat plodding and workmanlike in comparison to the Spaniard’s effortless gestures. No artist seems to have cared less about his craft than Velázquez, who apparently suffered none of the angst, paranoia, desperation, and hang-ups that plagues yet also drives nearly every artist, including his contemporaries, who were enraged by his ambivalence, enraged by how easily he painted, how easily he won over patrons, and how unimpressed he seemed to be by his achievements. Velázquez also only painted unless he was asked to do so by his friend and king. And he stubbornly refused to paint history and religious pictures, the genre that had attracted the masters for centuries, featuring the heroes and heroic acts of classical mythology and the Judeo-Christian tradition and could truly showcase his greatness through the glory of his subjects. What seemed to interest him, however, were the people he knew, observed, respected, and loved. How could one so gifted care so little about his gift?

Velázquez’s extraordinary talent put him in a position not to have to care about painting, possessing one of the great official posts of any painter in the Western tradition, court painter for his friend King Phillip IV. Velázquez seemed happiest when he wasn’t painting, serving his friend as an ambassador or traveling throughout Italy acquiring a massive collection of Renaissance masterpieces that would form the core of the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Apparently, the king had to make up excuses—painting commissions—to bring his friend back to court. Although Velázquez was clearly passionate about curating the court collection, of recognizing artistic greatness in others, his great loves were God and his wife, to whom he was deeply faithful—and the Order of Santiago, an exclusive religious society for which he seemed to care enough about to lobby for it.

Velázquez’s career exuded grace. And this grace infuriated his rivals. His paintings breathe easily, with confident brush strokes, displaying a lack of fuss and obsession and giving his works a spontaneity and freshness that makes every picture appear almost comical, that is, a part of the comic vision that takes imperfect, broken humanity and breaths life into it, in spite of itself. The ease with which Velázquez worked defies effort, contradicts the blood, sweat, and tears that characterize work under the sun, this side of the kingdom.

The freedom, the breadth, and space that his paintings create among his subjects, are also the products of an artist who is not defined by his paintings, who makes pictures gratuitously, graciously, not because he has to, because he has some internal psychic drive that demands he produce painting after painting, like the biological demands of a digestive system. Velázquez is remarkably free, it seems, not to make paintings. And so the ones that he does produce seem a surprise. The gifts that Velázquez received from God seem most gift-like when they are not employed, or employed out of freedom, not from demand or necessity. He seemed to have preserved God’s gifts as grace, as gospel, not transforming them into law, into a means by which Velázquez achieved his own recognition.

Velázquez’s paintings come into existence from a state of grace, which Leonard Cohen once described as

that kind of balance with which you ride the chaos that you find around you. It’s not a matter of resolving the chaos as there is something arrogant and war-like about putting the world in order but having that kind of an escape ski, down over a hill, just going through the contours of the hill” (Ladies and Gentleman…Leonard Cohen, 1964).

Velázquez’s pictures skirt the chaos and sketch the contours. They blatantly, violently contradict the anxiety that plagues the world of art, the world of aesthetic justification. Velásquez’s work seems the perfect example of the Dutch Reformed art historian H.R. Rookmaaker’s well known statement, “art needs no justification.”

But what kind of artist would clean his brush on the canvas he was working on or appear disinterested in his genius? An artist whose greatest paintings are of dwarfs and dogs.

Art historians and theorists claim that Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656) is one of the first modern paintings. This is most certainly true and it is one of the pictures I have used in the classroom to articulate the development of modernism. Yet what is most remarkable is the German Shepherd in the lower right hand corner and the dwarf that stands behind it. They are two gratuitous elements in a painting that is about the artist, the king and his daughter. Yet the dog and the dwarf seize our attention—the dog is one of the most magnificent animals depicted in any painting, capturing its nobility, fidelity, and contentment of a creature clearly adored by the entourage, unfazed even by a bit of heckling. The dwarf is also represented with dignity, as she is the only one of the group that notices and addresses the viewer. Neither the dog nor the dwarf operate in important, “meaningful” ways in the interpretation of the painting, which is a religious painting, disguised as a self-portrait, disguised as a group portrait of the royal family, disguised as a portrait of the royal child. And yet.

And yet their presence, painted with such bravura, are an intrusion, an aesthetic disruption. The world does not work according to what is obvious—wealth, power, prestige, and the rat race of ambition and aspiration, disclosed by the artist himself, the royal couple, and their child. It operates through weakness, through the creature, at the level of the pet and fool.

Detail, Las Meninas, oil on canvas, 1656

Dwarfs played an important yet varied role in court life. They offered amusement and distraction. They were recipients of the court’s benevolence, and perhaps even served to affirm the benefactor’s perfection, nobility, and superiority. However, there is a tradition in art and literature, most notably with the fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear, in which the fool becomes instrumental in Lear’s transformation. Velázquez painted a number of dwarfs, and although he was not the first artist to do so (the Italian Bronzino’s dwarfs come to mind), he is distinctive in how he depicts them.

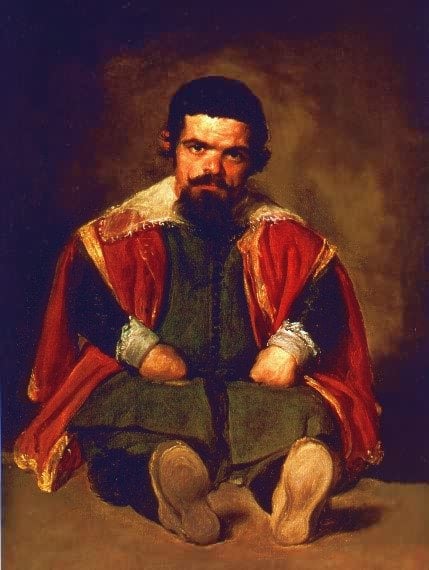

The Dwarf Sebastian de Morra, 1645, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Velázquez painted many dwarfs, depicting them with considerable dignity. They are portraits—that is, they affirm the integrity of the subject as an individual, worthy of a name, a psychological investigation, a portrait. And no doubt Velázquez treats them as bearing God’s image, revealing them to be as intelligent, wise, and as experienced as any person in the court. And yet.

And yet it is difficult to ignore that something else is happening. Because Velázquez has such light regard for painting, it is possible to look at these dignified and insightful portraits of dwarfs as representative of the human condition, stripped of its pretense of beauty, honor, strength, wealth. Rather than lifting the dwarfs up, perhaps he is bringing the wealthy, the powerful, and the beautiful down. The dwarf discloses the human condition more honestly and directly than kings, dukes, and ambassadors. And this is also evidenced in many of his portraits of his friend and king, Phillip IV, who exhibits a vulnerability, discomfort, and naiveté that is in stark contrast to the determined confidence of the dwarf Sebastian de Morra. Perhaps Velázquez, with his penchant for dwarfs, is representing the profound imperfections of humanity, which he experienced in daily court life, through a God-given gift that he himself could not take seriously, refusing to cling to as constitutive of his identity?

Grace is an intrusion, a contradiction, and, as it relates to the legal scheme that drives the world, a threat. And no doubt Velázquez’s talent and lack of artistic ambition was perceived that way among his contemporaries. The breeze that blows through his paintings, overwhelms the tension and anxiety of the Spanish court, transforming it into a carnival freak show, a comic representation of the human condition so wounded, distorted, and blemished, that only God’s grace could bring them to life. These remarkable grace-filled paintings, so loose, so free, so confident, bring his subjects to life.

Detail, The Needlewoman, oil on canvas, c. 1640/50, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Is it possible that Velázquez was all too aware that his genius as a painter was a gracious gift of God and thus something not to be grasped, clung to, transformed into a means of self-justification? The means of grace that blows through the court, that enlivens and gives space, allowing us to take a deep breath, as Lutheran theologian Oswald Bayer would say, penetrates the dwarfs, the royalty, the dogs, and every brushstroke of every portrait, an artistic foretaste of God’s promise to make all old, crippled, and insecure things new.