God calls an artist to be a particular kind of artist in a particular kind of way in the world. This specificity reveals the diversity of artistic practice and the various ways that it is embodied institutionally. Most Christian thinking about art, however, ignores this basic social reality, which every artist (Christian or not) confronts daily. Theological reflection on art begins with the felt reality of the studio, addressing the technical and vocational decisions that confront the artist.

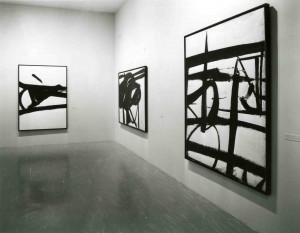

Whether an artist realizes it or not, every technical decision she makes in her studio proves what kind of artist she is and will be in the world, what kind of witness she will be to art. A work of art is much more and other than a confessional record of the artist’s feelings or emotions, or the result of her so-called “creativity” and “innovation” (both words I find unhelpful). A work of art is an event which unveils a world, and in the process makes a claim on its audience to believe it. Made in and through the artist’s irreducible individuality, hewn through her experience in and of the world, and wrought in the most private of spaces (her studio), the work of art discloses a world for the world when it leaves the studio. Yet a work of art is not offered to the “world” in the abstract or in general. It is offered to a viewer, one who stands in front of it, allows herself to be confronted by it. It is offered to me. At that particular moment when I come upon this painting in a gallery or a museum, I am the “world” to whom the artist is offering her world, as it unfolds toward me and my world.

Yet the artist does not know me, does not know the me or the you who will be confronted by the work. In a provocative essay, entitled “To the Addressee,” the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam claimed that writing a poem is like putting a message in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean. Whoever comes across the bottle and reads the message, is the addressee, the intended reader. It is written to and for him. Mandelstam suggests that the poem creates its reader, or, perhaps even more suggestively from a theological perspective, elects its reader, actualizing, or bringing to be its audience one person at a time, across time.

This is not how we, as evangelicals, like to think about art, and, in fact, like to regard anything related to culture, for that matter. We are the ones impatiently in control. I am the one that sees a work of art; I am the one that “interprets” it, vetting its appropriateness according to a list of my own criteria, certainly not drawn from the history and tradition of art that exists outside of me. I am the one that judges a work of art and its “appropriateness.” I am active and the work of art is passive. I am the subject and the work of art hanging there on the wall of the museum or gallery is the object of my efforts, my work, my actions. The work awaits my justification and my use. And that justification and use has most likely to do with cultural politics, with winning the culture wars, staving off the encroachments of secularism, postmodernism, or whatever bogeyman “ism” is deemed a threat to “Christian values.”

But that is simply not how art behaves. From an aesthetic point of view, we are passive. The history of criticism is the history of reflection on the relationship—the struggle—between a work of art that exerts itself on the viewer, reader, listener through time, through generations of viewers, readers, listeners. The history of criticism is overflowing with works of art that received condemnation from its contemporaries, but which are now undisputed masterpieces (Melville’s Moby-Dick is but one of the most glaring). This history is also full of works praised by their audience, which are now forgotten or dismissed as irrelevant at worst, “period pieces” at best. The force that the critic exerts on the work is mitigated by his posture of receptivity, even with work the critic ultimately distrusts, or condemns, or finds problematic. His aggression is a response to the activity of the work of art that imposes itself on the critic because he allows it.

We do not exercise our freedom when we experience a work of art. We are forced to acknowledge the brut fact and infuriating reality that we are not free. We have been chosen by that painting. We receive or reject it only in response. This is a crucial aspect of experiencing art that is ignored by evangelicals in our rush to “engage” or “transform” culture, and “read” images alongside the morning paper. We want to to apply our “Christian world view,” amounting to little more than list of social conventions, to cultural practices like art, which ask a different approach: a posture of receptivity, humility, and trust that proceeds from the dangerous love of one’s neighbor, whether that neighbor is our enemy or a painting.

When I turn the corner in the museum or gallery, and, being discovered by a painting, agree to open that message in a bottle, it asks a simple question, “How will you respond to me?”

That is a question that we evangelicals, in our rush to transform, engage, condemn, or otherwise “use” culture for our own purposes, rarely answer because we rarely hear it. And by refusing to sit still and listen to what art says, experience the world that the artist offers us as a gift, our witness to Christ in culture, our “faithful presence,” is already compromised.