One of the most enjoyable aspects of teaching art history to college students is presenting to them an artist or work of art with which they have been long familiar, perhaps Michelangelo and his famous Pietà or Marcel Duchamp and his infamous Fountain, and opening it up to reveal something they hadn’t noticed, taking it out of their familiar categories and re-enchanting it.

So from time to time I will try to do the same here. And if there are works of art you’d like me to address, please suggest them in the comments section.

Our first profile is the French Impressionist Claude Monet (1840-1926).

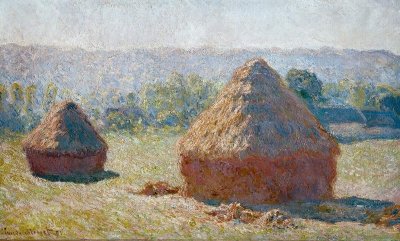

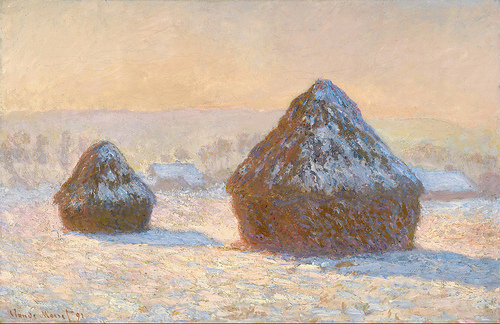

We love Monet’s paintings: charming scenes of nineteenth century Parisian life, sun-drenched depictions of picnics, regattas, weekend walks, sunsets and sunrises, and those adorable haystacks. We delight in the messy and bright-colored brushstrokes that suddenly come together in a delightful image. Reproductions of these paintings adorn greeting cards, decorate walls of waiting rooms, and fill college dorm rooms. And thousands flock to museums to see the paintings themselves. This was not the case in Monet’s day. He was derided by critics as an “impressionist,” who had the gall to exhibit his barely legible paint-smeared sketches as finished paintings. And one critic claimed that these paintings looked like Monet simply threw paint on the canvas.

Monet revolutionized landscape painting by killing it. Its traditional function was to serve as a backdrop for historical and religious narratives. The artist would travel to Italy and fill a notebook with drawings of trees, hills, and other geographical features, which he would spend the rest of his career incorporating into his landscape paintings. With their “Italianate” flora and fauna, these paintings evoked a timeless golden age. Monet, on the other hand, took his easel out into the Parisian countryside and painted what he saw.

Rather than serve as stage sets for heroic narratives from classical literature or the Bible, Monet’s landscapes celebrated the everyday experience of nineteenth century bourgeois Parisian life. He was excoriated by critics and colleagues because his subjects were not worthy of Art, the goal of which was to represent the timeless essence of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful.

A painting was supposed to stand outside of time. The sun always shone at high noon, which, by minimizing shadows, provided the most “rational” and “timeless” expression of virtue in paint.

In contrast, when Monet left the controlled environs of his studio and dragged his canvases and paints into the countryside, he went to battle with the shadows, with the temporal, the ephemeral, transitory, and local. Monet, not Thomas Kinkade, is the painter of light. Whether a bouquet of flowers, a couple enjoying a picnic, or a haystack, Monet was concerned with depicting his subject as constituted by light—but that light was ever changing.

Monet painted dozens and dozens of haystacks in 1891. He was fascinated by their change in appearance at different times of the day and at different times throughout the year. These seemingly charming paintings of a rural French countryside are in reality knock-down-drag-out bare-knuckled fistfights with light. And they are battles that Monet always lost. To paint the play of light on haystacks in the morning or at dusk is to paint a subject that never stood still. Every painting of the haystacks is a painting of a subject that disappeared right before his eyes. The quick brushstrokes that we see on these canvases is evidence of Monet’s urgency, his desperation to beat the clock.

Each painting of these haystacks, then, is a failure, for it it incapable ultimately of “capturing,” of rendering its subject in its essence. Painting can only offer a glimpse, a fragment, a part of the haystack as it emergences and ultimately disappears through time. Rather than depict triumphantly the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, Monet’s humble haystacks (like all of his canvases), celebrate their own weakness, failure, and inability to grasp the magic of the natural world, the glow of our experiences of the world, which are always tempered by our realization that this moment will never return. Monet’s intention was to exhibit all of his haystack paintings together, as a single expression of his failure to capture the haystack, to freeze time. For the first time in the western tradition, painting was defined by what it couldn’t do, by its weakness.

To stand in front of a painting by Monet is to be reminded that even through death, loss, and brokenness the world still crackles with the electricity of wonder and astonishment. It is to be reminded that even as it all passes away, and death awaits, that that painting of a haystack, that little failure in paint, is a good gift to us, and in a million different ways we receive it and understand it as such.

And so it seems that even in their weakness and failure—in the limp that these paintings bear after their struggle with light and time—they nevertheless endure, persist, and persevere. They even seem to whisper defiantly, “Not so.” This is not the end.

These paintings of haystacks (and perhaps all great painting) bear witness to the hope that if all is passing away, perhaps brokenness and death will as well.