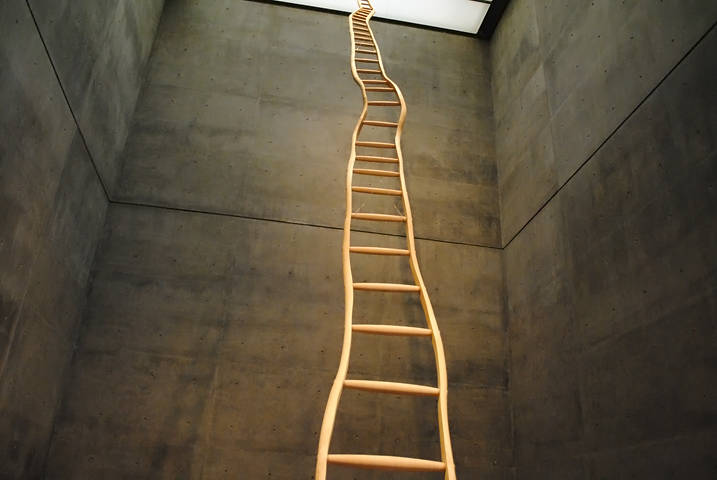

There is a habit of thinking among Christian artists, philosophers, and theologians that conceives of the work of art as a ladder. It uplifts, drawing one closer to God. It is believed to do this in two ways.

First, it operates in the register of philosophy, participating in the timeless ideas and eternal forms of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. It is a means by which thinking Christians re-invest art with seriousness and significance through the abstract categories of theological aesthetics or worldview.

Second, it encompasses a mystical perspective. Following the tradition of John Climacus (St. John of the Ladder) and Meister Eckert, art is a means by which the artist climbs the ladder of divine devotional ascent. The work of art becomes an aesthetic extension of this inward and upward quest. It is a means by which feeling Christians re-invest art with spiritual significance, demonstrating its necessity for spiritual growth, revealing its liturgical relevance for the church, and arguing for the important role that artists as spiritual creatives play in the church.

The ladder generates a lot of talk in the seminar room about what art (in the abstract) is supposed to be doing theologically and philosophically as well as a lot of talk from artists about the exalted role that art plays in their private spiritual lives. But this image of the ladder and its language of ascent isolate the work of art from the viewer, depriving it of its material integrity in the gallery space, and the power of how the work of art is received.

In both the philosophical and devotional approaches to art, the viewer is left behind as the artist climbs the ladder with her painting. The ladder allows the artist (and the theologian) to move quickly into the rarified air of philosophical and mystical abstractions, leaving the particular work of art—its making as well as its reception—virtually untouched theologically. Yet it is there, in the concrete specificity of the work of art and the relationships that it generates— its coming to be in the studio and its encounter with a viewer in the gallery—that significant, perhaps even unprecedented potential for theological reflection can be found.

But to get at it, we need to put aside the image of the ladder and renew our acquaintance with a fundamental Reformation insight—the distinction between our vertical relationship to God through faith and our horizontal relationship to the world through love. Our posture before the face of God (coram Deo) is a passive one—we receive the faith that the Word creates. Our relationship to the world (coram mundo), as a result, is freed to be active. Justified by God in Christ through faith (vertically), we are liberated to love the world, care and cultivate the creation and love our neighbor (horizontally). Through faith we receive the world as a gift.

For Luther, then, there is no ascent. The ladder is God’s to use, not ours. And as Gerhard Forde has argued, the “fall” was really a “falling upward,” consisting in Adam and Eve’s divine ascent as they lost contact with the world, forgetting their contingency as creatures. A work of art, then, does not lift us up as much as it plants our feet firmly on the ground. Through the gritty materiality of paint, graphite, paper, canvas, and wood, a work of art opens our eyes to the world around us. Art is not a ladder. But, perhaps it is a bridge.

The metaphor of the bridge activates and privileges the horizontal relationship of love, putting artistic practice in the earthy (and ethical) context of loving your neighbor. The work of art, then, is a gift to another, recovering the distinctive and theologically rich relationship between the work of art and the viewer.

For Luther, it was this horizontal relationship of love, disentangled from the burden of participating or proving our justification coram Deo that was the impetus behind his revolutionary doctrine of vocation, which was, in many ways, merely the result of his understanding of justification. It was through our work, and the exercise of our talents and expertise, that we love our neighbor. And it is through this work that God is hidden but busy in the world. Our vocation, whether it consists of making shoes or paintings, exists for our neighbor.

This image returns art to the public sphere, to the community of seers, hearers, and feelers. The mystery of the work of art is that it is indeed made for us (even when the artist does not have an idea of who “we” are). And when it encounters us, even centuries later, it singles me out.

The bridge also acknowledges that as human beings we are cut off from one another, and the work of art, as a gift, spans this existential divide. Rather than a ladder that the artist climbs, leaving the world behind, the work of art connects one human being to another through the material of creation modeled, smeared, and shaped into an artifact. Yet what a work of art connects is not only the personhood of the artist and the viewer, but the human in general. The universality of the human experience, of the human condition, is disclosed by this particular painting, made by this particular artist, confronting that particular viewer. A product of the particular artist’s agency, the painting nevertheless transcends this particular agency, cannot be contained by it.

A painting of sunflowers by Van Gogh does not only make the artist himself present to me, but also makes humanity present to me, returns my humanity to me as a blessing, not as an instrument, obstacle, or curse. A painting opens our eyes and ears to the world, awakening our humanity, as creatures, which is returned to us as a gift from our creator.

The image of the bridge does not de-emphasize the sacramentality of the mystical presence of God in the world. It merely reaffirms that it is God who comes to us, in Word and Sacrament through his right-hand work in the church and in paint and canvas (among many other means) through his left-hand work in the world through vocation. Both hands of God are busy at work in the world and he is, as Paul writes, “actually not far from each one of us” (Acts 17: 27). The bridge, therefore, testifies to God’s radical and disruptive grace, for God is here with us, not “up there” somewhere or buried in our hearts. As Heinrich Bornkamm writes,”Grace is the bridge thrown by God across the abyss that separates us from him.”

Both the ladder and the bridge are God’s, to which he graciously comes to us, freeing us to come to our neighbor. Through the love of our neighbor, we are the means by which God is present and active in the world.

And he is present and active in the world through such silly and vulnerable things as a painting, a most mysterious yet often overlooked manifestation of love.