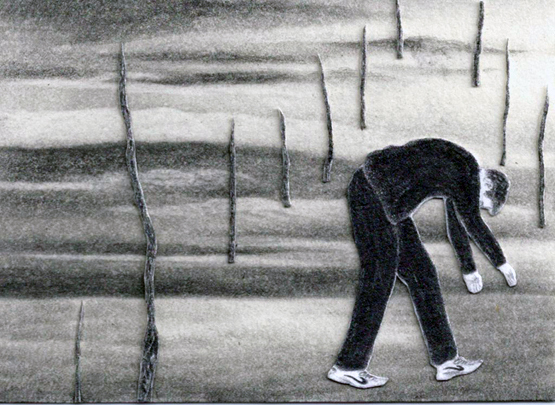

Robyn O’Neil, Hell (2009-2011)

This time of year brings the remembrance of those whom we have lost during the last twelve months. In the aftermath of hurricane Sandy in late October, which flooded the neighborhoods that make up Chelsea on the lower west side of Manhattan and the center of the art world, many artists lost precious works of art, which were located in underground storage or on first floor gallery spaces. The artists (and the dealers) suffered considerable financial loss. But the artists also suffered the loss of works they had labored to bring into the world.

The Abstract Expressionist painter Mark Rothko once said that it is a risky business to send a work of art out into the world, and hurricane Sandy is a reminder of yet another way of understanding the sacrifice an artist makes to bring such a weak and vulnerable thing as a painting into the world.

My friend Robyn O’Neil suffered an immense loss in October. Her complex and labor-intensive drawings were included in the Whitney Biennial in 2004 and her work has been included in numerous museum exhibitions, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago as well as solo museum exhibitions at The Des Moines Art Center and the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, Texas. She is represented by Praz-Delavellade Gallery in Paris and Berlin; Susan Inglett Gallery in New York; and Talley Dunn Gallery in Dallas. An artist of prodigious literary and cinematic interests, O’Neil has turned to film and opera after studying at Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School in Los Angeles. (See the trailer for her film, “We, The Masses.”) And for more information about O’Neil and her work, see the insightful interview in The Believer as well as interviews here and here as well as her website.

When she moved her studio from Houston to Los Angeles in late in 2010, she brought with her a colossal drawing that challenged her physical health and mental endurance as well as her artistic imagination. This drawing was the culmination of her work as an artist, and, to this day, represents a watershed in her development as an artist, perhaps even a Magnum Opus, summing up the first stage of her career.

Detail, Hell

It is a drawing seven-feet high and fourteen-feet long, featuring 65,000 figures and 35,000 collage elements and three parts. It features the awkward and bumbling middle-aged men in sweatsuits and Nike tennis shoes that had become a familiar part of her work as they attempt to escape a vast but sublimely barren, snow-filled landscape. The work was exhibited last October at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York.

O’Neil called it Hell.

The artist at work in her studio near Houston, Texas

It seems likely that the title also refers to the process of bringing this behemoth in graphite into existence. O’Neil is an artist who draws, and draws tightly. She works microscopically on gigantic sheets of paper. Even the smaller works she produces, feel as though they are colossal projects, completed within a hair’s breath of the artist’s life, her last amount of emotional and physical energy spent. Her labor-intensive working process means that her fingers and hand cause her chronic pain. And the very large scale on which she works means that her body must assume awkward and difficult positions for hours. O’Neil’s physical health is compromised by each drawing she makes. Although she is young (35 years old), the effort of making these drawings have taken a significant physical toll. And so it makes all the more remarkable that O’Neil conceived of such a dangerous creature as Hell and was able to complete it over a three-year period.

And all the more tragic that it no longer exists. When O’Neil informed me of the fate of the drawing I experienced a profound sense of loss, for her, of course—it was indeed her loss. But it was not hers alone. It was mine as well. I missed my chance to meet that drawing last year. But I had plans to see it, plans to write about it, plans perhaps even to show it.

O’Neil is one of two artists whose work has shaped my understanding of art and studio practice over the past ten years. I’ve written about her work several times and think about it often. And since late October, a day doesn’t go by that I don’t think about that drawing, a drawing for which O’Neil sacrificed so much. And a drawing I won’t see—a gigantic piece of the artistic puzzle of O’Neil’s life that is lost for me.

In the summer of 2011 O’Neil invited me to the opening of the exhibition in New York. She told me she was working eighteen hours a day and would continue to do so for the next two months in order to complete it. She said she was over her head. She said she was exhausted. And she said that of all the people she knew in the world, I would appreciate what she was doing in that drawing the most.

And I missed it.

Under the very best circumstances, making a work of art is an absurd risk, and by all the standards of the world, a waste of time and effort and so I cannot imagine the void that an artist feels, the black hole that emerges, when a work of art is lost. Yet I cannot deny my own loss. O’Neil’s work exists in my imagination as a series of discrete experiences. But this most important work, this work that cost the artist so much, this work that she wanted me to see, exists for me only in photographs, photographs that haunt me.

This drawing, so prophetically named, will no doubt continue to exist for O’Neil, exerting its presence on her work throughout her life.

As for me, I cannot help but think that there is hope for Hell, that the drawing that almost killed its maker has a future for me, even if it’s only as a gaping hole in my imagination.