Last week, after finishing Alex Danchev’s stunning biography, Cézanne: A Life (Pantheon, 2012), I flew to New York to see some of Cézanne’s paintings at the Museum of Modern Art. This is not exactly the kind of behavior one would expect from an evangelical on staff at a conservative Presbyterian church in South Florida. To make matters worse, I wasn’t going there to gather evidence on the evils of modernism or research the disastrous effect of modern art on the Good, the True, or the Beautiful.

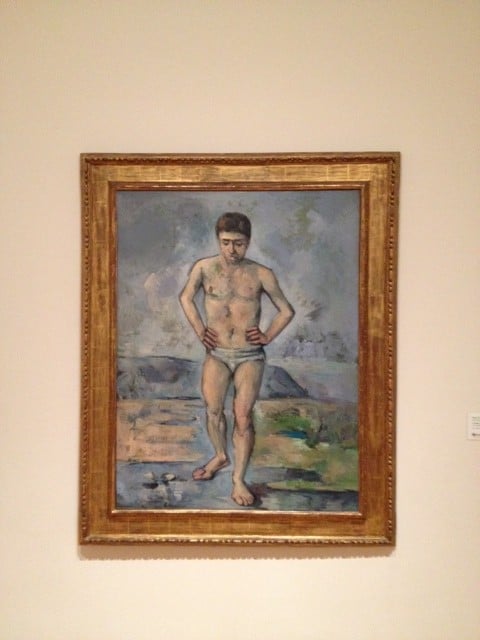

These paintings and I have a history. We first met when I was a graduate student in New York over twenty years ago. I initially considered the clunky landscapes, sloping still lifes, and thick bathers to be nothing but bridges to abstraction, an awkward but necessary transition from Monet to the defiant black squares of Malevich or the tragic gestures of Pollock. If they were important for me, they were so only historically.

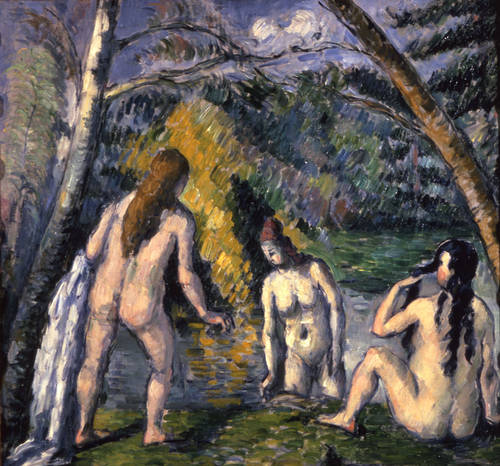

But others, like Monet, Rodin, Rilke, and Heidegger, whom I was devouring at the time, thought otherwise: “If only one could think as directly,” Heidegger said, “as Cézanne paints.” In 1899 Henri Matisse purchased this strange little painting, Three Bathers (1879-82), at great financial sacrifice.

In an interview in 1925 Matisse confessed:

If you only knew the moral strength, the encouragement that his remarkable example gave me all my life! In moments of doubt, when I was searching for myself, frightened sometimes by my discoveries, I thought: “If Cézanne is right, I am right.” And I knew that Cézanne had made no mistake.

Matisse continued, “It has sustained me morally in the critical moments of my venture as an artist…I have drawn from it my faith and perseverance.”

For two years I fought with Cézanne. Going to see the Abstract Expressionists or the latest traveling exhibition at MoMA, I inevitably found myself being stared at by his strange pictures.

What was I missing?

According to Danchev, this was not an unusual question. “For a long time nothing,” Rilke writes, “and suddenly one has the right eyes.”

The “right eyes” did not come for me in graduate school. They came gradually as I began to work closely with artists over the next few years, to sit with them in their studios, watch them work, and reflect on our conversations. It happened as I wrote about paintings, organized exhibitions, and instructed students. And perhaps most importantly, it happened as I experienced the struggle to remain faithful to my vocation, to what took me to New York to study modern art in the first place. It happened in the midst of professional challenges and personal responsibilities, involving much more than paintings, such as my family and my faith.

The “right eyes” came as I suffered as a human being and experienced failure as a husband, father, and art historian. They came as I witnessed similar suffering and failure in the lives of the artists about whom I cared so deeply. The “right eyes” came when I looked at Cézanne’s paintings and saw them as artifacts made by a human being who suffered his vocation, suffered his artistic project, struggling with doubt his entire life.

What was his artistic project?

Cézanne’s lone artistic goal was to paint nature as he experienced it, as he received it, “sur le motif,” as he would say—that is, out in the landscape where he would set up his easel.

The results were surprising, to say the least.

It is not surprising, however, that Cézanne, an introvert who painted himself into a recluse, was desperate for what he himself called “moral support,” clinging to friends to affirm his direction amidst the rejection he experienced and the criticism he received.

Amidst the insecurities and doubt, the resistance and misunderstanding, he painted until the day he died, after having contracted an illness while being caught in a thunderstorm when he was painting sur le motif. He made 954 paintings, 645 watercolors and 1,400 drawings over the span of his lifetime. He rose at 4am and was either in his studio or sur le motif by 7am. Every day.

Danchev’s biography is not merely the story of the most important painter in the history of modernism, but a story of a vocation, the story of becoming an artist against the establishment that never recognized his work. Cézanne created a vocation ex nihilo. As a young man and a bit of a momma’s boy, Cézanne was reluctant to join his best friend Emile Zola in Paris to begin his career as an artist. Zola described the situation to a mutual friend: “Paul may have the genius of a great painter; he will never have the genius to become one.”

He became one.

And he did so by remaining a servant to the world around him, looking and studying and ultimately reveling in the wonder and mystery of what was given. He would sit for hours staring into the landscape with no movement, “lizard-like.” It was claimed that it could be twenty minutes to an hour between brushstrokes. While his establishment colleagues in the Academy painted mythical figures, gods and goddesses, cherubs and putti, “elevating” the imagination of the viewer, Cézanne dwelt in his and our creatureliness, feet firmly planted on the ground. Many of his admirers claimed that his greatest gift was to paint the weight of his subjects, whether it was a head, house, or oak tree. One hostile critic claimed that he could even paint bad breath. Rather than claim to ascend to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, Cézanne, who quoted Virgil and Horace “by the yard,” was content to set up his easel in the secluded countryside and receive the world as it was given to him that day, at that moment.

Cézanne’s art and life is a reminder that we live our lives sur le motif. We are always “in it,” that is, in the terrible beauty, suffering, and terrifying givenness of the world, as our stomach churns and our mind races. Heidegger said that Cézanne’s paintings declare one thing: “life is terrifying.”

And yet, Cézanne’s paintings might say one word more.

Although it is terrifying, full of pain, suffering and doubt, if we allow ourselves to sit still, perhaps lizard-like, and look closely enough, we can receive life as a gift.

What was I doing at MoMA looking at those odd paintings by Cézanne?

I was looking for moral support.