One of the more interesting resources on the Internet is the collected interviews at Paris Review. It is a sixty-year archive of hundreds of long form conversations with poets and writers, like Mary Karr, R Crumb, Billy Collins, Robert Frost, Jack Kerouac, and Czeslaw Milosz, among many, many others.

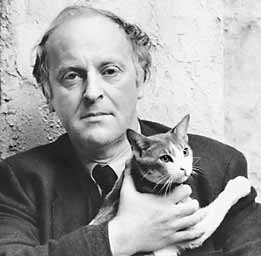

One of the more provocative interviews is with the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, whose critical prose has a significant impact on me, opening up to me the work of Robert Frost, W.H. Auden, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Tomas Venclova. Here’s something from Joseph Brodsky’s 1982 interview that has occupied my thoughts lately.

The thing is that you can always go on, even when you have the most terrific ending. For the poet the credo or doctrine is not the point of arrival but is, on the contrary, the point of departure for the metaphysical journey. For instance, you write a poem about the crucifixion. You have decided to go ten stanzas—and yet it’s the third stanza and you’ve already dealt with the crucifixion. You have to go beyond that and add something—to develop it into something which is not there yet. Basically what I’m saying is that the poetic notion of infinity is far greater, and it’s almost self-propelled by the form. Once in a conversation with Tony Hecht at Breadloaf we were talking about the usage of the Bible, and he said, “Joseph, wouldn’t you agree that what a poet does is to try to make more sense out of these things?” And that’s what it is—there’s more sense, ya? In the works of the better poets you get the sensation that they’re not talking to people anymore, or to some seraphical creature. What they’re doing is simply talking back to the language itself—as beauty, sensuality, wisdom, irony—those aspects of language of which the poet is a clear mirror. Poetry is not an art or a branch of art, it’s something more. If what distinguishes us from other species is speech, then poetry, which is the supreme linguistic operation, is our anthropological, indeed genetic, goal. Anyone who regards poetry as an entertainment, as a “read,” commits an anthropological crime, in the first place, against himself.

If God speaks and does so through promises (“I am the Lord your God,” “Be opened!” “I will be with you even unto the end of the age”), he has, however, entrusted these promises, divine speech acts that do what they say, to be communicated “from creature to creature,” as Kant’s friend and chief critic Johann Georg Hamann once said. Moreover, creation itself speaks, pouring forth speech daily (Ps 19). In fact, theologian Oswald Bayer has even called creation itself a “speech act,” one that can only be received as a promise.

What is a poet doing when, as Brodsky observes, he is “simply talking back to the language itself?”

What does the poet hear?

And how are we to understand poetry in relation to divine speech, since, in the Christian tradition, we confess that God is a human being?

Perhaps it is because of that “terrific ending,” that the poet can always go on.