My friend and colleague, Christian Collins Winn (Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Bethel University) shares the following “dispatch” from the World Council of Churches assembly.

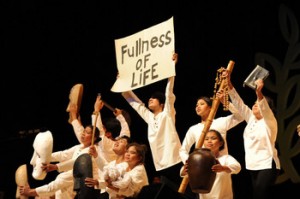

We are now in the middle of the 10th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, being held in Busan, South Korea, with the initial rush of feeling overwhelmed by the sheer diversity of linguistic, cultural and faith expression finally fading. This is my second Assembly—I attended the 8th Assembly in Harare—and I can say that, this time, I am no longer overwhelmed to the point of being unable to think. I can see clearly that Christian pluriformity is the norm of the world Christian movement.

There are many stories developing at the WCC Assembly. There is the response of the Churches to the convergence document, The Church: Towards a Common Vision issued in 2012 by the commission on Faith and Order. This document has been under  preparation since 1993 and is the second such document to come from Faith and Order since the publication of the seminal Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document published in 1982. There have been reflections on mission in light of the 2012 WCC statement Together Towards Life: Mission and Evangelism in Changing Landscapes, the second document developed by the WCC on mission, and one marked by dialogue with world Pentecostalism, the Roman Catholic Church, and the World Evangelical Alliance. There has also been some controversy over a speech given by Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, of the Moscow Patriarchate. In an address delivered on Friday, November 1, 2013, Hilarion noted that the ecumenical movement faced a serious crisis if it could not forge a common witness around issues like the sanctity of life, and the traditional understanding of marriage: “Are we able to bear this witness if we are so deeply divided in questions of moral teaching, which are as important for salvation as dogma?” The speech drew both praise and protest from the delegates, a fact that shows how diverse and divided, the world Christian family is in regard to these issues.

preparation since 1993 and is the second such document to come from Faith and Order since the publication of the seminal Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document published in 1982. There have been reflections on mission in light of the 2012 WCC statement Together Towards Life: Mission and Evangelism in Changing Landscapes, the second document developed by the WCC on mission, and one marked by dialogue with world Pentecostalism, the Roman Catholic Church, and the World Evangelical Alliance. There has also been some controversy over a speech given by Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, of the Moscow Patriarchate. In an address delivered on Friday, November 1, 2013, Hilarion noted that the ecumenical movement faced a serious crisis if it could not forge a common witness around issues like the sanctity of life, and the traditional understanding of marriage: “Are we able to bear this witness if we are so deeply divided in questions of moral teaching, which are as important for salvation as dogma?” The speech drew both praise and protest from the delegates, a fact that shows how diverse and divided, the world Christian family is in regard to these issues.

Perhaps one of the most interesting stories to develop at the assembly has been the participation of the Korean churches in the event. It is fair to say that this event marks a kind of end of the emergence of the significance of Korean Christianity for the world Christian movement. Without the hospitality, organizational work, and financial contribution, the assembly would not have taken place. A significant dimension of this engagement, however, has been the inclusion of more conservative Korean Christian churches. No doubt, there are certainly groups who have chosen not to attend, and there have been a handful of protestors demonstrating from time to time outside—accusing the WCC of perpetuating a single liberal theology, a claim that cannot be substantiated in light of the documents described above, nor in light of the vigorous debates that have occurred over theological and ethical issues in the business plenary sessions where delegates receive committee reports, etc.—but these groups must be considered an anomaly even among conservative Korean churches. This is because of the participation of churches like The Yoido Full Gospel Church, with its one million members, and the Myungsung Presbyterian Church, the largest Presbyterian Church in the world. These churches, both their leadership and members, have been very involved in the Assembly and in the politics of the ecumenical movement more recently. In fact, the senior pastor of Yoido, Pastor Young-hoon Lee, has been intimately involved in the ecumenical movement in South Korea, even serving as the chairman of the National Council of Churches of Korea.

This is a startling change, given the longstanding suspicion towards the ecumenical movement among more conservative Christian groups, including Pentecostals and evangelicals. It should, however, be interpreted as a change as much among Pentecostal and  evangelical groups as within the WCC itself. It is to be presumed that most North America evangelicals will simply not know what to think about this, since many of the key institutions of American evangelicalism were founded originally over-against the WCC, including Christianity Today, the NAE, and the WEA. In fact, in preparation for my attending this event, most people had no idea it was even happening (a fact that probably says as much about general antipathy towards the WCC as about widespread lack of knowledge of international affairs among many in the US). That changes are occurring on both sides should be seen as the proper fruit of ecumenical work, wherein different groups engage one another to find out what they really have in common and what really divides them. The new developments in world Christianity and the ecumenical movement—which are really not all that new anymore—should hopefully spell the end of the tired liberal/conservative binary whose explanatory power was always suspect, because now there are groups engaging one another in new ways and finding that they have more in common than not, but also recognizing that the visible unity we seek still awaits us in the future.

evangelical groups as within the WCC itself. It is to be presumed that most North America evangelicals will simply not know what to think about this, since many of the key institutions of American evangelicalism were founded originally over-against the WCC, including Christianity Today, the NAE, and the WEA. In fact, in preparation for my attending this event, most people had no idea it was even happening (a fact that probably says as much about general antipathy towards the WCC as about widespread lack of knowledge of international affairs among many in the US). That changes are occurring on both sides should be seen as the proper fruit of ecumenical work, wherein different groups engage one another to find out what they really have in common and what really divides them. The new developments in world Christianity and the ecumenical movement—which are really not all that new anymore—should hopefully spell the end of the tired liberal/conservative binary whose explanatory power was always suspect, because now there are groups engaging one another in new ways and finding that they have more in common than not, but also recognizing that the visible unity we seek still awaits us in the future.