The following is a guest post by Josh de Keijzer. Josh is a Ph.D. Candidate in Systematic Theology at Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN). He blogs regularly at http://endofgod.wordpress.com. You can find him on Twitter at @Yossmantweets

Dutch conductor Hans Vonk once said of Beethoven: His music is the truth and nothing but the truth. It is true that where language stops music continues to speak. It is a realm where the unsayable can still be expressed. As such, music is theology. Both music and theology seek to find expression to the mysteries of life, of suffering, of hope… of God. It is no wonder that when I write theology, I have to listen to music. Music helps me to grope for that truth that is just beyond my words, to grasp that creativity beyond my own limitation.

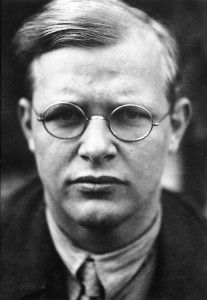

It was in such a creative moment, writing on the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer while listening to Felix Mendelssohn, that it suddenly

dawned on me: there is a link between these two. Analytical thought won’t get you there, but the music stirred something in me and my subconscious me reached out and got hold of a remarkable connection.

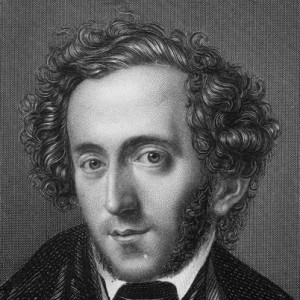

Bonhoeffer suddenly reminded me of Mendelssohn. Weren’t both prodigies who excelled beyond what was thought to be humanly possible? Mendelssohn performed and composed at an early age. Goethe compared him to Mozart. Bonhoeffer wrote his dissertation at the age of 21 and his habilitation 3 years later. They are both pieces of genius. Both died too early as well. Mendelssohn died from poor health at 38. Bonhoeffer was murdered by the nazis when he was 39. Both, while being reasonably successful, stood in the shadow of big contemporaries and only after their death did their work find the recognition it truly deserved. Mendelssohn had to deal with the likes of Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt whose progressive music made his conservative orientation pale in comparison. Bonhoeffer placed himself consciously and willingly in the sphere of the Barthian movement, which tried to retrieve a theological tradition that starts with revelation. Only in the 50s and 60s people started to recognize how important Bonhoeffer is as a theologian (and continues to be). As composer and theologian Mendelssohn and Bonhoeffer are geniuses in their own right.

Mendelssohn, a Jew from a family converted to Christianity, reworked Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress” into his “Reformation Symphony.” He also set in motion the rediscovery of the music of John Sebastian Bach, who had been long forgotten, by performing the St. Matthew Passion in 1829. Mendelssohn wrote: “To think that it took an actor and a Jew’s son to revive the greatest Christian music for the world!” Bonhoeffer for his part retrieved Luther’s thought not only for a renewal in theology; he also applied it in defense of the German Jews, especially those who were members of the church. He thought that where the church would no longer live in unity with the Jewish Christians in their midst, it ceased to be the church of Christ.

Lastly, both were musicians. One ended up incarnating theology into his music, while the other managed to infuse his theology with the eternal melody of the Incarnate. After all, not only is music theology, theology is music just as much.