Untold millions of women and girls around the globe are victims of physical and sexual violence. In the U.S. alone, over one million women suffer a physical assault by a partner. 25% of American women have been or will be victims of sexual assault. In many

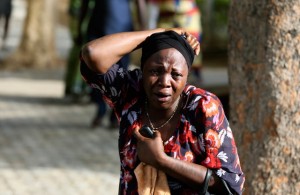

countries, structural and systemic violence against women results in even more horrifying statistics. How can we possibly wrap our minds around the violence committed towards women globally? The recent kidnappings of Nigerian girls by Boko Haram has raised to the surface a tragic reality that often goes unnoticed and unmentioned. What does the Christian church have to say to violence against women? And why is it that many Christian churches (and pastors) are part of the problem rather than part of the solution?

Elizabeth Gerhardt’s recent book, The Cross and Gendercide, addresses these questions. She argues that gendercide and other forms of violence, oppression, and exploitation of women and girls must be seen as more than a ‘women’s issue.” It most certainly a human rights issue, but one that calls for a theological analysis and response by the Christian church. She has put forth such an analysis and response in this important book, suggesting that the best way to understand violence against women is through a theology of the cross. She puts Luther and Bonhoeffer to work in helping us imagine how to face into this darkness. As she puts it,

A moral and ethical response from the Christian church is only a partial response. What is needed is a powerful, holistic and missional response rooted in a biblical theology of the cross because a theology of the cross does not separate proclamation of the gospel from the prophetic and active role of working to end injustice for millions of women and girls. (25)

The theological basis of social justice work matters, because it enables the church to thoughtfully respond, rather than simply react, to issues like gendercide (26). The starting point for this theological response, she rightfully points out, is the gospel. We must begin our reflection with God, who is both hidden and revealed in the suffering Christ, on the cross. For Gerhardt, “A theology of the cross is our lens for seeing more clearly the call God has for our lives and on our churches” (32).

Gerhardt provides Christians with a model for addressing social problems via a dialectic between the “two tasks of the church, kerygma and diakonia” [proclamation of the gospel and service] (80). In so doing, she offers a strong case for why social justice ought be divorced from theological reflection. But neither can theological reflection be done apart from the shadow side of humanity and the social ills and structural sins of our situation.

Gerhardt provides Christians with a model for addressing social problems via a dialectic between the “two tasks of the church, kerygma and diakonia” [proclamation of the gospel and service] (80). In so doing, she offers a strong case for why social justice ought be divorced from theological reflection. But neither can theological reflection be done apart from the shadow side of humanity and the social ills and structural sins of our situation.

Indeed, theology, when disconnected from reality, can itself add to social ills and become demonic. In chapter 3, where she unpacks the history of the “social, religious, and political roots of violence against women and girls,” she tells stories of actual resistance by pastors and other Christians to her own advocacy work for abused women. She writes,

I soon realized through my engagement with Christian churches that the very work of helping to empower and educate women with regard to their inherent dignity and right to life and safety was a threat to those that believed in a patriarchal system as a means to hold onto power. (66)

Theology can be either a means of oppression and injustice or a critique of injustice in the service of liberation and in proclamation of the gospel of Jesus. Reflecting on the Cross and Gendercide, it’s easy to see the better choice. I hope, in a subsequent post, to focus in more on Gerhardt’s particular framing of the “theology of the cross.”