What if what we define as “beauty” is specifically catered to our unique perspective alone? Whether it be just the compilation of our experiences archived in our memory that produce a resounding pattern of defining beauty, or, whether God intentionally crafted the beauty penetrations for our blueprint alone; beauty is truly in the eye of the beholder.

In the essay On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry perceives a similar idea— that beautiful objects have a way of seeming specially designed to fit with our experience. “It is though beautiful things have been placed here and there throughout the world to serve as small wake-up calls to perception, spurring lapsed alertness back to is most acute level.” We are drawn out by beautiful things, we cannot be passive to them, nor should we.

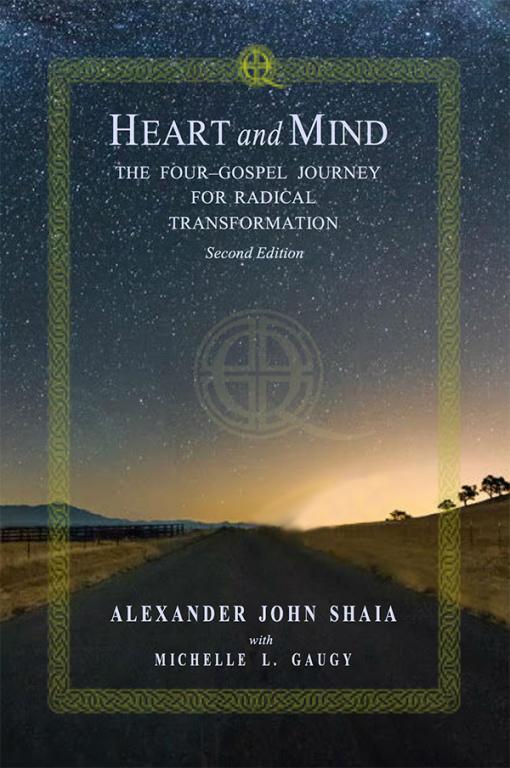

Scarry’s observation echoes a similar sentiment that Alexander Shaia expounds on in Heart and Mind: The Four-Gospel Journey for Radical Transformation. If you recall, in my last piece, Appreciative Beauty, I began to unfold what I had come to understand about Shaia’s essential practices of engaging the truths of beauty. In Heart and Mind, Shaia says that “nothing integrates and refreshes and brings us more deeply into our soul-work than the experience of beauty.” (379)

But what is beauty? How do we experience it? There are three levels, Shaia points out: “the appreciative, the collaborative, and the creative.” As I stated in my previous piece, what is objectively beautiful is not the focus, but how we see it and feel it, is.

Regarding aesthetics poetically, J.G. Hamann emphasizes the role that imagery plays. “The senses and the passions speak and understand nothing but images. Imagery comprises the entire treasure of human knowledge and happiness.”

What we feel internally, we then translate, using vivid language, yet failing to capture what it is we actually see. Just like the camera never does justice to the sun we watch setting; nor do our words capture the essence of the beauty that we notice, however we define it. So, we simply appreciate it.

We appreciate beauty internally first, from what we have already registered in previous experiences. Beauty is registered and then appreciated through our senses, and from there, Shaia writes, “to expand our experience, we also use our imagination.” (379)

Seek Beauty in Creation

Where do we find beauty? Do we have to travel to scenic mountain tops or secluded natural environments? Beauty is everywhere. Just stop for a moment and look. Philosopher and theologian Jeremy Begbie proposed that all of creation is beauty.

Creation’s beauty is not…something that lives in a land beyond the sensual or behind the material particular or beneath the surface, or wherever to which we must travel. Creation’s beauty is just that, the beauty of creation.

Interestingly, Shaia writes of collaborative beauty in a way that resonates. “The collaborative experience of beauty can be a bit more difficult to accomplish but is wonderfully rewarding. It is exactly as it sounds—the shared experience of beauty or even better, of beauty-making.” (380)

And what is beauty-making? It’s a creative experience. “To create means to bring forth something that has not existed before. It is a birthing—by definition, a holy activity. It is unique and wonderfully mysterious.” (380)

God’s Creation, spoken into existence from nothing, is the definitive example of beauty-making, and therefore, the creative experience of beauty.

The creative experience of beauty operates in an arena of expression. The Quadratos recommendation is that our journey includes “practices that engage the body because of their capacity to overcome the chatter of the ego-self, as well as more unity between mind, heart and body.” (380) Dancing, making music, singing, lovemaking— all ways in which we can collaborate with another and create a beauty experience to appreciate.

Using our bodies to create a beauty experience is a primal way that we can express and collaborate. In Poetic Theology: God and the Poetics of Everyday Life, William A. Dyrness notes:

We are becoming increasingly aware of the way our knowing, our feeling, and our aesthetic responses are impacted by our embodied nature. The deepest human experiences are not in spite of our bodies, but through them and in terms of them. (30)

Yes, our bodies can help us define what we perceive as an experience of beauty.

It is with the focus of using our bodies to express and create beauty that also supports the commitment that the Four-Gospel Journey of Radical Transformation asks of us. The importance of committing “to opening the deep well of the nonverbal aspect of ourselves.” Shaia continues, “Nonverbal creative work specifically engages the physical and the sensuous—and does so in a very direct way.”

Beauty is not so obvious to many of us. Sometimes it takes a moment for something of a beauty experience to envelope us. But when it does, surely you can recall, that it undoubtedly flows through your feelings and your senses in such a way that it leaves you in awe and wonder.

For many, living in a state of wonder equates to uncertainty, and for many, uncertainty is troublesome, if not threatening. We plot and plan out lives, scheduling appointments, recordings, vacations, 5-year, 10-year, 15-year goals. Wonder is a sentiment reserved for those who live carelessly. Or is it?

Robert Fuller, quoting Martha Naussbaum’s belief that “wonder is the only emotion that can lift the person above self-interest;” suggests that for success in and of religion, one “must ritualize experiences that provide a felt sense of this wider reality.” He concludes that, “A life shaped by wonder might…be the defining example of what ‘being spiritual’ means at its very best.” (Fuller, Wonder, p. 14,66)

This way of ritualizing experiences of wonder is part of Shaia’s recommendation for essential and continuing practices of engaging the truths of beauty.

Shaia concludes this portion with profound wisdom, that surely, he has undoubtedly come to obtain through his own challenging but rewarding Quadratos journey. It is necessary to quote this selection at length.

As we engage in regular creative work with image (or music or dance)—as we practice what we have learned and start to make it a part of our genuine and original new lives, our efforts move us further—into deeper encounter with the fourth path. There, we reap other benefits. Imagery moves easily in all directions, through the full spectrum of human experience. Images can be emotional, physical, intellectual, and spiritual. They can attract, repel, uplift, and horrify. They can be filled with tension or calm, be erotic or mundane. If in our creative work we stretch to experience and appreciate all of the sides within and around us, we will expand. (382)

Beauty and wonder are the regulators to the insanity and chaos that inundate our lives. If we are willing to pause for the presence— if we are willing to surrender to the scenes before us; we can escape the perils of negativity and the plaguing ills of the world. It will remind you that the beauty is there, within Creation, for you to behold, should you so choose.