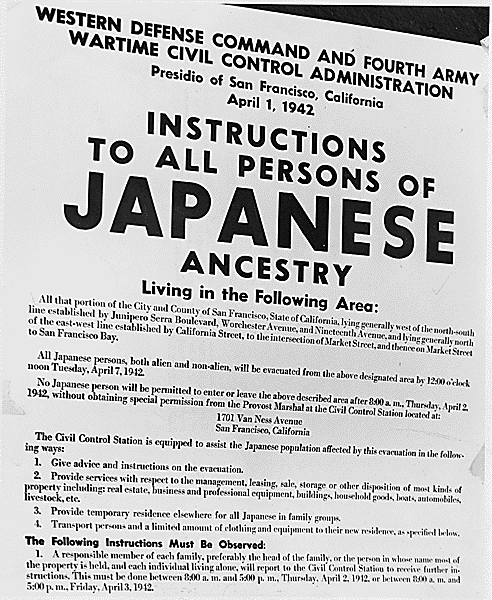

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

To my shame, on Monday I failed to note the anniversary of the brutal and unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan.

That attack killed 2403 Americans and wounded an additional 1178. It destroyed much of our Pacific fleet.

In the wake of “a date which will live in infamy,” Americans were understandably indignant, enraged, and terrified. They were especially afraid on the Pacific coast of the United States. There were rumors of impending Japanese naval attacks, and even, in the initial chaos and confusion, of Japanese divisions coming up through Mexico.

And then there were the nikkei, the Japanese immigrants and their descendants who lived especially in the western United States and Canada. Were they loyal? They spoke a different different language. Their culture was very foreign. Few of them were Christians. They looked very different. Foreign. Not like Us. Did they constitute a dangerous and subversive fifth column that could threaten and even kill Americans?

Growing up in southern California only a relatively few years after the end of World War II — it seemed ancient history when I was a kid, but, from my now much-lengthened historical perspective, I realize that it must surely still have been an acutely live memory for the adults around me — I knew a great many nisei and sansei (Japanese-Americans of the second and third generations in the United States) and their parents and grandparents. I knew people who had been interned, despite their United States citizenship and despite the fact that they had committed no crime whatever — relocated into camps in distant towns and states.

The people I knew were and are gentle people. They worked in construction. They owned and operated nurseries. They were in my elementary school classes and in my Boy Scout troop. Later, I came to know them as fellow members of the Church, as loyal embassy employees in foreign countries. I now know them as academic colleagues and in other roles.

(Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Click to enlarge.

Something on the order of 110,000 to 120,000 people were sent to camps in the interior of the United States, because other Americans decided that their loyalty couldn’t be guaranteed. (I’m leaving Canada out of this, although similar camps were populated with nikkei there.)

Many lost their jobs, their businesses, and their farms. Many lost much of their personal property. Some were even shot.

It was a shameful episode in American history.

As former Supreme Court justice Tom Clark wrote, “The truth is — as this deplorable experience proves — that constitutions and laws are not sufficient of themselves. . . . Despite the unequivocal language of the Constitution of the United States that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, and despite the Fifth Amendment’s command that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law, both of these constitutional safeguards were denied by military action under Executive Order 9066.“

Curiously, Italian-Americans and German-Americans were spared such treatment. That was, presumably, because they were Caucasians, and because their cultures were less foreign to the majority of Americans. It certainly wasn’t because Hitler and Mussolini weren’t our enemies.

Those who refuse to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.