My wife and I went to a viewing tonight for a young woman who died suddenly and unexpectedly a week ago last Sunday, at only twenty-two years of age. We didn’t know her, but we’ve known her father for many years and have sometimes worked on shared projects with him.

It was a melancholy evening. She had been full of life, a good daughter, with the confident expectation of many years ahead of her. Her death was — is — shocking.

I find myself thinking of two appropriately melancholy poems that impressed me already when I was a teenager and that have been favorites of mine over all the intervening years. I’m so fond of the two poets, in fact, that I’ve gone out of my way to visit the tomb of the first, in England, and the place on Bainbridge Island, in Washington State, where the second accidentally drowned. Neither poem fits this young woman’s story particularly well, but both attempt (as the Hamblin/Peterson column on Saturday also did) to say something, at least, about the death of young and promising people. It’s so unnatural, in a way. So very wrong.

(My student, thrown by a horse)

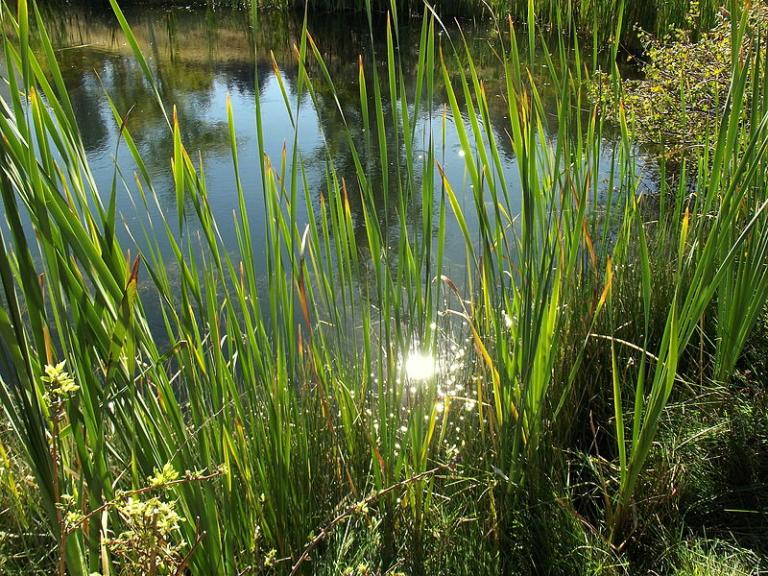

And her quick look, a sidelong pickerel smile;

And how, once startled into talk, the light syllables leaped for her,

And she balanced in the delight of her thought,

A wren, happy, tail into the wind,

Her song trembling the twigs and small branches.

The shade sang with her;

The leaves, their whispers turned to kissing,

And the mould sang in the bleached valleys under the rose.Oh, when she was sad, she cast herself down into such a pure depth,

Even a father could not find her:

Scraping her cheek against straw,

Stirring the clearest water.

My sparrow, you are not here,

Waiting like a fern, making a spiney shadow.

The sides of wet stones cannot console me,

Nor the moss, wound with the last light.

If only I could nudge you from this sleep,

My maimed darling, my skittery pigeon.

Over this damp grave I speak the words of my love:

I, with no rights in this matter,

Neither father nor lover.