Coming over from Holy Island, Lindisfarne, to Cumbria yesterday, we chose a slower road in order to visit Hadrian’s Wall — another area of Britain that I’ve long wanted to see but that, in more trips to the United Kingdom than I can count, extending over the better part of five decades, I never have.

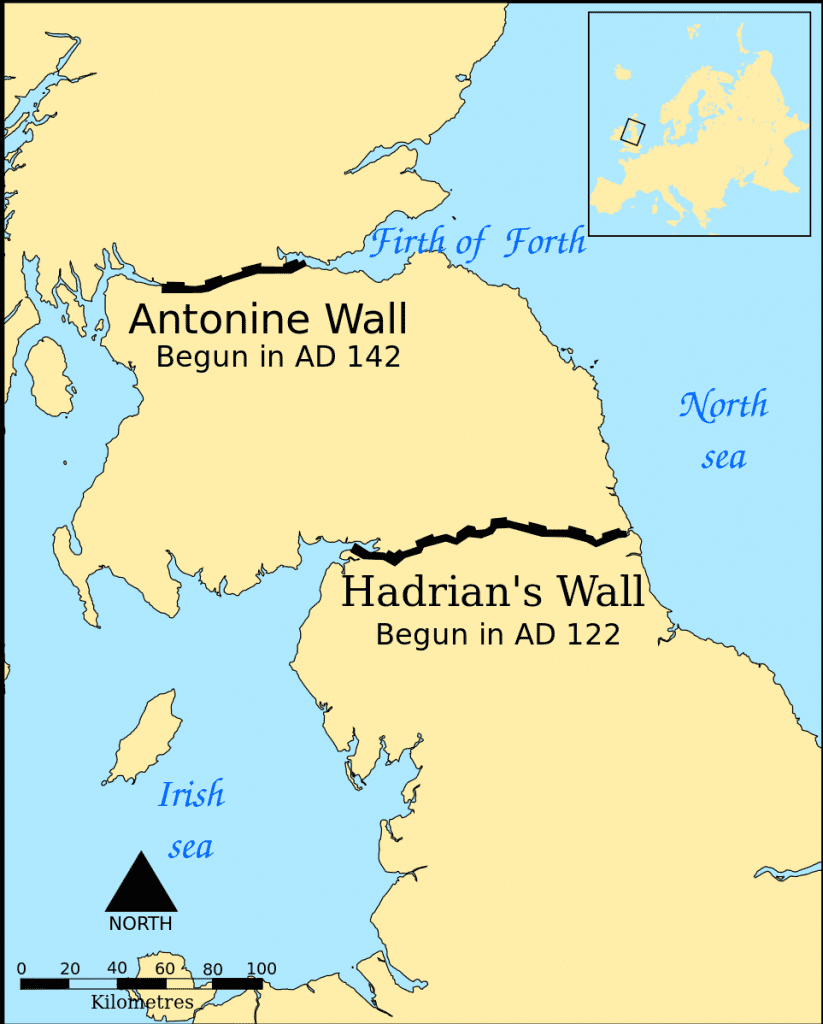

The Roman emperor Hadrian, who also left his indelible mark on Jerusalem (which he severely damaged during the Second Jewish Revolt, barring Jews from entering it and renaming it Aelia Capitolina) and in his famous villa outside of Rome, did a cost-benefit analysis and concluded that the price of conquering the entire island, including the potential expense of continued war, couldn’t be justified by the relatively low income to be derived from its poor, cold, savage, and underdeveloped northern parts. So he built a wall — across what one might term a “narrow neck of land” — in order to protect Roman Britain from the militant barbarians above it. (The presence of Roman civilization in what is now England is, of course, one of the principal reasons that England is distinct from Scotland to the north and from Wales — and Ireland — to the west. The pre-Roman Celts were pushed into those areas, remaining undomesticated and relatively un-Romanized.) Hadrian’s Wall marked the northern border of the Roman Empire.

The wall was originally something like fifteen feet high and several feet wide — most of it has long since been exploited over nearly two millennia to build roads and homes and churches and to enclose sheep pastures with solid stone fences — and it was studded with sizable forts and small garrisons at regular intervals.

We also dropped in to see the archaeological area at Vindolanda, but unfortunately didn’t have time to go in, and, before that, to visit the remains of the Mithraic temple at Carrawburgh (ancient Brocolitia). Mithraism, a faith that derived from Iran and that was especially popular among Roman soldiers, is a fascinating topic in and of itself.

Here’s some material from a classic old book by Franz Cumont called The Mysteries of Mithra:

“The heavens were divided into seven spheres, each of which was conjoined with a planet. A sort of ladder, composed of eight superimposed gates, the first seven of which were constructed of different metals, was the symbolic suggestion in the temples, of the road to be followed to reach the supreme region of the fixed stars. To pass from one story to the next, each time the wayfarer had to enter a gate guarded by an angel of Ormazd [or Ahura Mazda]. The initiates alone, to whom the appropriate formulas had been taught, knew how to appease these inexorable guardians.”

In other words, there were certain things that had to be done and said when one reached these barriers, in order to enter into the presence of the god, or to mark off each heaven from the one before it:

“As the soul traversed these different zones, it rid itself, as one would of garments, of the passions and faculties that it had received in its descent to the earth. [There is an idea of preexistence here, of course; the soul is just going back to where it came from.] It abandoned to the Moon its vital and nutritive energy, to Mercury its desires, to Venus its wicked appetites, to the Sun its intellectual capacities, to Mars its love of war, to Jupiter its ambitious dreams, to Saturn its inclinations. It was naked, stripped of every vice and every sensibility, when it penetrated the eighth heaven to enjoy there, as an essence supreme, and in the eternal light that bathed the gods, beatitude without end.”

“It was Mithra, the protector of truth, that presided over the judgment of the soul after its decease. It was he, the mediator, that served as a guide to his faithful ones in their courageous ascent to the empyrean; he was the celestial father that received them in his resplendent mansion, like children who had returned from a distant voyage.”

So it was fun to walk across a sheep paddock and into the remnants of an ancient Mithraeum, built by and for ancient Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian’s Wall.

The central “myth” of Mithraism involves the god Mithra’s victory over a bull, which symbolizes the triumph of the Sun and of life and light. A local man with whom we spoke says that this lingers on the names of taverns, inns, and public houses in the vicinity of Hadrian’s Wall. We didn’t get a chance to do a survey, of course, but he says that a disproportionate share of them are named with some variant of The Bull or The Sun.

Posted from Brockwood Hall, Cumbria, England