Modern science has made enormous progress.

But, sometimes, it’s wise to remember how limited we and our knowledge are. In even basic things.

Consider, for example, an insight offered by the Polish-born Franco-American mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot (1924-2010):

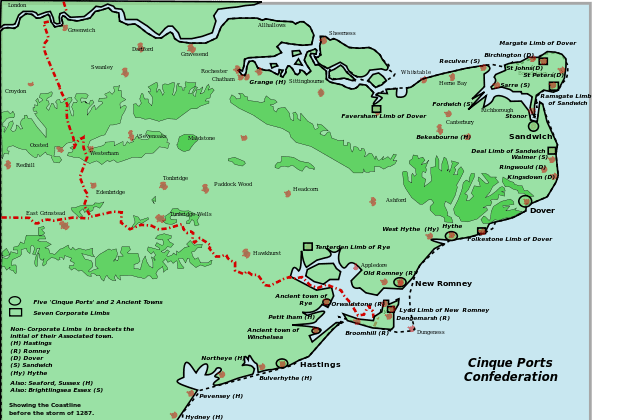

Using Great Britain as his specimen, Mandelbrot noted that the British coast becomes longer the more precisely we measure it.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Using a fairly crude measurement — say, as Britain might be viewed from a high-altitude aircraft or, even better, from a satellite in space — smaller bays and little rocky or sand peninsulas would be hidden. If one were to climb into a boat, though, and travel around Britain hugging the coast, even very small bays and promontories could be measured, and this would significantly alter one’s calculation.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

However, if you were to walk all around the British coast on foot, carefully registering and measuring even the smallest inlets and the most insignificant promontories, your number would be both more precise and larger.

As you decrease the size of your unit of measurement, you make your results more exact and, inevitably, discover more details and more irregularities.

And, theoretically, this can go on forever.

Even individual pieces of gravel and individual grains of sand manifest uncountable irregularities, and measuring even one of them would be a major undertaking, if not altogether impossible.

But we haven’t even reached the atomic level, to say nothing of the subatomic world of protons and neutrons and electrons and quarks.

With ever smaller standards of measurement, the length of the British coast would begin to approach infinity.

This is interesting and thought-provoking in itself, of course. But it can be applied in many other areas, as well.

If you read a one-volume history of the United States of America, for instance, there may or may not be any mention of John Tyler. Although he served from 1841 to 1845 as the tenth American president and was important in his day, he’s not regarded as especially important in the overall scheme of things. If you were to read a book about the presidents of the United States, though, you would learn considerably more. And if you were to pick up a biography of John Tyler, in particular — such biographies actually do exist — there would be a wealth of detail about him. (Did you know, for example, that, at his death in 1862, he was a loyal citizen of the Confederacy and a member of its newly elected House of Representatives? Or that, when he died, his coffin was draped, by order of Jefferson Davis, with a Confederate flag — thus making him the only American president thus far to be buried under a foreign banner?)

But you can always go into greater detail.

Suppose, for example, that you were determined to write an absolutely complete history of one hour in John Tyler’s life. Perhaps his lunch hour. An absolutely complete history would need to report on the position of the utensils on his table, what he was wearing, the number of grains of rice on his plate, the temperature of his room, the angle of the sun through his window, how thick the pane of glass was, how often his servants spoke to him, and on and on and on and on and endlessly on.

Plainly, this would be impossible, as well as impossibly dull.

We always think and narrate on a plane of considerable abstraction, omitting details that we regard as irrelevant or unimportant. History would be literally unattainable if we didn’t.

That things will be omitted from any historical account is inevitable — in principle as well as owing to the incompleteness of our sources. The only question is what should be omitted.

Consider another example: We might try to describe a simple thing like the emptying out of a room at the close of a sacrament meeting or a college class. It might be enough to say that there were 237 people in attendance, and that they mostly exited through two side doors at the back. If we tried to describe in detail the precise movements of each of those 234 people, that might well require years of careful work. And, even then, we would probably omit their sneezes, their acts of scratching their heads, waving, nodding, and so forth. To say nothing of the way dresses moved as their wearers walked, or of things much, much smaller than that.

In a very real sense, ordinary reality, like seacoasts and crowds, is essentially indescribable.